The 50 Best Horror Movies on Shudder (September 2025)

If you’re a horror geek, then surely you’re at least aware of the existence of Shudder at this point. The genre-focused service helped to prove the viability of niche streaming when it launched in 2016, boasting a robust library of horror, thriller and sci-fi features, while using its considerable marketing clout (thanks, AMC ownership) to ensure that it had far more visibility than would-be competitors. Along the way, it also explored the Netflix route of increasingly allocating budget toward original programming, bringing us series such as the Creepshow revival, and the resurrection of MonsterVision’s Joe Bob Briggs as a horror host. That has increasingly resulted in a lot of original horror movies on Shudder.

Today, the Shudder library is typically one of the more eclectic that can be found on the web, with more depth and unusual picks than any of the major streamers. It has grown and shrunk at different periods throughout the service’s lifespan, as Shudder has faced the same difficulties with streaming rights as everyone else, but currently boasts almost 600 titles—probably closer to 700 once you factor in the TV side of the equation—representing an interesting amalgam of vintage slashers, historical horror classics, modern releases, foreign films, hidden gems, and an ever-increasing number of originals. Certainly, Shudder is less reliant on straight-to-VOD junk than the likes of Netflix, which is a mark in its favor.

Allow us, then, to be your guide through the best Shudder has to offer.

You may also want to consult the following horror-centric lists:

The 100 best horror films of all time.

The 100 best vampire movies of all time.

The 50 best zombie movies of all time.

The 50 best movies about serial killers.

The 50 best slasher movies of all time

The 50 best ghost movies of all time.

The best horror movies streaming on Netflix.

The best horror movies streaming on Amazon Prime.

The best horror movies streaming on Hulu.

Here are the 50 best movies on Shudder:

50. What Josiah Saw

Year: 2022

Year: 2022

Director: Vincent Grashaw

Throughout Vincent Grashaw’s What Josiah Saw, what Josiah (Robert Patrick) saw remains the million dollar question. The gruff, menacing patriarch of a secluded Oklahoma farm, at first all Josiah sees are his waning crops and devout, childlike son Tommy (Scott Haze), whom he mercilessly taunts for believing in God. That is, until the night he wakes Tommy up, swearing he was visited by God. He explains that the Almighty told him that he and his children need to repent for their sins, as that is the only way to save the family’s matriarch, Miriam, from the eternal flame she was condemned to after she committed suicide two decades earlier. Okay—we’re 20 minutes in, and the answer already seems simple enough: Josiah saw God. He’s convinced of it, and the ever-earnest Tommy seems to be enthusiastically on board, too. But then we meet his other kids, twins Eli (Nick Stahl) and Mary (Kelli Garner). The former is engulfed in a life of crime and substance abuse, while the latter is clearly hiding a sinister secret—a suspicion that is confirmed when she reveals that, for some mysterious reason, she was sterilized when she was younger. The more Eli and Mary’s troubled lives are explored, the less likely it seems that what Josiah saw was simply God offering the family an opportunity to save Miriam’s soul. —Aurora Amidon

49. Bad Moon

Year: 1996

Year: 1996

Director: Eric Red

May we present what is arguably the most underrated werewolf movie of all time: Bad Moon. From the premise, which revolves around a single mom and her precocious little boy living out in the woods when their werewolf uncle comes to visit, you might for a moment think that this film will be treating its subject with kiddie gloves, but man would you be mistaken. This is made clear enough within the opening minutes, which not only includes a fairly explicit sex scene but then features a camp full of people being torn limb from limb by a werewolf before its head is blown off with a shotgun. It’s a fist-pumping, Peter Jackson-esque “FUCK, YEAH!” moment that sets the tone for what is a campy, stupid but very fun feature. In some sense, the actual main character is the family’s overgrown and defensive German shepard, who is the only one to suss out the werewolf’s identity, pitting dog vs. wolf in a battle of wits. Featuring a whole lot of bloodletting, Bad Moon is entertaining despite (or perhaps because of) its melodramatic performances, and it also happens to feature one of the best physical werewolf suits you’ll ever see. Why the filmmakers used any of the atrocious CGI you’ll see in the transformation scene is beyond me, given how spectacular the actual suit looks. Don’t sleep on Bad Moon–it’s the best werewolf movie you’ve never heard of. —Jim Vorel

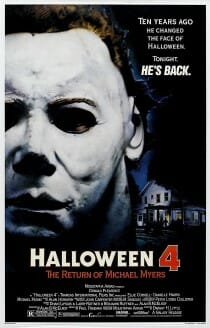

48. Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers

Year: 1988

Year: 1988

Director: Dwight H. Little

The return of Michael Myers to the franchise after Halloween 3: Season of the Witch’s misanthropic diversion into the anthology format was a move that initially pleased fans of the original Halloween, but the years that followed have not been kind to Halloween 4’s reputation. However, we are here to defend it: This is arguably a more entertaining film than first sequel Halloween 2, and one that gets an above-average horror movie performance out of Danielle Harris as Jamie Lloyd, who was only 9 years old at the time. Michael is at his menacing best, especially in the early dream sequence in which he emerges from beneath Jamie’s bed, and Donald Pleasence as Dr. Loomis is more histrionic and hyperbolic than ever as he insists—loudly and constantly—that Myers is a monster that must be destroyed once and for all. Halloween 4 is even blessed with one of the more legitimately shocking endings to an ’80s-era slasher film … but one that was unfortunately retconned at the beginning of Halloween 5 after producers got cold feet about committing to its consequences. In the end, that association with Halloween 5 (and don’t even get us started on Halloween 6) is the anchor around the neck of Halloween 4, but judged solely by its own merits, it deserves to be here. —Jim Vorel

47. WNUF Halloween Special

Year: 2013

Year: 2013

Director: Chris LaMartina

The success or failure of WNUF Halloween Special was always going to come down to how faithfully it could replicate the look and feel of a real local news broadcast from 1987, and in this respect it hits a home run. The cheap VHS video aesthetic and smarmy news anchors create just the right touch—schmaltzy, but in a way that is truly genuine rather than overtly parodic and over the top. Indeed, for the first 30 to 45 minutes of this film, it feels like a broadcast that could have truly happened. At the same time, that means this isn’t a horror comedy going for the jugular in terms of gags; the fake commercials for carpeting warehouses, tampons and children’s toys are exactly as funny as an average commercial from 1987 is to watch in 2017. Which is to say they’re going for wry smiles rather than huge punchlines, and it’s very well calculated. When the broadcast finally does fall apart into supernatural territory, it breaks the illusion somewhat to become a merely average found footage horror comedy, but it’s the normalcy preceding the bloodshedding that is oddly memorable. – Jim Vorel

46. Come True

Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director: Anthony Scott Burns

Come True, Anthony Scott Burns’ horror first, sci-fi second hybrid film essentially dramatizes what filmmaker Rodney Ascher gets at in his 2015 sleep paralysis documentary The Nightmare. What if your worst fears manifested in the real world? What if you couldn’t tell the difference between the land of the waking and the realm of the slumbering? What if the difference doesn’t even matter because, whether the nightmares are real or not, they still smother you and deny you rest, respite and sanity? Conceptually, the movie is frightening. In more practical terms it’s deeply unsettling, a terrific, sharply made exercise in layering one kind of dread on top of another. “Don’t you ever feel like you’re seeing something that you’re not supposed to?” Sarah (Julia Sarah Stone) asks Riff (Landon Liboiron), the scruffy Daniel Radcliffe stand-in conducting an ill-advised science experiment masquerading as a sleep study. The ever-present unnerving sensation that follows—that unspeakable terror is hovering over your shoulder—puts the film in close company with It Follows, another movie about disaffected youth on the run from evil they don’t understand and can’t fight. It’s contemporary, atmospheric and cuts deep—and more than that, it’s original. Burns conjures horror so vivid and tactile that at any time it feels like it might leap off of the screen and into our own imaginations or, worse, our own lives.—Andy Crump

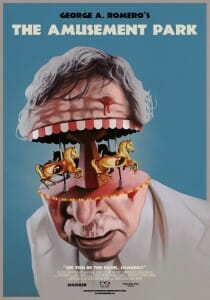

45. The Amusement Park

Year: 1973

Year: 1973

Director: George Romero

George Romero’s long-lost 1973 film The Amusement Park isn’t truly a narrative feature, instead being more like a disturbing PSA that was bizarrely commissioned by the Lutheran church as a way of highlighting the issues of ageism and elder abuse. Romero delivered exactly what was asked for, crafting a dreamy, surreal and disorienting tone poem about a man wandering an amusement park (a very thinly veiled metaphor for American society) as the uncaring forces around him steadily strip him of his dignity and then sanity. The completed film was apparently deemed too soul-draining for release, and it is quite effectively morose throughout, even if it lacks much in the way of modern commercial appeal. It’s not the most focused effort, but its 2021 release allows Romero to deliver one last blast of buckshot at American culture from beyond the grave. —Jim Vorel

