Tom King & Mitch Gerads Dissect the Muddy Aftermath of War in The Sheriff of Babylon

Tom King and Mitch Gerads’ The Sheriff of Babylon reveals its greatest conflict in its title. A cutting, meticulously considered snapshot of Iraq during the winter of 2004—two months after Saddam Hussein was captured during Operation Red Dawn—the 12-issue miniseries enmeshes a trio of protagonists in a clusterfuck of interests. The titular sheriff could be Chris—a tortured ex-cop training Iraqis to govern their freed homeland. Or it could be Sofia Al Aqani, a diplomat and contractor returned to her homeland from America to solve, often violently, the quagmire that’s grown over her birthplace. Nassir rounds out the human trio, a former cop under Hussein with some very dark secrets created under empathetic circumstances. Or it could be all three—or none at all.

An American symbol of cowboy diplomacy and binary morality, the sheriff is an antiquated concept on these battlefields. No villains or heroes exist in this historical fiction of tangled multilateralism; only good intentions that often lead down destructive paths. And it’s made for the best comic of the year so far.

King calls upon his experience as a former CIA agent who spent four and a half months in Baghdad, instilling a realism and sensitivity in every panel. Gerads, whose brother served in Iraq, matches that devotion with researched landscapes of vast highways and vacant diners. The city may stand as the most memorable character, a land perpetually promised relief that’s never received.

Paste spoke with the creators to discuss how much they’ve injected themselves into this tale, the effort taken to recapture the memory of Baghdad and the fluctuating truths of its reconstruction.

![]()

Paste: Tom, like protagonist Chris, you spent four months in Iraq and, in a previous interview, you mentioned that you feel a sense of cognitive dissonance over leaving Iraq when it was still in a state of flux. That sentiment mirrors some of the resentment Chris describes over feeling responsible over 9/11 in his drunken conversation with Fatima. How much of yourself is mirrored in Chris?

Tom King: I feel reflected in every character I write. It’s hard to say that one is closer to me than the other. I try not to push characters too close to myself because they get harder to write, but as a writer you try to find odd little personal experiences that you hope are universal, or think might be universal. I think one of those experiences is this odd guilt I felt after 9/11. Even though it was due to historical forces that are way beyond my control, I was responsible for it and had to pay the price for it— almost like our country was responsible for it and we had to pay the price for it. Not in an actual way, but just in a weird guilt way. Something big has happened and I have to change with it. And I put that guilt and response into Chris. When 9/11 happened, we all wanted to do something. Anything. That impulse might not be a good thing, because as Chris is finding out, his impulse to do good seems to lead down some dark paths.

Paste: And Sofia, her character and one liners are so stirring. What a strong, unique character. Where did she come from? Did you encounter any contractors like her?

King: She’s a combination of some very strong women over there who were put into positions of power you wouldn’t expect them to be in. But she also has a little bit of my wife in her, a little bit of my daughter and a little bit of myself, hopefully. And she also reflects…that hardness to her, and that toughness is something I found in all of these Iraqis who had gone away and spent the years outside trying to get back in, trying to fight Saddam any way they could. And they found themselves in this victorious position after the war.

I think a little bit of that bravado, that toughness—she has her flaws, too. She’s not a flawless character. And that bravado isn’t as strong as she thinks it is. And with those people who came back to the country saying, “I conquered this country, I understand it now,” I think Sofia is finding out she doesn’t understand it as well as she thought she did.

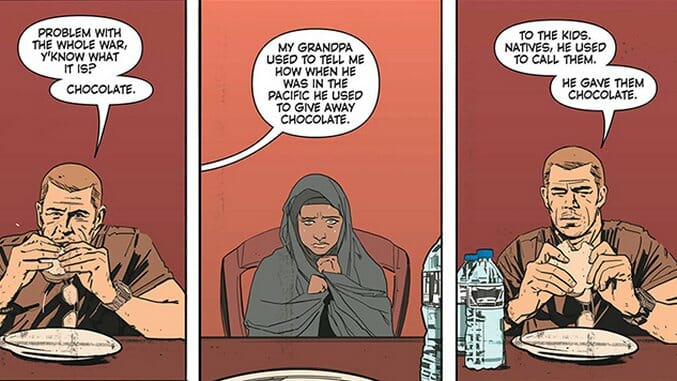

The Sheriff of Babylon Interior Art by Mitch Gerads

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-