- Welcome to Daytrotter

- Does Me No Good

- When Push Comes To Love

- That Train That Carried Away My Girl

- Dry

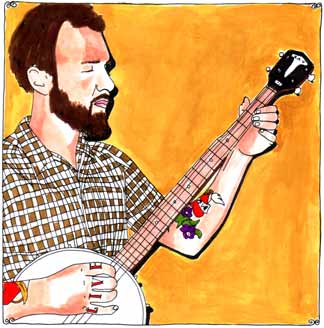

William Elliott Whitmore doesn’t believe in a heaven or a hell. He believes in his home state of Iowa, a place kind of halfway between both. He sings ebulliently about cold, black Iowa dirt being tossed onto his coffin lid after he’s been levered down into his grave and how it runs through his veins, getting muddy when the skies open up to drop off some precipitation (Whitmore might call it a puker depending on the strength and duration), usually the prayed for kind. He wants to roll around in it and rub it into his teeth. He loves when it’s under his feet. During the summer months, he orders his booking agent to keep his schedule light, allowing him the opportunity to savor as many of the summertime days working on his farmer’s tan, going fishing barefooted and casting a line into a limpid family pond for whatever might nibble, tug and put up a fight. The great Mark Twain – born in Hannibal, Mo., only a few hours paddle down the Mississippi River from Whitmore’s home in aloof little Montrose, Iowa – chronicler of all-American boyhood, could have used him as a character study, then blushed a little as Will grew unpredictably into the tattooed man he is today.

Twain would have proudly worked it into his humble prose as Whitmore would never have let him down. He doesn’t let anyone who’s followed him through his career down, feverishly picking his banjo – a junky, rusty thing that remarkably sounds sweeter than molasses – stamping his dress-shoed foot for instant heartbeat drums and writing words that make the malaise and the profundity of living all these consecutive days sound like they’re not to be feared, but to be seen as the reasons why goodness exists. It doesn’t just happen. Whitmore assures us that there’s no take without the give. If a loved one is lost, a flower blooms beside a headstone in Whitmore’s songs. Deaths, while unfortunate and sad, are grains of salt in the songs on his three Southern Records releases. They exist to steel you, to make room for perspective – to add that meaning to life. Oh, that’s nothing new to suggest – that death staggers you and reinforces the need to make everything count – but Whitmore’s way of making his point, with a voice as heavy as an anchor and enriched with the husky rawhide of a man four times his age, resounds like a brick dropped down a wishing well. It’s darkly lit and it gives his songs, all of which have an unmistakable amble, a timelessness that carries the authority of ghosts.

Whitmore’s view of life stems directly from his upbringing. Growing up on a 160-acre horse farm in Lee County, he was intimately attuned to the cycles that exist in nature at an early age. It wasn’t the end of the world when an animal died. It was part of the process, not an abstraction. When they planted crops that then got massacred by a drought, sending all those counting on a harvest into the winter scared of how they would pay the bills and put food on the table for their families, it was sad. And when people died, it was sadder, but the sweet follows the sour. He learned that best after he lost his father to cancer over 10 years ago as a sophomore in high school and then lost his mother three years later in a motorcycle accident. Those two events severely bruised and dented a young man who hadn’t the faintest idea of what he wanted to do with his life at the time. He began writing songs because he couldn’t paint about the things he found loitering up in his head. He found his outlet for all of the feelings that wouldn’t stop stinging inside. They manifested themselves into first Hymns for the Hopeless, then 2005’s Ashes To Dust and this year’s stunner Song of the Blackbird, a work that is affirming. You can feel something light up beneath your skin that is absolutely beyond your control. It might just be a small reflection of the candlelight Whitmore says he reads by in his cabin or the burnt orange of the wood that provides his heat, crackling in his stove. Or, it might just be that you suddenly found yourself taken with a lyric like, “The song of the blackbird is mighty loud/Through the evening mist/The moon is up and it looks so proud/To be looking down on a night/On a night like this.” You feel sick with love. You’ll be hung over with those words in the morning when you wake up. It won’t be because of any corn whiskey or moonshine, no sir.

Whitmore could be a church, a religion in a completely secular way. If a religion could be trusted to tell it like it is without the guilt and the shame and the bullshit, you’d want Whitmore to be an official choice – on the ballot. Sunday mornings would be something, wouldn’t they? It would be the best hour spent all week.

The Daytrotter interview:

*You’ve never paid bills before?*

William Elliott Whitmore: I’ve been an adult for a long time, but I’ve lived life in such a way that I never had to pay bills. It’s really new to me.

*Do you think you live up to a lot of the images people who listen to your music might have of you? Having a cell phone isn’t one of them.*

WEW: I suppose so. I do live up to some of those, but I do drive a mini van. I definitely feel like the way I grew up…I had good things from both worlds. I had the rural and I had the cities. My old man was just a real simple guy in his possessions. My place is so simple. It’s just like a tin shack. I’ve got a wood stove for heat. I love it. I wish everyone could come and see my place.