44. Hush

Year: 2016

Year: 2016

Director: Mike Flanagan

Hush is a simple, intimate film at heart, and one that takes more than a few cues from Bryan Bertino’s The Strangers, among other home-invasion thrillers. Director Mike Flanagan, whose Oculus is one of the decade’s better, more underrated horror films, remains a promising voice in horror, although Hush plays things considerably safer than that ambitious haunted mirror tale did. Here, the gimmick is that the sole woman being menaced by a masked intruder outside her woodland home is in fact deaf and mute—i.e., she can’t hear him coming or call for help. At first, the film appears as if it will truly echo The Strangers and keep both the killer’s identity and motivations secretive, but those expectations are subverted surprisingly quickly. It all boils down into more or less exactly the type of cat-and-mouse game you would expect, but the film manages to elevate itself in a couple of ways. First is the performance of actress Kate Siegel as protagonist Maddie, who displays just the right level of both vulnerability and resolve, without making too many of the boneheaded slasher film character choices that encourage you to stand up and yell at the screen. Second is the tangible sense of physicality the film manages in its scenes of violence, which are satisfyingly visceral. Ultimately it’s the villain who may leave a little something to be desired at times, but Hush is at the very least a satisfying way to spend a night on the couch. —Jim Vorel

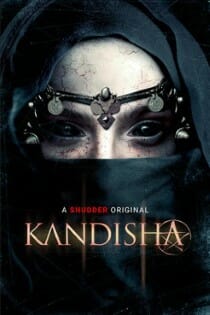

43. Kandisha

Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director: Julien Maury, Alexandre Bustillo

what the filmmakers achieve through their script and direction is a wickedly successful creature feature that highlights an underrepresented but widely-held fear among a considerable portion of France’s populace. The portrayal of Kandisha is incredibly layered and diverse, manifesting as mysterious, alluring and abjectly horrifying during different appearances. The viewer tandemly craves and dreads her arrival on-screen, which is an incredibly effective approach to keep the monster from losing its edge after multiple kills. The deaths are also cleverly fused with supernatural elements alongside the directors’ penchant for massive blood loss and bodily evisceration. When it comes to keeping the mounting body count compelling, Maury and Bustillo’s twisted creativity ensures each kill is brutal, both in terms of gore and toying with established emotional stakes. —Natalia Keogan

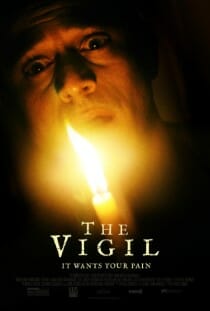

42. The Vigil Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director: Keith Thomas

Yakov (Dave Davis) has recently left the Hasidic Jew community after experiencing a trauma that dismantled his faith. He’s struggling to adapt to the outside world—particularly with money—and in the midst of this struggle, he’s approached to serve as a shomer, someone who watches over a body until it is buried. Typically a shomer is a family member, but in desperate circumstances, someone will be paid to serve this role. So Yakov takes up his post looking over the body of the deceased Mr. Litvak. But this isn’t going to be a night for easy money. As soon as Yakov settles in for his five-hour shift, strange things immediately start happening. He sees shadowy figures lurking in dark corners, he hears strange whispers and feels as if something is watching his every move. As the night progresses, he discovers that a mazzik, a type of demon, is haunting the home, its family and Yakov himself. It is feeding on them, using their grief and trauma to fuel its evil. Central to the power of The Vigil is Davis’ performance as Yakov, created by both Davis’ performance and Thomas’ writing. The film has a short and sweet runtime of 90 minutes, and with that short amount of time, Davis and Thomas are able to create a complex character that has gone through a life of both love and despair. Davis’ frustrated and sorrow-filled face tells a story of a man who just wants to live a life that is his own. Paired with those facial expressions, Thomas’ script quickly and effectively showcases both Yakov’s naivety in the world of technology and women—as he literally Googles “how to talk to women”—and his strength, as he prepares to face off with the mazzik. This is not a generic horror character that blends into the wallpaper, but someone worth cheering for until the credits roll. This is a story that, while following the expected story beats of possession films, still feels unique thanks to Thomas’ specificity and dedication to creating something lean and mean.—Mary Beth McAndrews

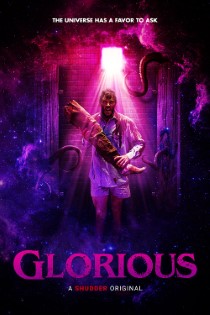

41. Glorious

Year: 2022

Year: 2022

Director: Rebekah McKendry

Glorious would completely fall apart were it left to an actor who was not up to the challenge, but Kwanten nails it. Given that he is only ever acting against a bathroom stall or his own reflection, it is impressive that he is able to carry the audience through the many emotional pivots Wes goes through in 79 minutes. We do not have a lot of time to get to know him before the tension escalates, and Kwanten’s performance makes sure we never miss a single beat of his suffering or frustration. Where Glorious stumbles a bit is in the mythology it hopes to create. From early on it is evident that there are greater forces at play, and whatever is talking to Wes is just easing him into the enormous world of its making. There are clear nods to Greek mythology and Lovecraft’s visions of the elder gods, but it feels more like a collage of random elements than the creation of a cohesive, reimagined mythology. Much like the graffiti on the bathroom walls, it is a collection of Easter eggs, not a single sweeping mythos. The allusions are fun to identify, but it feels like a missed opportunity to create a truly defined experience for Wes and this voice. Given its limited cast, location and budget, Glorious is an impressive feat. It never drags or feels more claustrophobic than intended. Thanks to strong performances and mostly tight writing, it’s a tense little chamber film, with deities and grand ideas, but without pants. —Deirdre Crimmins

40. Berberian Sound Studio

Year: 2012

Year: 2012

Director: Peter Strickland

Playing with reality and fantasy, the literal and the subconscious, Berberian Sound Studio will understandably be compared to the work of David Lynch. But even if it’s not as startlingly original as that director’s finest films, the movie does offer a quietly building sense of unease as we realize that something isn’t quite right about this recording studio. Maybe it’s the charlatans with whom Gilderoy has to work. Or maybe it’s something else, something inside this closed-off man that he’s never quite acknowledged before. Ultimately, Berberian Sound Studio may be yet another psychological character study about the ways in which life and art intersect. But when it’s this genuinely upsetting and confidently executed, who can resist one more trip through a house of mirrors? —Tim Grierson

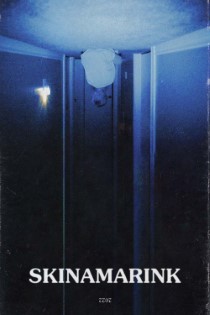

39. Skinamarink

Year: 2023

Year: 2023

Director: Kyle Edward Ball

This is a daring, unsettling, inscrutable and at times deeply boring venture into the farthest boundaries of horror esotericism, utterly unlike anything that most viewers will have ever seen before. If someone hosted a filmmaking competition where the stated goal was to engineer a work as divisive as it possibly could be, surely Skinamarink would be a shoo-in to win the grand prize. Created on a budget of $15,000 (Canadian!) as the feature debut of filmmaker Kyle Edward Ball, and dedicated to assistant director Joshua Bookhalter, who passed away during post-production, Skinamarink is an exercise in experimental, sensory-driven horror filmmaking. Now, when one says “sensory-driven” in this context, one might expect that to imply a certain lushness that overwhelms the senses, a la James Cameron’s approach in Avatar: The Way of Water. Skinamarink, however, is more like the opposite—the film’s ultra grainy visual aesthetic and muddy audio (with cleverly hardcoded subtitles) slowly but surely hypnotizes the viewer into a state of heightened suggestibility, until the viewer’s mind begins to provide its own hallucinatory meaning to what it is seeing. Ostensibly, Skinamarink is about a pair of siblings: four-year-old Kevin and six-year-old Kaylee. They live in an unassuming little house with their unseen father, with the status of Mom a veiled mystery that hints at pain and separation. One night, they awake to find that the house seems changed—doors and windows have disappeared, and any parental presence is missing. Objects are strewn around in seeming patterns, while a deep, gargling voice whispers from the darkness. “Oneiric” is the most perfect single word for the experience. Its images are like watching closed circuit security camera footage of someone’s mental projections during a fever dream. Its sounds recall things heard in the dead of the night from a childhood bedroom, and then blissfully forgotten by morning, only to be recalled in a moment of terror decades later. I look forward to watching the wider world discover Skinamarink, feeling for all purposes as if they’ve blundered into a parallel dimension. Like the titular child of The Twilight Zone’s “Little Girl Lost,” they’ll watch as a familiar place becomes a seeming prison, bound by dream logic, boundless and empty. I certainly won’t forget it.—Jim Vorel

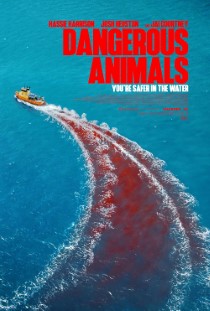

38. Dangerous Animals

Year: 2025

Year: 2025

Director: Sean Byrne

It’s fascinating and enlivening to watch how the fusion of two intensely familiar subgenres–serial killer thriller and shark-starring B-movie–can result in a work that is somehow brimming with life and verve. Like multiplying two negative numbers, the result (in this one instance, don’t get any copycat ideas) becomes positive, rendering buzzy Cannes survival horror flick Dangerous Animals as one of the summer’s most thrillingly visceral surprises. Anchored by a duet of extremely strong genre performances from final girl Hassie Harrison and especially the raw physicality of antagonist Jai Courtney–in a genuinely star-making turn–Dangerous Animals ascends to the top of this particular food chain, a glorified B-movie given appeal beyond its salacious premise through sharp filmmaking and even the occasionally lyrical aside. This is all so much better than “serial killer shark movie” has any right to be.

