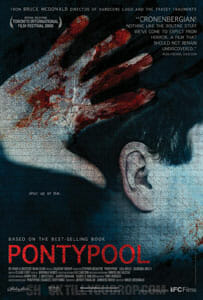

Pontypool

Release Date: May 29

Director: Bruce McDonald

Writer: Tony Burgess

Cinematographer: Miroslaw Baszak

Starring: Stephen McHattie, Lisa Houle, Georgina Reilly

Studio/Run Time: IFC Films, 95 mins.

Talk-radio zombies from Canada

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-