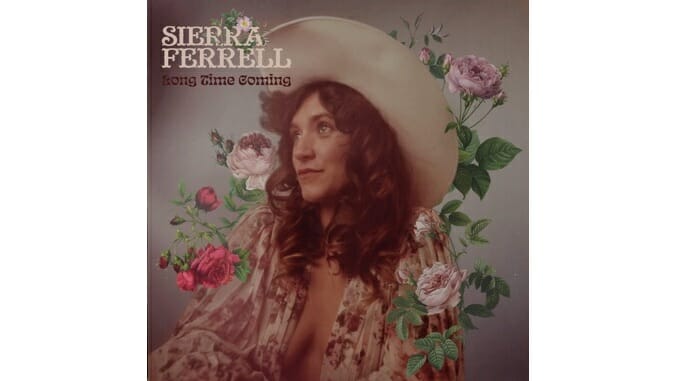

It’s a Long Time Coming, But Sierra Ferrell Has Figured Herself Out

You may listen through Sierra Ferrell’s new album, Long Time Coming, and come out the other side with only the haziest idea who she is, and that’s okay. The state of not knowing is all the more reason to absorb the album’s countless influences, the varying wavelengths on which each track exists, and the way the record’s dexterity tells us all we really need to know about Ferrell as a musician: She’s the sum of her journeys around the U.S., from New Orleans to Seattle, not easily defined and impossible to pigeonhole. Also, she’s very talented. That matters, too.

There’s Nashville in Long Time Coming, naturally, that being the place she now calls home. But Ferrell grew up in West Virginia and busked all over the place before the road took her to the Music City. Ferrell’s style meanders. One moment she’s singing a waltz, whether on “West Virginia Waltz” or “Whispering Waltz.” The next, she’s belting out a classic folk-country story about an unrequited and oblivious love in “Bells of Every Chapel.” Frankly, the album opener, “The Sea,” a ditty soaked in brine and with a plea to Poseidon on the chorus, is a giant, screaming hint at how far and wide Ferrell will take her audience from beginning to end.

Long Time Coming weaves a melancholic kind of magic with that mythological invocation. It’s a bold choice to kick off an album that has nothing to do with Greek gods by begging one of them for help: “So Poseidon give me life / Let me breathe like a Pisces with blue eyes.” But it’s also normal for humans in love to seek divine intervention, and Ferrell is nothing if not human. She’s quirky, too, of course, and an utterly compelling frontwoman as a result. “The Sea,” for instance, doesn’t read as the product of Nashville’s music scene, but rather like a bit of cabaret that’s only broadly identifiable as “Southern” thanks to Ferrell’s twang and, tangentially, a deep-rooted sadness sourced from her inability to keep her lover’s eye from wandering.

That contrast between romantic misery and the ocean comes up more than a few times on Long Time Coming: It’s there on “Why’d Ya Do It,” too. “My love for you’s a deep blue ocean, baby / I just wanna swim inside,” Ferrell hums on the very first verse, determining later on that she ought to find someone “who won’t tear my world apart.” This is a fundamental subject in country, roots music, folk and Americana, the old stereotype people with no fondness and lots of contempt for all these genres like to foist on them. Singers either mope about losing their car, their dog or their spouse in country music. Long Time Coming is the product of Ferrell’s personal “stuff,” accrued over years of performing in venues and on streets; it’s fair to assume she picked up her share of heartbreaks along her way, too.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-