Nor is the film really any more than it promises: It eschews the need for narrative twists and relies on the elemental simplicity of its metaphor. Hunter vs. hunted. Fisherman vs. fish. Ideological mania vs. the pure determination to survive. We may lump it into the category of “shark movies,” which we’ve previously described as the lowliest of all horror subgenres, but in truth this is less genuinely an entry in that niche than something like 2016’s The Shallows, which represents the gold standard for modern shark films, perhaps the best in the half century since Spielberg’s Jaws launched the era of the summer blockbuster. Dangerous Animals is less purely “shark movie” and instead a tautly made serial killer psychological thriller, which just so happens to thematically weave itself around the grim outline of the ocean’s top predators. In truth, it revolves entirely around the considerably more viciously predatory nature of (male) human beings, as highlighted by a scintillating turn from its villain. —Jim Vorel

37. The Innkeepers

Year: 2011

Year: 2011

Director: Ti West

When you’re working in indie horror, a big part of success is learning how to turn your budgetary limitations into a positive–to rely less heavily on effects and setting and more on characterization and filmcraft. Ti West understands this better than most, which is part of what made his earlier House of the Devil so effective. The Inkeepers has some of the same DNA, but it’s rawer and more “real,” following the mostly unremarkable exploits of two friends as they work in a dingy old bed & breakfast and conduct nightly paranormal research in their place of business. They’re well-cast and feel like two of the most “real people” you’re likely to see in a horror film–West, feeling in moments like a horror Tarantino, enjoys lingering on them during their conversations and small-talk, which builds a sense of casual camaraderie present between long-time co-workers. Of course, things do eventually start going bump in the night, and the film ratchets up into a classically inflected ghost story. Some will accuse it of being slow, or of spending too much time dawdling with things that are unimportant, but that’s “mumblegore” for you. Ultimately, the reality imbued into the characters justifies the time it takes to give them characterization, and you still get some spooky “boo!” moments in the final third. It succeeds on the back of strong performances. —Jim Vorel

36. Stopmotion

Year: 2024

Year: 2024

Director: Robert Morgan

Folks on the prowl for monstrously uncanny thrillers need to prioritize Robert Morgan’s Stopmotion. The award-winning short filmmaker’s hallucinatory feature debut remarkably blends stop-motion with live-action like it’s a commonplace horror practice. Its themes stoke the harmful fires that entrap creative types who lose themselves in their projects, recalling the delicious instability of Prano Bailey-Bond’s delirious Censor or Peter Strickland’s sonically sinister Berberian Sound Studio. Morgan bleakly and ingeniously captures what it means to be a “tortured artist,” hybridizing an icky yet alluring stop-motion style that feels like a collaboration between claymation celebrity Lee Hardcastle and slasher legend Leatherface. —Matt Donato

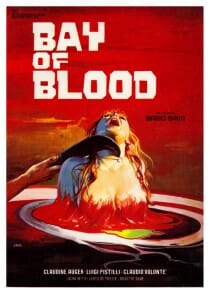

35. A Bay of Blood, a.k.a. Twitch of the Death Nerve

Year: 1971

Year: 1971

Director: Mario Bava

A Bay of Blood, released in the U.S. as Twitch of the Death Nerve, is the most important proto-slasher to often get left out of conversations on the history of the slasher genre, and this simply will not stand. Although many Italian giallos of the ̵]7;70s have slasher elements and pre-date the likes of Black Christmas and Halloween, none of them have kills that so directly seem like something out of a Friday the 13th movie. And indeed, that series borrows heavily from A Bay of Blood, especially Friday the 13th Part 2, which recreates two of Bava’s the death sequences almost exactly–most notably the bit where two lovers get impaled on a spear in mid-copulation. It’s Bava’s goriest film without a doubt, although not his most visually striking or narratively sensible, in terms of plot–all of the killings basically revolve around obtaining land ownership. That uneven nature and lack of compelling characters holds it back slightly, but when he’s throwing the red paint around, A Bay of Blood is enjoyably lurid. —Jim Vorel

34. In a Violent Nature

Year: 2024

Year: 2024

Director: Chris Nash

When In a Violent Nature’s boogeyman (Ry Barrett) rises to spill the blood of campers who’ve wandered into his wood, it doesn’t have the look or feel of a horror movie. The forest is serene, shot as if its lumbering antagonist was just another part of nature. With gorgeous bright greens and a commitment to fully viewing its muddy, ragged creature design, In a Violent Nature isn’t hiding anything. Confident, imposing, bright daylight photography is more concerned with establishing an unassuming setting. We trudge past the inherently uncanny human rot lost out in the woods: A gutted shed, a burned tower, a rusted-out car. All the while, the killer lurches along, the camera at his back, in quiet pursuit of those unlucky enough to have disturbed him. And I do mean quiet—there’s only diegetic music in this film, adding tremendously to its methodical atmosphere. The daylight stuff is so imposing and confident that, when it flows into night, the fading visibility is so organic that it sneaks up on you. That’s not to say Nash and team try to take advantage of us in the dark. Some of the best, inventive and juicy kills come bright and early. The gruesome, delightfully disgusting kills are as nonchalant as they’d be for this creature—even the most elaborate and ridiculous (and they do get elaborate and ridiculous) play like he’s working through a set of crunches. And boy, do folks get crunched. —Jacob Oller

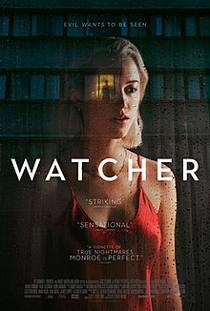

33. Watcher

Year: 2022

Year: 2022

Director: Chloe Okuno

Maika Monroe knows better than almost any actor working today how to turn her head or widen her eyes in mounting horror. The control she has over her body, the ability she has to convey realistic fear and her 2014 double-header of The Guest and It Follows made her an instant household name for genre fans. Perhaps one of those was director Chloe Okuno, who knows exactly what to do with her star in her paranoid debut feature (which follows her V/H/S/94 segment from last year), Watcher. A straightforward little B-treat, Monroe’s furtive glances out her Rear Window morph Watcher into a moody thriller elevated by its acting. Monroe plays Julia, a beautiful young housewife cooped up in an empty apartment and cooped up in an intimidating and isolating Bucharest after moving there with her husband Francis (Karl Glusman) for his work. Francis speaks Romanian. He entertains clients, makes friends, grabs drinks, chastises fresh cab drivers and translates day-to-day interactions with neighbors and landlords. Julia has none of that. No job, no friends, no real way to communicate with the world aside from her baser senses. She has her taped language lessons, which soundtrack her wistful wanderings around her lovely pale apartment and its massive window. Through that window, she sees those marking the building across the way. And one of them contains a figure that also stands at the glass, looking right back. —Jacob Oller

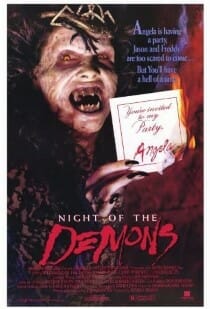

32. Night of the Demons

Year: 1988

Year: 1988

Director: Kevin S. Tenney

Night of the Demons is one of the most purely enjoyable entries in the late ’80s horror subgenre of “a bunch of young people go to a spooky location and all wind up dead,” which arguably reached its zenith a year earlier in Evil Dead 2. Make no mistake, this film can’t compete with the slap-sticky wit of early Sam Raimi, nor are any of its performers a Bruce Campbell quip machine in the making, but Night of the Demons makes up for it with shameless raunchiness and a generally gleeful attitude toward the demise of its characters. These guys are broad, amusing pastiches of different archetypes in 1980s youth culture, in much the same way as the teens from Return of the Living Dead, right down to the presence of Linnea Quigley. Yes, she’s naked here, although it’s at least not for the majority of the film, as in ROTLD. Instead, come for the top-notch makeup effects and the sick, sophomoric sense of humor. This one makes for perfectly appropriate Halloween-season viewing, as its “let’s get together in a haunted house for a Halloween party” premise is just begging for a cadre of demons to run amok. And so they do, with gory aplomb. —Jim Vorel

