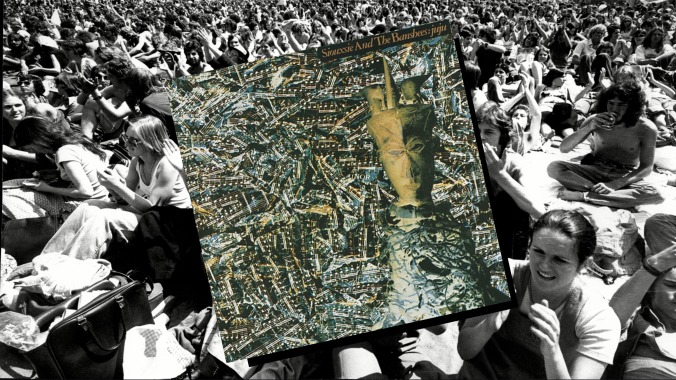

Time Capsule: Siouxsie and the Banshees, Juju

Subscriber Exclusive

Every Saturday, Paste will be revisiting albums that came out before the magazine was founded in July 2002 and assessing its current cultural relevance. This week, we’re looking at Siouxsie and the Banshees’ Juju, a horror-filled, 1981 masterwork draped in a suspense that thrives on fantastical trips through the depths of post-punk’s darkest pits.

By 1981, Siouxsie and the Banshees had already made their mark in the post-punk mecca with their darker twist on the emerging rock sound. On their 1978 debut album The Scream, Siouxsie Sioux’s siren screech evoked a menacing quality all on its own. Paired with the jarring rhythms of John McKay and the unorthodox drum recording methods of Kenny Morris, you can see where the effortlessly unique quality of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ sound originated from. The Scream is the most traditionally punk-sounding record the group ever put out, and until Juju arrived three years later, it was their most affecting and intense release.

Throughout the many iterations of Siouxsie and the Banshees, particularly on the front end of their existence, the lead guitarist position was a rotating cast of everyone from a pre-Sex Pistols Sid Vicious to a post-Pornography Robert Smith, though the two most influential on the group were guitarists John McKay and John McGeoch. Following their debut, McKay and Morris stuck around for the band’s criminally unappreciated sophomore release, Join Hands, before departing and being replaced by ex-Slits/Big In Japan drummer Budgie and former Magazine guitarist John McGeoch. On Kaleidoscope, the Banshees shifted their sound with the incorporation of synthesizers and drum machines that would later get (mostly) abandoned for Juju.

Riding Kaleidoscope’s wave of critical success, which was their first collaboration with Grammy-nominated producer Nigel Gray—who produced for the Police on Outlandos d’Amour , Reggatta de Blanc and Zenyatta Mondatta—Siouxsie and the Banshees created their own mystical charm with Juju. It was a horror-filled masterwork draped in a suspense that thrives on fantastical trips through the depths of post-punk’s darkest pits. The record’s narrative unfolds with an urgency that demands attention, especially as it submerges you into a world of shadowy sexuality, eerie entities and thrilling tales.

Siouxsie and the Banshees have an uncanny ability to evoke sexiness via the unsettling, and Juju is their magnum opus of disquieting seduction. The record is a particularly creaky house of horrors, populated by a wailing woman dressed in all black wandering its halls with ominous screeches eking out from the guitar soundtrack, bathing the scene in delicious dread. The magical effect of Siouxsie and the Banshees’ fourth album is heavily due to their shift back to guitar-centric music, with John McGeoch’s unconventional six-string work front-and-center.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-