It’s difficult to know where to begin here, because I’m on fire with this show in a way that hasn’t happened since—when? The Wire? But The Wire is organized and clinical and entirely different, lighting unrelated, landlocked pleasure zones of the superego, so the comparison doesn’t make sense. Different passions, different planet altogether. This, this True Detective, is an offering of a separate magnitude, something bright and intelligent yet ultimately murky, ultimately of the id.

I don’t think we’ve seen its equal, maybe ever. You can make a mistake and hold yourself back and reach out grasping for similarities in shows past. There are others that have used dark ominous backdrops and an unsolved murder to explore the damaged psyches of the living … well, let’s think now, there’s Broadchurch and The Killing and Luther and Top of the Lake and Wallander and The Bridge and Low Winter Sun and Hannibal and Line of Duty and The Shadow Line and God knows what else, but these all ring hollow by comparison. There’s contrivance in those others, where here we have a world that resembles ours but is tilted totally off the usual axis. You feel like if you could find whatever lens Nic Pizzolatto (creator, writer) and Cary Joji Fukunaga (director) use to refract the narrative, you might be laid low in some blackened fugue, but you’d also have the secret to life. Whether you wanted it or not.

I once covered a basketball game where there was bad blood everywhere and near-fights and coaches yelling and all kinds of drama. We gathered in the media room after, the winning coach came in, and some clueless reporter possessed by curiosity’s opposite raised his hand and blinked his uncurious eyes and asked about some forgettable strategical gambit. We stared at him in disbelief, then in anger, daggers coming from every corner—why would you waste a damn question on that when real things were happening? So I won’t be like him a second longer; no more burying the lede, which is:

Matthew F***ing McConaughey. He’s the beginning and the end of this show. No matter what else happens, he’s the vortex of energy to which everything returns. Magnetic, dynamic, elemental. After watching the second episode, I ran off to a video store (yeah, really!) and rented Mud and Magic Mike because, to intellectualize the naked fact that I couldn’t get enough, I felt like I should start to understand this renaissance in all its dimensions. (Aside from this parenthetical, I refuse to call it the “McConaissance,” because it reflects a desire to categorize things and distance ourselves with cute names, and it diminishes the raw stunning essence of whatever is happening with this man, which should be experienced up close in fever-dream proximity.) Both films give little hints of what was about to happen to him, in this show and Dallas Buyers Club, but you can only see it coming with the benefit of hindsight.They aren’t quite the thunderclap that precedes the lightning bolt; more like the slight humming, a distinct brighter-than-the-day-before radiance, before a sun explodes.

As Rust Cohle, he’s really playing two characters. The first, a 1995 incarnation, is still and smart and wounded by life. In “Seeing Things,” we delve into his past as an deep-cover narco living on the toxic fringe of drug society. It was his retreat, ghost-like, after the death of his daughter in a traffic accident led to the dissolution of his marriage. It’s why he considers humanity a cesspool, and why when he speaks at all, he philosophizes about the selfishness of bringing more life into the world. He spends long stretches staring out the passenger window and soaking in the desolation of the Louisiana landscape, and years of drug use combined with PTSD leave him prone to hallucinations—luminescent auras from the street lights streaking past in bright contrails, a flock of birds forming into brief, prophetic shapes as they rise—that he must abide in a state of near-panic until they subside. But the violence of his past is never far behind; he smashes a mechanic’s head in with a toolbox to learn the location of a hillbilly trailer park brothel, and when Martin Hart (Woody Harrelson) grabs him by the lapels in anger after Cohle literally sniffs out his infidelity, the quiet man shows him how easy it would be to break his wrists.