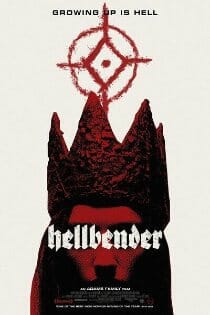

31. Hellbender

Year: 2022

Year: 2022

Director: John Adams, Zelda Adams, Toby Poser

Over the course of their eight-year collective filmmaking practice, the Adams family have continuously honed their aesthetic and narrative interests as artists. With Hellbender, the sixth feature from the nuclear family of filmmakers, confidence and creativity converge to produce something that feels like an alchemic breakthrough. Particularly following their 2020 supernatural thriller The Deeper You Dig, it appears the Adams have acquired a penchant for horror—a perfect complement to their signature low-budget, home-grown style. Though Hellbender utilizes many recurring motifs present in the Adams family’s work—such as dysfunctional family dynamics and nods to John Adams’ former career as a punk musician—it is certainly the most (literally) fleshed-out project the family has undertaken to date. 16-year-old Izzy (Zelda Adams, the youngest daughter and fellow co-director of John Adams and Toby Poser) has been warned from a young age by her mother (Poser) that the outside world will cause her nothing but harm due to her rare autoimmune disease. As such, Izzy spends her days frustrated and friendless, with only the vast landscape surrounding her mother’s reclusive mountain home providing her with any semblance of personal enrichment. Despite being forbidden to leave the property, Zelda’s relationship with her mother is far from acrimonious—they are playfully affectionate with one another, cradling each other’s faces in their hands and venturing into the verdant forest for rainy day hikes. They even perform in a drum and bass punk rock band, appropriately named Hellbender, donning audacious face make-up and practicing tight, catchy songs for the sole benefit of themselves. Every facet of Hellbender has the intrinsically magical quality of being hand-helmed by a small faction of creatives that execute every stage necessary for the film’s production. The cinematography by Zelda and John is just as impressive as the laid-back yet quirky costume design by Poser. The end result is completely stunning in its scope, tandemly laser-focused on two individuals and their insular livelihood while exploring the vast terror of supernatural possession. By the time the film come to a gory, gloomy conclusion, the viewer walks away feeling thoroughly put through the wringer—inherited traumas, overbearing impositions and brooding bloodlust are never presented in a completely straightforward fashion, providing ample twists to accompany any revelation the film wishes to divulge. Tethered closely to the emotions and artistic sensibilities of the tight-knit family that created it, Hellbender is a can’t-miss foray into folk horror. Unabashedly creepy yet perplexingly comforting, it will inevitably remind audiences of the most eccentric aspects of our upbringings. At the same time, it will evoke deeply-concealed memories of the anguish of undergoing growing pains—a veritable hell on Earth if there ever was one.—Natalia Keogan

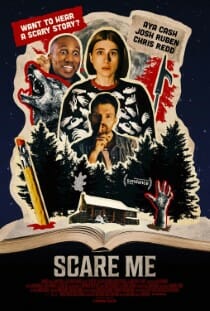

30. Scare Me

Year: 2020

Year: 2020

Director: Josh Ruben

For many, scary movies are fun. Watching scary movies is fun. Boil that down further: Telling scary stories is fun, no matter the setting, as long as you’re in proper company. Shudder’s Scare Me toasts that dynamic via a contest of wills between two horror authors trying to out-terrify each other before the second-best possible stage for telling scary stories: a crackling fireplace. (The very best is a campfire, but beggars can’t be choosers.) The authors are Fred (Josh Ruben) and Fanny (Aya Cash). Fanny is the best-selling writer behind the popular critical smash Venus, a zombie novel that, based on what little the audience hears about it, sounds like elevated horror nonsense (which is exactly the kind of thing that scored points on screens and shelves in the mid-2010s horror boom). Josh is a loser. He hasn’t written a damn thing or a thing worth a damn, and he’s secluded himself in a cabin at a Catskills resort to do Serious Work, which he doesn’t, because again, he’s a loser. Fanny’s staying in a nearby cabin, and when the power goes out across the area, she walks in on Fred and challenges him to scare her with his best shot.

The pace of Scare Me slows a tad more than ideal as Ruben takes the plot to its inevitable conclusion, but it’s still a joyful, satisfyingly eerie experience. There are reasons we enjoy the adrenaline blast horror movies give us. Scare Me, which should be essential viewing each Halloween season, understands those reasons well and celebrates them with enough laughs and gasps to leave viewers choking.—Andy Crump

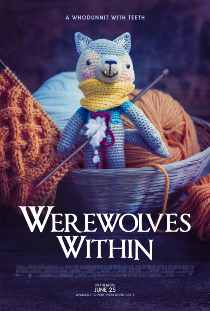

29. Werewolves Within

Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director: Josh Ruben

With the release of his feature film debut Scare Me last year, director Josh Ruben put himself on the horror-comedy map with his tale about horror writers telling scary stories. With Werewolves Within, Ruben further proves his skills as a director who knows how to walk that delicate line between horror and comedy, deftly moving between genres to create something that isn’t just scary, but genuinely hilarious. The cherry on top? This is a videogame adaptation. Werewolves Within is based on the Ubisoft game of the same name where players try to determine who is the werewolf; Mafia but with shapeshifting lycanthropes. Unlike the game, which takes place in a medieval town, Ruben’s film instead takes place in the present day in the small town of Beaverfield. Forest ranger Finn (Sam Richardson) moves to Beaverfield on assignment after a gas pipeline has been proposed to run through the town. But as the snow starts to fall and the sun sets behind the trees, something big and hairy begins hunting the townsfolk. Trapped in the local bed and breakfast, it’s up to Finn and postal worker Cecily (Milana Vayntrub) to try to find out who is picking people off one by one. But as red herrings fly across the screen like a dolphin show at the local aquarium, it feels almost impossible. Just when you think you’ve guessed the killer, something completely uproots your theories. Writer Mishna Wolff takes the core idea (a hidden werewolf in a small town where everyone knows each other), and places it in an even more outlandish and contemporary context to pack an even funnier punch. While the jokes never stop flowing in Werewolves Within, Ruben and Wolff never lose sight of the film’s horrific aspects through plenty of gore, tense scares and one hell of a climax. This film full of over-the-top characters, ridiculous hijinks and more red herrings than you can keep track of is a great entry in the woefully small werewolf subgenre.—Mary Beth McAndrews

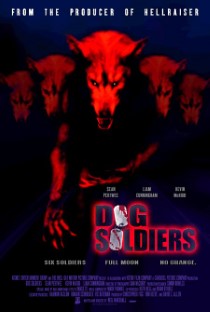

28. Dog Soldiers Year: 2002

Year: 2002

Director: Neil Marshall

If someone ever asks me to venture an opinion on the best-looking practical effects/full-body werewolf suits used in a feature-length horror film, the choice of Dog Soldiers will be an easy one to make. This isn’t exactly a character-driven tale, a la American Werewolf in London, but instead an action-packed wolf yarn that pits a squad of soldiers against a rampaging family of lycanthropes in the Scottish Highlands. It borrows the basic structure of Night of the Living Dead to do so, having our group of protagonists holed up in a rickety farmhouse that is under siege by a large group of werewolves. As members of the squad are slowly picked off in increasingly grisly ways, the only question is who, if anyone, will survive. Dog Soldiers is a stylish (although sometimes a bit dark and hard to see) entry in the genre, with great pieces of action and, as previously mentioned, some really spectacular werewolf designs. I love the odd proportions they give the monsters—humanoid bodies with long, somewhat thin limbs which give the werewolves an imposing height, but heads that are straight-up wolves rather than a mixture of wolf and man. They look utterly alien, and it’s great.—Jim Vorel

27. The Boy Behind the Door

Year: 2021

Year: 2021

Director: David Charbonier, Justin Powell

The thing The Boy Behind the Door relies on the most is not nostalgia, though if you’re an adult, it may feel that way. The power of friendship is what keeps the heart of this film pumping fresh blood until the very end. There is something so sweet and unbreakable about a true childhood kinship, and that treasured bond is ripe between Bobby and Kevin. They are each other’s rock, and their dialogue and character impulses solidify this important piece of the puzzle that aids them throughout. Their mantra, “friends till the end,” sustains them through their trials and tribulations, and it is beyond clear that their symbiotic connection is their greatest asset. It’s easy, as a viewer, to feel deep catharsis with this element and your mind will wander back to those idyllic childhood moments with whomever was your best bud. But it seems the filmmakers also made it a point to take those feelings a step further: Their story makes you so thankful for those times, amid the uncertainty of life and the insidiousness of humanity, that the feeling will unsettle you. And, like The Boy Behind the Door, it should. —Lex Briscuso

26. The Others

Year: 2001

Year: 2001

Director: Alejandro Amenábar

The Others is a stately ghost thriller that is classical in structure, sumptuous in appearance and somewhat familiar in its plotting. Borrowing heavily from the modus operandi of gothic horror literature and Hammer horror productions of the ’60s, it’s hard not to look at Nicole Kidman here and see her as doing an impersonation of Deborah Kerr in The Innocents, except playing a mother rather than “governess.” Still, The Others takes the bones of that kind of story, in the mold of The Turn of the Screw and adds a few more modern layers—an absent husband who mysteriously returns; a pair of servants who seem to know more than they let on; a few genuinely creepy scenes involving the children. It was rightly praised upon release as a stylish throwback in an era that was considerably more dominated by monsters and slashers, and its period piece setting gives it a certain timeless quality, 20 years later. The best ghost stories age well, and The Others is doing exactly that. —Jim Vorel

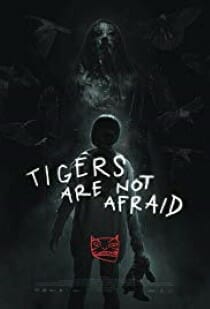

25. Tigers Are Not Afraid

Year: 2019

Year: 2019

Director: Issa López

It’s possible, even probable, that a portion of Tigers Are Not Afraid’s audience will receive the film as a parable about the current humanitarian crisis unfolding along the U.S.-Mexico border, a clarion call for compassion and decisive legislation to put an end to the suffering inflicted on innocent families fleeing mortal peril and economic repression. Such is the myth of America’s legacy. But Issa López made Tigers Are Not Afraid years ago, before the administration in power escalated the United States’ already appalling immigration policies into full-on decimation. This is not a cry for action. It’s a snapshot of Mexico’s recent history that bleeds into its present day. Tigers Are Not Afraid molds the sickening consequences of cartel violence on Mexico’s children to fit the shape of folkloric narrative. It’s a fairy tale, and a horror film, though the two tend to go hand-in-hand: Fairy tales point us to the darkness that exists on society’s periphery—or, in this case, occupies society’s center. The world of Tigers Are Not Afraid is made of crumbling walls and whispers, a land of ghosts where children are acclimated to ducking for cover under their desks when bullets interrupt class time. (Another thread to tempt viewers toward forced topical readings.) All the world is horror even before López starts ushering ghosts into the fray.

