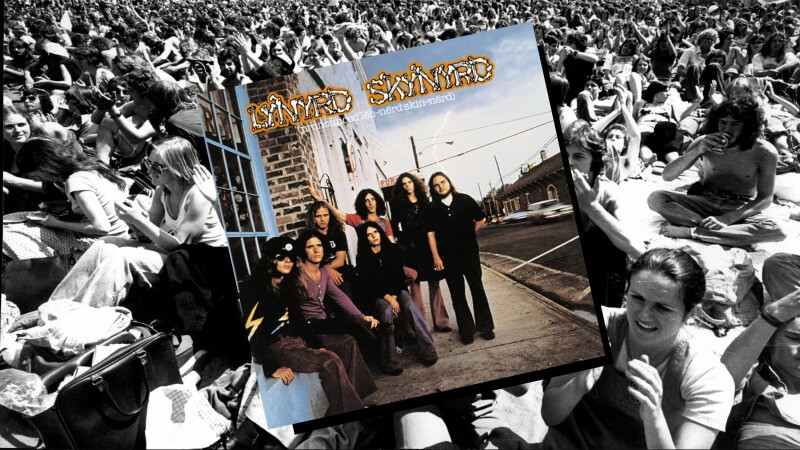

Time Capsule: Lynyrd Skynyrd, Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd

The Jacksonville sextet’s debut album was a Southern rock joint potent with fire, whiskey, and big-screen riffs. The songs they cooked up were ragged and muscular, displaying a convincing body of country-fried gravitas.

Though the band formed in Jacksonville, Florida in the mid-‘60s, most music students (and casual listeners, too) know well the tragedy that hit Lynyrd Skynyrd a decade later: a plane crash killed vocalist Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist Steve Gaines and his older sister, backup singer Cassie Gaines, on October 20, 1977 in Mississippi, badly injuring the rest of the group, Gary Rossington, Allen Collins, Larry Junstrom, and Bob Burns, in the process. Skynyrd’s career immediately went on pause, remaining dormant until a reunion 10 years later featured Ronnie’s brother, Johnny Van Zant, singing lead. The core lineup made five albums together—some great (Street Survivors), some lopsided (Gimme Back My Bullets), and some right down the middle (Second Helping; Nuthin’ Fancy)—but none of them usurp the endurance of Skynyrd’s debut, Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd: a Southern rock joint potent with fire, whiskey, and gigantic riffs.

In my head canon, the Lynyrd Skynyrd that reunited in the ‘80s with Johnny in the saddle is a different band entirely. Ronnie was the soul of the first iteration, his legacy imagined and immortalized in the 43 minutes it takes to sit with every ounce of Pronounced. His twangy drawl held powerful dimensions, fluttering between an E5-reaching stadium rasp and gentle, bedside coos. His range wasn’t technically impressive, but his conviction was next-to-none. I call it “everyman singing,” in that his performances felt no more spectacular than the urchins you might hear cutting it up at your local dive. Perhaps I am drawn so easily to Skynyrd’s catalogue because those songs could have been built by any group of dudes making noise in a shed. You probably know a guy or two as talented as Van Zant or Rossington and Collins were. Those Florida boys weren’t tone-chasing, they were shredding—and Van Zant’s voice was the badass, unpretentious glue.

In the years leading up to Pronounced ‘Lĕh-‘nérd ‘Skin-‘nérd, the rock genre was catapulted first by Deep South blues players like Bo Diddley and rock first-wavers like Jerry Lee Lewis and Fats Domino. The British Invasion, Greenwich Village scene, and impending psych-rock introduction plucked rock and roll out of the South and relocated it across the US and UK. It was Lonnie Mack and Dale Hawkins’ surging popularity in the mid-‘60s that opened the door for the Allman Brothers Band to form in Jacksonville in 1969. Then came the panhandler Leon Russell, Texan Janis Joplin, and swamp rock picker Tony Joe White. And then came Lynyrd Skynyrd, led by a 22-year-old crooner in a hi-roller hat.

Around that time, Al Kooper—the multi-instrumentalist who played on Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” and the Stones’ “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” and later formed Blood, Sweat & Tears—discovered Skynyrd in Atlanta. He wanted to manage them, and he wanted to produce their debut album. So, he took on the pseudonym “Roosevelt Gook,” plucked the sextet out of their “Hell House” rehearsal space in Jacksonville, and brought them to Studio One in Doraville in 1973. For five weeks, they laid down takes of songs they’d already perfected on the road. Kooper denied improvisation yet was in awe of the taut, worn-in synergy Skynyrd had built through gigging around Jacksonville. But, in one of Kooper’s few missteps as Skynyrd’s veteran steward, he was against “Simple Man”’s inclusion on the album. The story goes that he and the band couldn’t come to an agreement about the song’s fate, so Van Zant made Kooper sit in his car until the recording was finished. And then, after taking the now iconic cover photo full of ghosts on Main Street in Jonesboro, Rossington promptly puked on the nearby sidewalk.

Before the plane crash in 1977, all five of Skynyrd’s records were eight songs long. I’m no rocket scientist, nor am I an expert on sequencing, but I’d reckon that eight songs is the perfect length for a rock and roll album. Limiting the tracklist helped trim the fat, which is why Pronounced is a no-skips effort. Even the “weakest” installments, like “Mississippi Kid” and “Things Goin’ On,” are big blues idioms speaking in the cursive of carnal guitar strokes. Each side of the record oscillates between cocksure chords and chest-bursting drum storms. Opener “I Ain’t the One” snarls and screams, with Allen Collins’ lead lines doing all the talking. Brief keyboard solos unfurl in one ear, while seam-splitting riffs explode in the other—all while the swaggy undercurrent of Gary Rossington’s rhythm guitar twists and repeats. “Poison Whiskey,” Van Zant and Ed King’s alcoholism cautionary tale, is ornery and robust; Van Zant sings about a street-fighting Cajun man who drank himself dead after “20 years of rotgut” and warns the “people” that there’s no future in a bottle of Johnny Walker’s Red.