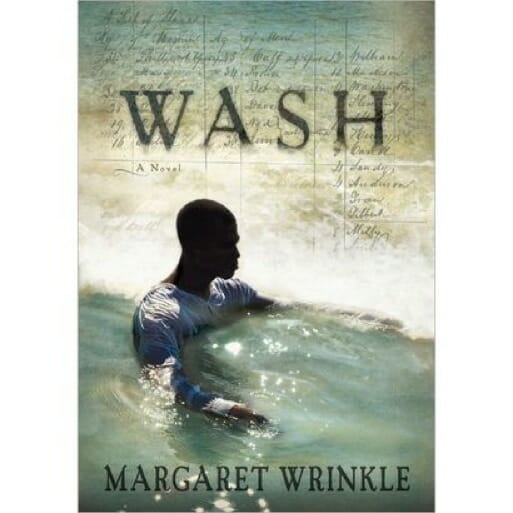

Wash by Margaret Wrinkle

A story of gist, a gist of story

Margaret Wrinkle’s debut novel comes better packaged than built, but package and build come, curiously, with slick black-and-white photos of rustic scenes—a barn door with a chain latch, a clapboard house, etc.—opposite the title pages of its seven parts. Is this in case we’re unfamiliar with rural Southern living? Even this reminder reminds that some of us need reminding that we live far removed from the War of 1812 and its after-years. A 19th-century mood can’t be an easy thing to set, even with no distractions.

This debut novel by Alabama-based Wrinkle begins with an unforgettable tableau—a prologue that tells of the protagonist’s slave face bearing the brand of the runaway R on one side and the scar from a hammer blow on the other. We absorb the compelling gist of a story—that this slave, Wash (short for Washington), lives as a breeding stud, populating a nation of Washes (each with “wide brows like wings”) that slave owners sell off for good money.

The book also begins with a hint that something somewhere isn’t plumb in this sentimental telling.

The trouble starts early. Apparently, the story’s narrators have congregated in a nondescript room, dark as forgotten time, where they provide our story piecemeal à la As I Lay Dying—but more self-consciously woven, transitioning one voice to the next, because, well, they’re in the same room, perhaps an auditorium, listening politely to each other and taking turns at the mic. The narrators adopt each other’s metaphors, share similar concerns and histories, use the very same narrative techniques.

Like Faulkner’s novel, Wash predominantly rotates between first-person accounts integral to three main storylines:

• Wash.

• Wash’s secret love, Pallas, also a slave and healer in their Tennessee community.

• Wash’s master, Richardson, a veteran and POW from both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

Then our author adds a new wrinkle: a third-person omniscient narrator.

This voice zooms in so close to characters, those previously mentioned as well as others, that for all intents and purposes it proves nothing more than a series of veiled first-persons—a catch-all that trades the consistency of the carefully delineated point-of-view sections for convenience.

The trouble with this third-person point-of-view, written in conversational present tense? It reads more as hearsay than history, particularly when the narrator interjects personalized commentary.

When Rufus, a slave and blacksmith who mentors young Wash, tells his hot-tempered female companion that “she best be careful where she lets her mind go because it remembers and holds the tracks of every step,” the narrator follows with what Wrinkle must believe is a necessary aside: “And he’s right.” But necessary … why? Is it to allay concerns that the reader may doubt the profundity of Rufus’ belief … or, a more damning possibility, the integrity of the omniscient narrator’s paraphrase?

This reductionist approach to storytelling appears to imply, despite the Freudian slip of the aside, that summary and paraphrase reign supreme in every way possible, at the expense of well-set, well-described scenes and … well … storytelling.

Is knowing superior to wondering? Does truism beat nuance? Whatever else, Wrinkle’s approach diminishes suspense, makes every voice generic and takes away verisimilitude.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-