Estrella (Paola Lara) is one orphan among many in the unnamed border town López has chosen as the film’s location. When she’s given three wishes by her teacher, she immediately asks for her mother to return. Her mother does—but the conditions of her return are fuzzy, so mom resurrects as a hoarse, desiccated revenant. On the opposite end of the spectrum is Shine (Juan Ramón López), also an orphan, but one devoted to keeping his fellow orphaned boys safe on the streets as they outmaneuver cartel thugs and perhaps hope to find justice against them. Estrella and Shine share the screen as sun and moon share the sky, casting the film with light and darkness amidst graffiti-streaked buildings, the threat of death lurking in alleyways and on street corners. With Tigers Are Not Afraid, López threads the needle through tragedy and hope. This is at once a grim movie, an optimistic movie and a redemptive movie. It’s a welcome reminder that fairy tales and folklore are an essential part of our culture, too. At the most inhuman times, they lay down a path back to humanity. —Andy Crump

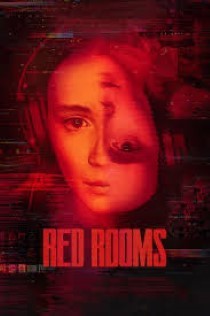

24. Red Rooms

Year: 2024

Year: 2024

Director: Pascal Plante

Red Rooms is a movie fixated on a single performance, itself fixated on a serial killer. The performance is that of Juliette Gariépy, fantastic as the unblinking Kelly-Anne. The serial killer is the Gollum-like and dead-eyed Ludovic Chevalier (Maxwell McCabe-Lokos), accused of butchering three young girls live on a pay-per-view stream. This dark web snuff stream is a Red Room, and it’s unclear what aspect of the case Kelly-Anne is obsessed with as she stares intently in the background of the film’s gripping courtroom scenes. Is she another romanticizing rubbernecker here to ogle real deaths as true-crime entertainment? Or is it darker? Is she—like her trial-observing counterpart Clémentine (Laurie Babin, excelling at a more emotive, girlish foil)—a hybristophilic fangirl, a prison groupie who’d send a love letter to Ted Bundy?

These questions, and the complexity that lies underneath, drive Red Rooms beyond the effectively daunting way writer/director Pascal Plante reveals the details of the central crimes. And, without ever showing too much, Plante has crafted one hell of a stomachache. He doesn’t show, and he barely tells. The little we do glean only adds to the dreadful realism. Less than two hours, yet feeling like an eternity thanks to some well-planned and executed long takes (featuring some particularly engaging monologues from Natalie Tannous, playing the prosecutor), Red Rooms traps us in the mindset of its intense lead as we get ever more involved with the case. —Jacob Oller

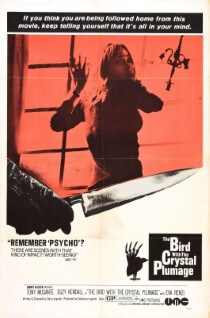

23. The Bird With the Crystal Plumage

Year: 1970

Year: 1970

Director: Dario Argento

Dario Argento came out swinging with this giallo debut, grabbing you by the throat with its opening kill that traps our writer protagonist in huge glass sliding doors, helplessly watching a killer murder a woman in an art gallery. It didn’t just announce Argento’s talent for balancing panicked chaos with urgent, efficient suspense craft, it set up a recurring motif in his filmography: Being the unwilling eyes of some violent, invasive voyeurism. What follows is a robust, dexterous mystery that keeps finding new ways to hook the audience, setting the standard for giallo iconography—a black gloved killer, haunting, anonymous phone calls—in the process. —Rory Doherty

22. The House of the Devil

Year: 2009

Year: 2009

Director: Ti West

Detractors complain that Ti West’s movies are “slow,” which is missing the point. A better adjective is “deliberate.” On The House of the Devil, the first film to really start giving him a reputation as a director to watch, West builds the tension gradually and carefully, as though there is nothing scarier than watching a young woman dance around an empty house while listening to the Fixx. By the time the second act ends, you’ve been holding your breath for an hour when the film explodes into its gory, violent third act, which offers a perverse sense of release. It also gives Jocelin Donahue’s heroine her finest moment, as she at least attempts what the audience is by then shouting for her to do. It’s another film where the low-budget look perfectly fits the aesthetic, mirroring the style of “old dark house” and Satanist films that West is clearly drawing on as inspiration. —Stephen M. Deusner

21. Pontypool

Year: 2008

Director: Bruce McDonald

Pontypool is one of the most cerebral and ethereal re-imaginings of what the word “zombie” might be taken to mean, and it’s a film that I respect immensely for taking the hard road. Zombie fans (and horror fans in general) are a fickle bunch–we want things we haven’t seen before, but we also want our films to reflect everything in the history of the genre, which is a near-impossible task. Pontypool doesn’t bother at all with zombie convention. Rather, its antagonists, which are never called “zombies” and are occasionally referred to as “conversationalists” by director Bruce McDonald, are a criticism of 21st century humanity’s inability to truly connect and discuss pertinent, truly significant issues. There is indeed a “zombie virus” here, but it’s not transmitted through bites or blood, but by ideas, by the very English language, which has become so watered down with pleasantries and insincerity that it’s taken on a destructive life of its own. The film ultimately contains all of the gore and violence you would expect from a great indie zombie film, simply delivered in a unique way, with a distinctly new message. It’s a truly postmodern zombie film and deeply dissatisfied jab at society itself. —Jim Vorel

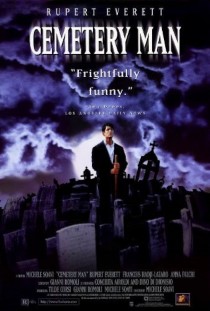

20. Cemetery Man

Year: 1994

Year: 1994

Director: Michele Soavi

Zombies, and really the horror genre in general, went through something of a lull in the 1990s, outside of genre-savvy offerings such as Scream. In Europe, though, unconventional zombie films did still pop up now and then, of which Cemetery Man is the most notable. The premise itself sounds old-school and spooky: A cemetery caretaker lives with his Igor-like assistant and kills the zombies that occasionally rise from their graves after being buried for 7 days. In reality, though, the film is essentially a horror art-comedy, an experimental and partially plotless, dreamy movie about the protagonist drifting through life without purpose and questioning why he bothers carrying out his duty. He pines after a woman who he immediately loses to zombification, and there are elements that almost remind one of American Psycho in the hopelessness and lack of identity he faces–even when the protagonist tries to commit atrocities and get caught, nobody seems to notice or care. It has the artistic flair and painterly quality of the earlier Italian films on this list, while incorporating some of the humor one might find in Re-Animator, but it’s moodier and more taciturn. It’s a film that tries to do many things at once, and is worth watching if only to shake your head considering the versatility of zombies, from simple flesh-eaters to complex symbols of entropy and nihilism. —Jim Vorel

19. Black Sunday

Year: 1960

Year: 1960

Director: Mario Bava

After years spent toiling as a cinematographer and (at times uncredited) co-director on an assortment of moderate to low-budget horror and sword-and-sandals productions, Mario Bava broke out in a big way with Black Sunday. Loosely (and I mean loosely) based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol, the film centers on the resurrection of a 17th century vampire-witch (Barbara Steele) and her paramour (Arturo Dominici) as they seek revenge on the descendants of the brother who executed her. Designed as a throwback to the Universal Monster movies of the 1930s, Black Sunday drew significant controversy for several gruesome sequences (including, but not limited to, the implementation of a spiked death mask and a moment where a cross is stabbed through an eye). Naturally, this kind of notoriety only intensified the film’s popularity. Though time has since lessened the impact of the gorier scenes, the movie still packs a huge punch with its nightmarish atmosphere, which is further accentuated by its vivid black-and-white photography and striking production design. An influence on filmmakers from Tim Burton to Francis Ford Coppola, Black Sunday remains a towering beast in the history of the horror genre. —Mark Rozeman