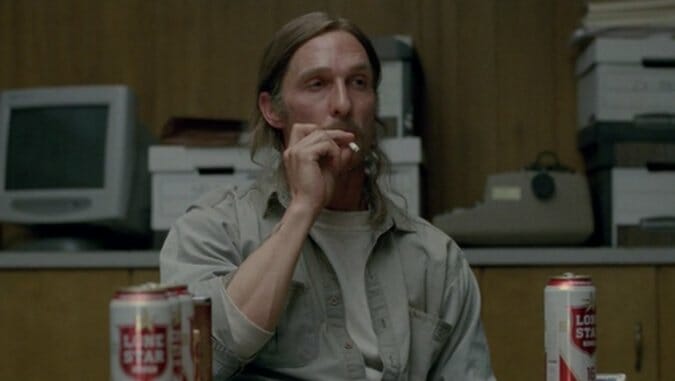

And there’s 2012 Rust. This is McConaughey in long hair, beat down by life, trying to convince himself and the detectives interviewing him that whatever state he finds himself in is a kind of “victory”; he knows himself, he says, after years of toil he has resolved that he’s a drunk living in the middle of nowhere, waiting for death. But the charisma of this man … this is where words begin to fail, if they haven’t already. McConaughey is almost too goddam massive for the screen. Watching him act, as latter-day Rust, is one of the most intense experiences I’ve ever had with TV. He’s beaten-down, but he can’t hide the life force that struggles to emerge. The medium can barely contain him; he belongs in a spaceship among alien beings. There’s something bursting out, and when he delivers certain lines—“start asking the right fucking questions,” for one—the experience is so visceral your own blood starts to pound. And Fukunaga, who, thank God, is directing all eight episodes, knows the weapon at his disposal. He lets the camera linger on Rust’s face at length, allowing McConaughey to dance from emotion to emotion with a word, with an expression. Working in tandem, they only need a moment to devastate.

As with the pilot, there are lots of hints in “Seeing Things” that Cohle is the serial killer who attaches deer antlers to his victims as some kind of fetishistic impulse. The detectives who have re-opened the case certainly think so; Cohle and Hart were meant to have caught the culprit years ago, but now the crime has reoccurred and nobody knows why or how. But there’s also the fact that Cohle seems to know things intuitively back in ’95; always a step ahead, like he’s following his own trail. He finds the “devil net,” he leads them to a burned-out church with hidden iconography, and he’s crazy enough, maybe, to do the thing himself. And didn’t he lose his daughter tragically? Couldn’t this be a recovery ritual?

They’re good red herrings, but red herrings anyway. It wasn’t Cohle; it’s more likely to be Hart (Hart is an old word for “stag,” by the way), but it’s probably not him either. Harrelson’s vitality may pale to McConaughey, but he’s pitch-perfect in his role as Hart, a man who presents a charming, good-ole-boy facade but whose marriage is crumbling and who isn’t quite the swaggering All-American he’d have us believe. As with Cohle, there’s a breakdown in his future, and the rebels are massing at the gates. He’s no upright foil, but his narrative inevitably looks mundane next to his partner’s strange, singular presence. Hart is the anti-hero to which we’ve become accustomed: flawed, smart, incisive, derelict. He knows how to charm people and stay on his feet, but he can’t help screwing up a family by fucking around and letting his masculinity run amok. If Cohle is celestial and almost psychotic in his damage, Hart is terrestrial, making the same mistakes men have made for centuries.

Harrelson deserves credit here, not only for his hard-gravel bearing, but for the fact that an actor with so much of his own inner magnetism is taking a back seat and playing a supporting role. There’s no sense of residual bitterness as McConaughey steals scene after scene, and no sense of overbearing pride as he creates the platform from which his partner can rise. Together, they’re perfect, and they’re practically exalted by a show whose visual language exceeds anything I’ve seen, including Breaking Bad. There’s the decimated horizon, for one, a character in its own right, stretching past in cane fields and billboards and trailer parks and all the poetic signposts of America in its last decades.

But even in containment, divorced from the sprawl of what passes for nature, the show excels. There’s an early scene where Cohle and Hart visit the victim’s mother, played by the wonderful Tess Harper, and here a series of shots tell us all we need to know about her life in the thrall of encroaching southern poverty. There’s a bowl full of prescription pills, an old TV with rabbit ears, a religious statue, and a snapshot of her daughter standing in front of men on horseback wearing KKK hoods. Finally, we see her fingers, ruined by years working with chemicals in a dry cleaning job. It would be tempting to say that the plot was driven by visual poetry, but that would be a disservice to the dialogue, which ranges from cynical monologizing to subtle reveals—“why wouldn’t a father bathe his daughter?” asks Harper’s character, shining a light on the abuse that led the girl to whatever vulnerabilities preceded her murder—and is even, at times, darkly funny.

We’re running out of space for this week, so I’d better cap myself before this segues into hysteria or fan fiction. The only excuse I have is that there hasn’t been a show this stirring in blank number of years, and I say “blank” because we’re only two episodes in and inserting the time period that’s truly in my head would make this review seem more lunatic and fawning than it already is. But what we can say for now, safely, is that it’s a mistake to think this show isn’t extraordinary just because its predecessors bear surface similarities. I could stand on my desk, grip a magic marker, and draw an angel on the ceiling, but it wouldn’t be the Sistine Chapel.