*How is your cabin coming along?*

WEW: I would say it’s 80-percent of the way done. It’s just an old corn crib. I don’t have a bathroom yet and I don’t have electricity. That’s kind of the next major thing. I have an extension cord running from the barn to my place now so that I can have my little boombox. But I’ve got to get electricity so I can have my fuckin’ stereo and I can play my records. You’ve got to have that stereo. Other than that, it’s cozy as shit. It just feels so good and that wood heat…I’ll just keep working on it. I’ll probably build some hallways that go nowhere like the Winchester house. I read about how the widow of the Winchester gun fortune would add on to her house. Ghosts would tell her what to build and she had all this money so she kept adding on. She had all these hallways that didn’t go anywhere. I thought that was great.

*How many acres is the farm?*

WEW: It’s 160 acres. It’s pretty cool because the neighbors on three sides are also family. We had a shrewd, shrewd great grandpa who bought all this land. We’ve got our area pretty much all to ourselves. It’s like a big family compound.

*And it used to be a horse farm, right? Any animals there now?*

WEW: I’ve got an old quarter horse and I’ve got an old mule named No. 13. I just kind of keep them around as pets. My uncle calls them hayburners.

*Is the name No. 13 a reference to Mad Jack’s burrow named No. 7 in “Grizzly Adams?”*

WEW: Yep, yep, that’s exactly where it’s from. I think you’re the first person to have ever gotten that. I used to love that show. It was actually a real inspiration for me. I’d watch it and I would be like, “Goddamn, he doesn’t have to answer to anyone.” It’s taken me a long time to build up, but I’d always had the vision, as a kid, that this would be the perfect life. Every other job I ever had was just a show job. You know, you get these show jobs and you’re like, “I need to get this paycheck so I can leave for tour for a week” or you need that paycheck for art supplies to make your art. They helped me to work toward this. I worked at Hardees for a year when I first started doing the music thing. We’d ride our skateboards in the parking lot until it was time for our shift. It wasn’t all bad. We made the best of the situation. It’s like anything, you just try to do it the best that you can. I always had dreams of doing stuff with music, but at that time, it was like trying to wrap your arms around the moon. You can do that, but in the meantime, you have to keep the lights on.

*When did you realize that it wasn’t like wrapping your arms around the moon, that you could actually do it?*

WEW: We’d drive up to Iowa City and see shows at Gabe’s (now The Picador). You could sneak into shows when you were underage and sometimes they’d have all ages shows. There also used to be a church there that would have punk and hardcore shows in its basement. I had never seen things like that before. There were all these kids getting all bloody and crazy in this basement and it was awesome. You could actually do this in a basement. It was the first time that I thought I could do something. I could get a show in a basement and I could get one in the next town over and the next town. Pretty soon you had a tour. I would go up to Dubuque (Iowa). It was just meeting the right folks. I met the Ten Grand guys and those kids had computers and shit. They had all the right connections and they knew the right cats. I tagged along with them. It was always like, “Me too, right?”

*There’s so much of it all over your songs. What’s your take on life and death?*

WEW: They’re equally powerful. You can’t have one without the other. I don’t believe in a heaven or a hell. I just think there’s a certain amount of energy in the universe. I feel fortunate in the lessons I’ve learned. I learned a lot about life and death growing up on the farm, where your horses die and things die. It’s not really a bad thing, it just is. I could talk for hours about this shit. Both of my folks passed away when I was younger. My old man died when I was 16. He had cancer. And my mom died when I was 19. She was a motorcycle rider and someone ran a stop sign. My old man’s death was kind of slow and protracted. My mom’s was so sudden. That kind of made me go crazy. It just kind of made me go off the deep-end. I just tried to really pull myself together. That’s when I really started playing music. If my folks hadn’t died, I’d probably be baling hay right now. Not that that would be a bad thing, but my life wouldn’t be the same. I think I appreciated that. I just wanted to bury myself. I just wanted to fuckin’ die, but I couldn’t. I realized that I could become the man I needed to be right now. Everyone’s sad, but I’ve got to man up and saddle up. I was definitely forced to grow up.

*What’s your favorite tattoo?*

WEW: My favorites are the ones of the Eastern goldfinch – the Iowa state bird – and the wild rose – the Iowa state flower. I got my first tattoo when I was 18 because you can’t really get a tattoo before than, but I wanted to so bad. I thought, “You can put artwork onto your body? How cool is that?” The first thing I got was just something decorative. When you’re young, you think you know a lot of shit, but you don’t know shit. I still don’t know shit. Your tattoos kind of reflect that.

*Why do you love Iowa so much?*

WEW: The area that I live in is very nice. Some parts of Iowa are just flat and full of nothing. When you’re less wise, you want to get out of here. I wanted to split. I just wanted to see the world. I just rambled all around and everywhere I went, I found that I missed home super bad because it was my home. There are great nooks and crannies all over the world, but there’s only one home. If you’re from Eugene, Oregon, then Eugene, Oregon’s the shit. I love home because there’s no pavement and you’ve got that Mississippi River right there.