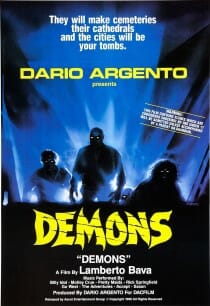

18. Demons

Year: 1985

Year: 1985

Director: Lamberto Bava

Demons is the best zombie film ever made that entirely pretends to be about a different type of monster. Because, let’s be clear, the creatures in Demons are 100 percent zombies, and it’s a near-perfect example of a “zombie movie”—there might be no other film on this list that is closer to the structure of Night of the Living Dead than Demons. The action all takes place in an opulent old movie palace, the perfect location to bring together a large cast of weirdo characters—from preppy kids to arguing lovers, a pimp with his prostitutes and even a blind man who is simply listening to the film. Unfortunately, they all fall prey to an outside plot, as mysterious forces have orchestrated both the showing of a shocking horror film and the outbreak of a plague of zombification/demonization among the people in the audience. What follows is a meat grinder of ’80s practical effects violence and survival, as the audience members still alive barricade themselves into the balcony and attempt to mount an escape. The story is as simple as it gets, but the outstanding zombie/gore effects, corny characters and “who will survive?” mystery propel it to classic status. Plus, you’ve got to love a horror movie that suggests you might get killed simply because you attended a horror movie. —Jim Vorel

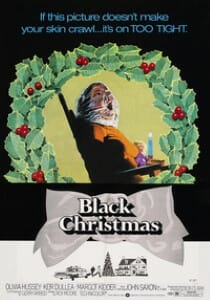

17. Black Christmas

Year: 1974

Year: 1974

Director: Bob Clark

Fun fact: Nine years before he directed holiday classic A Christmas Story, Bob Clark created the first true, unassailable “slasher movie” in Black Christmas. Yes, the same person who gave TBS its annual Christmas Eve marathon fodder was also responsible for the first major cinematic application of the phrase “The calls are coming from inside the house!” Black Christmas, which was insipidly remade in 2006, predates John Carpenter’s Halloween by four years and features many of the same elements, especially visually. Like Halloween, it lingers heavily on POV shots from the killer’s eyes as he prowls through a dimly lit sorority house and spies on his future victims. As the mentally deranged killer calls the house and engages in obscene phone calls with the female residents, one can’t help but also be reminded of the scene in Carpenter’s film where Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) calls her friend Lynda, only to hear her strangled with the telephone cord. Black Christmas is also instrumental, and practically archetypal, in solidifying the slasher trope of the so-called “final girl.” Jessica Bradford (Olivia Hussey) is actually among the better-realized of these final girls in the history of the genre, a remarkably strong and resourceful young woman who can take care of herself in both her relationships and deadly scenarios. It’s questionable how many subsequent slashers have been able to create protagonists who are such a believable combination of capable and realistic. —Jim Vorel

16. Mandy

Year: 2018

Year: 2018

Director: Panos Cosmatos

More than an hour in, the film’s title appears, growing lichen-like, sinister and near-illegible, as all great metal album covers are. The name and title card—Mandy—immediately follows a scene in which our hero forges his own Excalibur, a glistening, deformed axe adorned with pointy and vaguely erotic edges and appurtenances, the stuff of H.R. Giger’s wettest dreams. Though Red (Nicolas Cage) could use, and pretty much does use, any weapon at hand to avenge the brutal murder of his titular love (Andrea Riseborough), he still crafts that beautiful abomination as ritual, infusing his quest for revenge with dark talismanic magic, compelled by Bakshi-esque visions of Mandy to do her bidding on the corporeal plane. He relishes the ceremony and succumbs to the rage that will push him to some intensely extreme ends. We know almost nothing about his past before he met Mandy, but we can tell he knows his way around a blunt, deadly object. So begins Red’s unhinged murder spree, phantasmagoric and gloriously violent. A giant bladed dildo, a ludicrously long chainsaw, a hilarious pile of cocaine, the aforementioned spiked LSD, the aforementioned oracular chemist, a tiger, more than one offer of sex—Red encounters each as if it’s the rubble of a waking nightmare, fighting or consuming all of it. Every shot of Mandy reeks of shocking beauty, stylized at times to within an inch of its intelligibility, but endlessly pregnant with creativity and control, euphoria and pain, clarity and honesty and the ineffable sense that director Panos Cosmatos knows exactly how and what he wants to subconsciously imprint into the viewer. Still, Mandy is a revenge movie, and a revenge movie has to satiate the audience’s bloodlust. Cosmatos bathes Red (natch) in gore, every kill hard won and subcutaneously rewarding. There is no other film this year that so effectively feeds off of the audience’s anger, then sublimates it, releasing it without allowing it to go dangerously further. We need this kind of retribution now; we’re all furious with the indifferent unfairness of a world and a life and a society, of a government, that does not care about us. That does not value our lives. Mandy is our revenge movie. Watch it big. Watch it loud. Watch yourself exorcised on screen. —Dom Sinacola

15. Oddity

Year: 2024

Year: 2024

Director: Damian McCarthy

The success of Damian McCarthy’s Oddity is a testament to the Irish filmmaker’s ability to get the maximum possible mileage out of the smallest units of filmmaking verve. Compared to some of the other entries on this list, Oddity is understated, slowly paced, supremely patient. It depends almost entirely on the strength of its skin-crawlingly good opening sequence and a few key elements: The performance of Irish actress Carolyn Bracken, a unique and visually engaging shooting locale, and the creepiest goddamn mannequin ever put on the silver screen. Oddity is a story that happens in the wake of a brutal but mysterious tragedy, part of which we witness in its transfixing opening moments, which deliver a “what would you do in this scenario?” prompt for the ages. A woman is alone late at night in a creepy home being renovated, cut off from internet access or cellular reception, when a frightening looking man appears at her door. The agitated man insists that he saw an unknown person enter the woman’s home, that she is not safe because there’s someone in there with you. He begs her to open the door and allow him to come to her aid, seeming sincere despite his apparent derangement. So, which do you fear more: The potential threat you can see, or the one that may be hidden around the next corner? Rarely has any recent indie horror crackled with as much palpable tension as McCarthy immediately establishes here, and McCarthy milks it for all it’s worth.

Oddity then morphs, though, into a narrative happening in the wake of those opening moments, as the woman’s blind sister (Bracken), a clairvoyant with the power to read the energy and history of inanimate objects, investigates the circumstances of the crime. She knocks it out of the park, delivering one of the genre’s best 2024 performances as the incisive and prickly Darcy, a woman who suffers no fools even as she leverages a full bag of occult tricks in getting to the bottom of what happened to her sister. The most notable of which is of course the aforementioned wooden mannequin, an absolutely disturbing creation for which effects artist Paul McDonnell deserves special credit. In the mode of a filmmaker such as Demián Rugna, who made the motionless corpse of a young boy sitting at a dinner table nerve-shredding in 2017’s Terrified, McCarthy delights in playing here with the audience’s certainty that the malevolent mannequin will eventually–must eventually–be animated by some energizing force of revenge. Suffice to say, you’ll eventually get what you paid for, but Oddity’s true joys are in the moments before the madness; in Bracken’s cutting quips and steely resolve, and McCarthy’s mastery of eerie suspense. Thoroughly old fashioned and absolutely delightful, Oddity is simply expertly crafted and conceived horror filmmaking. —Jim Vorel

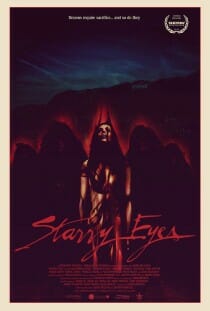

14. Starry Eyes

Year: 2014

Year: 2014

Director: Kevin Kölsch

Starry Eyes is a harrowing film experience, an ordeal, in the same way its protagonist’s journey is a major transformation. At the beginning, you think you have a pretty decent idea of the surface-level points Starry Eyes is trying to make; you get its “Hollywood against Hollywood” bitterness and cynicism about fame and the film industry’s pettiness. Then everything gets so much more destructive and subversive. Sarah (Alex Essoe) is a tragic figure, and this is a “horror tragedy,” if such a thing exists, made worse by the fact that she brings it all onto herself, fueled by deep-seated inadequacy and a crushing lack of self-identity. Her ambition turns her into a monster because she has nothing else: Her life is so devoid of meaning that doing the unthinkable has no downside. Hers, then, is a horrific self-destruction that leads into an abandonment of self and an orgy of truly grotesque violence, but there’s no joy or titillation in any of the ways it’s depicted. No one is going to describe Starry Eyes as light viewing, and no one is going to laugh at the deaths. You don’t show this thing at a party—you dwell on it in the depth of night while self-identifying with its horrors. —Jim Vorel

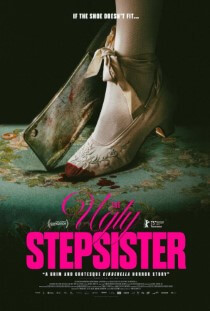

13. The Ugly Stepsister

Year: 2025

Year: 2025

Director: Emilie Blichfeldt

Feverishly funny, gruesomely gross and unrelenting in its satirical critique of both beauty standards and the designation of a cinematic “protagonist,” director Emilie Blichfeldt’s The Ugly Stepsister is a film that had jaws dropping at Sundance. A pitch black fairy tale reimagining of the story of Cinderella–conveniently premiering right before the 1950 Disney version of the tale celebrates its 75th anniversary–it reframes its story from the perspective of one of the titular “ugly” stepsisters, but then drives far beyond the idea of physical ugliness to get at the rotting sense of first sympathetic aspiration and later selfish entitlement and delusion that drives us toward our ultimate self destruction. And if there’s a more purely disgusting final five minutes in any other film in 2025, well … that would have to be a doozy, because The Ugly Stepsister delivers a denouement for the ages.

