The Longest Week

The Longest Week is the feature debut of writer-director Peter Glanz, and Los Angeles-based production company, YRF Entertainment. It was adapted from Glanz’s black-and-white short, A Relationship in Four Days, which premiered to modest acclaim at Sundance in 2008. As is often the case when a heralded short is expanded to feature-length, much more is lost than is gained in Glanz’s freshman effort.

In the film, Conrad Valmont (Jason Bateman) struts around as a product of his privileged New York environment. From his therapist-since-childhood’s chair, he basks in high-minded lethargy as he references George Bernard Shaw. Having spent his formative years in upper-crust private schools, Valmont knows how to say things like “I feel like Napoleon after Waterloo, dying in exile on the coast of St. Helena.” And he’s a middle-aged adult in the 21st century, so he’s been trained to label all forms of internal repression as “Freudian.” He’s in the gathering stage of his sophomore novel, a stage now rounding 10 years. (That his freshman effort was never finished is all the more reason to not rush, lest the second fall victim to the pitfalls of the first.)

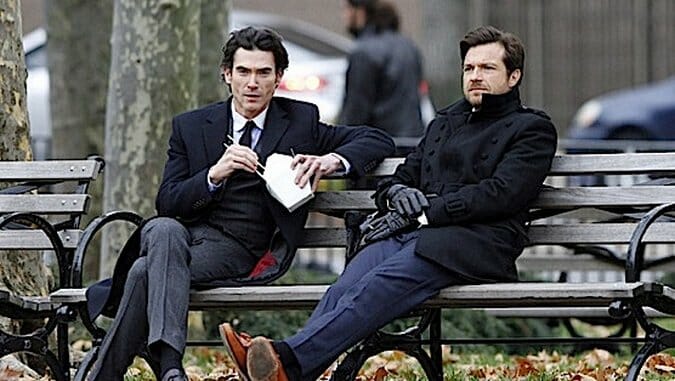

Following the unanticipated divorce of his parents, Conrad has his bank accounts frozen and is evicted from his family’s Valmont Hotel, leading him to seek shelter with longtime friend and “antisocial socialist, closet conversationalist,” Dylan Tate (Billy Crudup). Soon, Conrad strikes up an affair with Dylan’s model/bookworm/cat-eyed sweetheart, Beatrice Fairbanks (Olivia Wilde), in one of the more effeminate displays of girlfriend swiping. She likes the way he looks at her, and he likes the way she bites her lip before she starts playing the piano.

In its best moments, The Longest Week is a comedy, but those moments are obscured by waves of stuffy historical references (“You have the moral code of a Bolshevik!”) and truisms. The script is so shameless that out the gate there’s a temptation to consider The Longest Week satire, but then come obvious lines like “Conrad often became attached to the idea of something, and not the actual thing itself,” and “There was one thing that rendered them incompatible … she was a hopeless romantic, and he was romantically hopeless!”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-