The Ugly Stepsister is an audacious debut for Blichfeldt as a writer-director, a beautifully captured and often quite funny piece of feminist social satire that builds to a conclusion of grand guignol that will likely leave some of its more squeamish audience members running for the aisles. Suffice to say, it’s the first iteration of Cinderella where one might want to be equipped with a barf bag for viewing, and if that’s not an apt sentiment for 2025, I can’t imagine what would be. —Jim Vorel

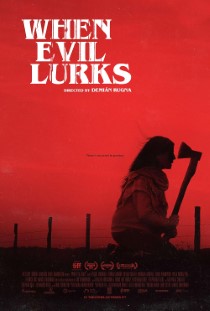

12. When Evil Lurks

Year: 2023

Year: 2023

Director: Demián Rugna

Director Demián Rugna’s debut horror feature Terrified has slowly but surely captured the attention of horror geeks around the world, but 2023’s When Evil Lurks is likely to complete his ascent to a star in the genre, even if he hasn’t yet produced an English-language feature. This is one of the most disturbingly creative and fraught possession horror films to arrive in decades, dropping the viewer absolutely cold into a setting where god is dead and evil is seemingly running roughshod over the Earth.

It’s deeply disconcerting to watch a horror film centered around demonic possession where the act of possession isn’t decried by the characters as some foolish impossibility, but is instead a well-understood facet of daily existence in this world. The arrival of a “rotten one” in a community is like the outbreak of an exotic and extremely deadly disease, requiring the presence of a specifically trained “cleaner” to dispose of the gestating demon in a way that doesn’t result in the entire area quickly becoming infected with evil. What happens when regular people have to deal with that kind of horror themselves? We quickly come to realize that there are a plethora of “rules” to surviving these encounters, but Rugna doesn’t handhold the audience and inform us of what they all are–every interaction instead becomes a paranoid question of wondering if the characters have become possessed, or vulnerable to attack. Never are we certain of what is true, and what is folklore. Pair this uncertainty with unflinching savagery and brutality, and you have one of the most gut-wrenching horror films to make its way to a small number of U.S. theaters in recent memory. —Jim Vorel

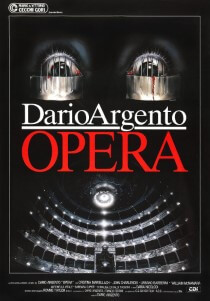

11. Opera

Year: 1987

Year: 1987

Director: Dario Argento

Giallo is not the kind of genre in which directors end up receiving a lot of critical aplomb—with the occasional exception of Dario Argento. He is to the bloody, Italian precursor to slasher films as, say, someone like Clive Barker is to more westernized horrors: an auteur willing to take chances, whose gaudy works are occasionally brilliant but just as often fall flat. Opera, though, is one of Argento’s most purely watchable films, following a young actress (Cristina Marsillach) who seems to have developed a rather homicidal admirer. Anyone who gets in the way of her career has a funny way of ending up dead, and her constant nightmares hint at a long-buried connection to the killer. Essentially the giallo equivalent of Phantom of the Opera, Opera’s canvas is splashed with Argento’s signature color palette of bright, lurid tones and over-the-top deaths. If you love a good whodunnit, and especially if you have an interest in cinematography, Opera is a primer in horror craftsmanship. —Jim Vorel

10. Blood and Black Lace

Year: 1964

Year: 1964

Director: Mario Bava

Blood and Black Lace plays like a missing link between Psycho or Peeping Tom and the classic “body count” slashers of the early 1980s, with a significantly more misanthropic attitude reveling in its on-screen violence. Perhaps the single most influential giallo film ever made, it codified some of the early tropes of a nascent film genre, innovated a few new ones of its own and did so with a sumptuous visual aesthetic that proved difficult for any of its imitators to match. In a career full of classics, it is perhaps Bava’s prettiest and most drum-tight film. The action takes place in a cavernous fashion house where high-end models are dressed, primped and prepared to don their haute couture and walk the runway, offering ample opportunity for the camera to both leer at a bevy of young women and examine the way they’re degraded by their industry, which treats them as little more than domesticated animals. When one of the company’s girls is violently murdered, it throws the entire organization into an uproar, with suspicion landing on almost every person employed in the building. What are we to make of the fact that none of the deaths can be traced to any individual? Bava ultimately uses a variety of simple (but effective) tricks to divert the audience’s suspicions until his big reveal. It’s the set-up for an old-fashioned murder mystery, but Blood and Black Lace also deviates from its forebears by being less concerned about the mystery and suspects on hand than it is with the killings themselves. This truly feels like a ground zero for the pulpy, grindhouse aesthetic that prioritizes cinematic death sequences, and the manner of the deaths, above all else. The unfortunate crew of models in the film bite the dust in all manner of ways, both inventive and notably grisly for the time, whether it’s burned to death by being pushed against a hot furnace, drowned in the bathtub or being stabbed through the face with a spiked glove. The film makes it clear: You are there to watch people die, and die in the most stylish way possible. –Jim Vorel

9. One Cut of the Dead

Year: 2017

Year: 2017

Director: Shiniichiro Ueda

Director Higurashi (Takayuki Hamatsu), beleaguered protagonist of Shinichiro Ueda’s box office indie smash One Cut of the Dead, has two modes: “On” and “in dire need of an ‘off’ button.” Even at his most sedate, Higurashi hums with the unharnessed energy of a pent-up greyhound, always at the ready for a race around the track but conditioned to patiently wait until the signal is given. Once it is, he’s a sight to behold, a man unleashed, screaming like a maniac christened as dictator, vaulting around sets with such vigor and dexterity to put the world’s parkour champions to shame. Hamatsu’s is the kind of performance that can only be contained by a specific kind of film. That film is One Cut of the Dead. Ueda first introduces Higurashi as a despotic indie filmmaker howling at his weeping star, Chinatsu (Yuzuki Akiyama), then 37 minutes later reveals the man to be a docile, much too obliging videographer who chiefly works on weddings and karaoke clips. It’s a glorious, bonkers 37 minutes, too, presented as a zombie movie shoot gone wrong. Higurashi and his cast—Chinatsu, former actress (and Higurashi’s wife) Nao (Harumi Shuhama), and pain in the ass leading man Ko (Kazuaki Nagaya)—and crew have set up shop at a decrepit, isolated warehouse that also stores a coterie of shambling undead. As they’re besieged by ghouls, Higurashi, yet to find a take that he actually likes, keeps on filming through the carnage. Of course it’s all a film-within-a-film. Once One Cut of the Dead shifts gears from a zombie movie to a backstage inside baseball comedy, the initially cold atmosphere Ueda establishes warms up. The amateur terror of Higurashi’s guerilla filmmaking gives way to winning charms as the audience gets to see who he really is, what this project means to him and just how damn hard it is to make a movie in a single take. It’s chaos, but it’s controlled chaos (even if only just), and in the chaos there’s absolute joy. One Cut of the Dead ends with smiles, pride, reconciliations and the accomplished sense of having achieved the impossible. If that’s not a ringing endorsement of collaborative art’s benefits, then what is? Maybe Ueda’s film is an odd messenger for delivering such high sentiment, but it’s the messenger we have, and we should embrace it. —Andy Crump

8. Exhuma

Year: 2024

Year: 2024

Director: Jang Jae-hyun

Writer/director Jang Jae-hyun’s Exhuma bobs and weaves in ways American exorcism stories couldn’t fathom. Shades of The Wailing’s transformative storytelling covers its haunted burial grounds, traditional exhumation practices and resentful spirits, all with filmmaking ambitions that think outside the (coffin) box. Exhuma presents as ordinary until it’s not, a splendid feature of slippery South Korean thrillers. Jang’s gravedigging ghost hunt takes multiple forms, each one more ferocious than the last, as nationalist histories manifest as a seething threat to modern generations. Exhuma follows a quartet of afterlife specialists: There’s renowned shaman Hwa-rim (Kim Go-eun), her full-body inked partner Bong-gil (Lee Do-hyun), “Geomancer” AKA feng shui master Kim Sang-deok (Choi Min-sik) and mortician Yeong-geun (Yoo Hae-jin). A wealthy Korean American family hires Hwa-rim and Bong-gil to eliminate a “Grave’s Call” curse afflicting their newborn son; Sang-deok and Yeong-geun are enlisted to help locate the problem ancestor’s grave. Together, near North Korea’s border, the party discovers a nameless tombstone. They’re in the right place, but Sang-deok can’t shake an alarming aura around the site. Some jobs aren’t worth the payday, as Sang-deok and his fellow undead bloodhounds are about to find out.

Jang’s approach welcomes international audiences into South Korean lore, where spirituality thrives without scoffs or sarcasm—it’s an immersive treat because there’s no disbelief or doubt to bog down the storytelling. Hwa-rim doesn’t waste time clashing against that one annoying pest who continually downplays supernatural experiences (the “they’re not real” plant). A propulsive energy trims fatty tropes off Exhuma’s lean cut of vengeful, hereditary malevolence. —Matt Donato

7. The Babadook

Year: 2014

Year: 2014

Director: Jennifer Kent

Classifying Jennifer Kent’s feature debut, The Babadook, is tricky. Ostensibly this is a horror film—freaky stuff happens on an escalating scale, so qualifying Kent’s tale of a single mother’s fractious relationship with her young son with genre tags seems like a perfectly logical move. But The Babadook is so layered, so complex and just so goddamned dramatic that categorizing it outright feels reductive to the point of insult. There’s a grand divide between what Kent has done here and what most of us consider horror. You’ll spend your first week after the experience sleeping with the lights on. You will also come away enriched and provoked. Australian actress-turned-filmmaker Kent has made a movie about childhood, about adulthood and about the nagging fears that hound us from one period to the next. There’s a monster in the closet—and under the bed, and in the armoire, and in the basement—but the film’s human concerns are emotional in nature. They’re not aided by the ephemeral evil lurking in the dark places of its characters’ hearts, of course; going through personal trauma is enough of a chore when you’re not being stalked by the bogeyman. —Andy Crump

6. The Bride of Frankenstein

Year: 1935

Year: 1935

Director: James Whale

Egregiously omitted from most “best sequel” discussions, this darkly inventive would-be love story may well be the finest of the golden-age Universal monster movies. With its extravagant gothic aesthetic and timeless Hollywood mores (“We belong dead!”), the film is the face of an era and a fearsome inspiration to many that followed, featuring Boris Karloff’s best overall performance as the tortured monster. —Sean Edgar

5. A Dark Song

Year: 2016

Year: 2016

Director: Liam Gavin

In Liam Gavin’s black magic genre oddity, Sophia (Catherine Walker), a grief-stricken mother, and the schlubby, no-nonsense occultist (Steve Oram) she hires devote themselves to a long, meticulous, painstaking ritual in order to (they hope) communicate with her dead son. Gavin lays out the ritual specifically and physically—over the course of months of isolation, Sophia undergoes tests of endurance and humiliation, never quite sure if she’s participating in an elaborate hoax or if she can take her spiritual guide seriously when he promises her he’s succeeded in the past. Paced to near perfection, A Dark Song is ostensibly a horror film but operates as a dread-laden procedural, mounting tension while translating the process of bereavement as patient, excruciating manual labor. In the end, something definitely happens, but its implications are so steeped in the blurry lines between Christianity and the occult that I still wonder what kind of alternate realms of existence Gavin is getting at. But A Dark Song thrives in that uncertainty, feeding off of monotony. Sophia may hear phantasmagorical noise coming from beneath the floorboards, but then substantial spans of time pass without anything else happening, and we begin to question, as she does, whether it was something she did wrong (maybe, when tasked with not moving from inside a small chalk circle for days at a time, she screwed up that portion of the ritual by allowing her urine to dribble outside of the boundary) or whether her grief has blinded her to an expensive con. Regardless, that “not knowing” is the scary stuff of everyday life, and by portraying Sophia’s profound emotional journey as a humdrum trial of physical mettle, Gavin reveals just how much pointless, even terrifying work it can be anymore to not only live the most ordinary of days, but to make it to the next. —Dom Sinacola

4. Mad God

Year: 2022

Year: 2022

Director: Phil Tippett

Though it begins by quoting the 26th chapter of Leviticus—“I will lay your cities in ruin and make your sanctuaries desolate and I will not savor your pleasing odors”—Mad God plays out like the Book of Revelation. Punishment and apocalypse are writ large and brown in feces and industrial run-off. Medical malpractice means more than negligence, it means quacks and ghouls elbow-deep in your guts. All is grist, everything is decay, human bodies little more than rag dolls made of shit. A so-called “She-it,” a screeching, walking tumor of hair and bared teeth, defends her beaked young against the mania of Mad God’s wasteland, wielding a cleaver. (All while I crammed so-called “Cheez-Its” down my gullet, watching and ceaselessly consuming.) Your pleasing odors escape un-savored into the ether. And just when you think you’ve reached the bottom of Hell, convinced there are no more realms of the beyond left to unveil, you see there is always more bottom, always more beyond. You see whole universes of innocent creatures suffering behind heavy vault-like doors, within the memories of one disposable martyr after another, in the spaces yet to be born. In a series of ever-obliterating visions, Mad God reduces the human experience to cosmic chum. It’s deeply upsetting, and often just as stirring. It would be a pretty clearly nihilistic piece of work, too, were it not such a careful, frequently astounding achievement. A stop-motion film 30 years in the making—beginning with an idea sparked during a lull in shooting Robocop 2—Mad God is mostly the work of one man, legendary animator Phil Tippett, every elaborately nauseating set hand-fashioned over the course of decades. In Mad God, life seems meaningless. Stories don’t end when protagonists die because there are only antagonists running reality. And yet, as punishing as the film can get, it’s also clearly, fully realized, as pure a translation of a remarkable man’s bodily prowess—action, reaction, sinew and muscle and bone in tandem, the heartrending inertia of all things moving toward obliteration and the patience to let that happen—as we’re privileged enough to get from someone who’s already given us so much of himself. For all the grossness, all the bodily fluids and misery and Dan Wool’s charmingly contratonal music, for all the cynicism about the nature of the human race, Mad God is ultimately hopeful. It’s an absolution, for Tippett and maybe for us too. Nothing that’s taken 30 years, and so much health and sanity, could be anything but.—Dom Sinacola

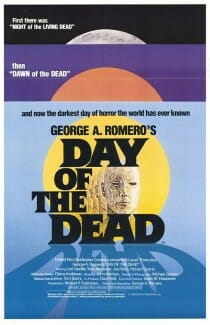

3. Day of the Dead

Year: 1985

Year: 1985

Director: George A. Romero

Although Dawn will probably always have more esteem, and is significantly more culturally important, Day of the Dead is my personal favorite of George Romero’s zombie films, and I don’t think it ever quite gets the respect it deserves. It comes along at a sort of sweet spot–bigger budget, more ambitious ideas and Tom Savini at the zenith of his powers as a practical effects artist. The human characters this time are scientists and military living in an underground bunker, which for the first time in the series gives us a wider view of what’s been going on since the dead rose. This film reintroduces the science back into zombie flicks, finally making one of the main characters a researcher (Matthew “Frankenstein” Logan) who has had some time to study the zombies in the relative safety of a lab. As such, the movie redefines the attributes of the classic Romero ghoul–they’re dumb, but not entirely unintelligent, and some of them can even be trained to use tools and possibly remember certain aspects of their previous lives. That of course brings us to “Bub,” maybe the single most iconic zombie in Romero’s oeuvre, who displays a unique level of personality and even humor. Day of the Dead ultimately takes a monster that audiences thought they knew pretty well at this point and suggests that perhaps they were only just scratching the surface of zombies’ potential. —Jim Vorel

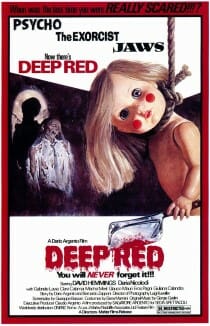

2. Deep Red

Year: 1975

Year: 1975

Director: Dario Argento

Dario Argento movies would be exceedingly easy to pick out of a police lineup, because when you add all of his little quirks together they form an instantly iconic style—essentially the literal definition of auteur theory. Deep Red is one of those films that simply couldn’t have been made by anyone else—Mario Bava could have tried, but it wouldn’t have the instantly iconic soundtrack by Argento collaborators Goblin, nor the drifting, eccentric camerawork that constantly makes you question whether you’re seeing the killer’s POV or not. The story is a classic giallo whodunit: Following the brutal murder of a German psychic, a music teacher who lives in her building starts putting the pieces together to solve the mystery, uncovering a tragic family history. Along the way, anyone who gets close to the answer gets a meat cleaver to the head from a mysterious assailant in black leather gloves. Except for the ones who die in much worse, more gruesome ways. Argento has a real eye for what is physically disconcerting to watch—he somehow makes scenes that are “standard” for the horror genre much more grisly and uncomfortable than one would think, simply reading a description. In Argento’s hands, a slashing knife becomes a paintbrush. —Jim Vorel

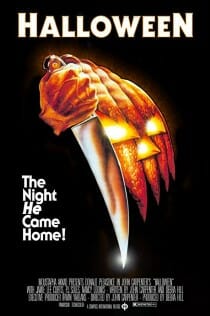

1. Halloween

Year: 1978

Year: 1978

Director: John Carpenter