Bojack Horseman: A Farce Of A Different Color

Bojack Horseman Makes An Effective Tragedy Because It's A Cartoon

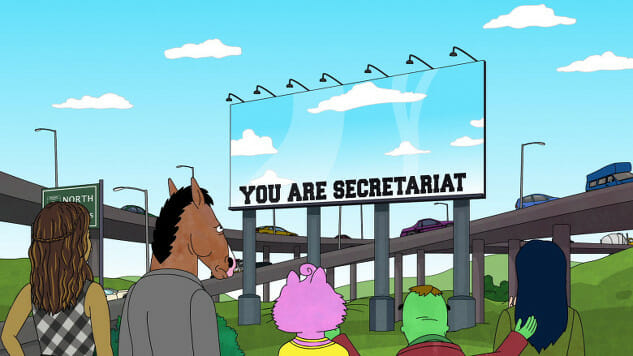

There’s something obviously comical about how critics are currently clambering over each other to offer the most glowing praise to Bojack Horseman. Clearly, they recognize how ludicrous that appears: Critics are being reduced to tears by Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s show, praising it as a “brilliant comedy about the human condition,” and a “character-rich treatise on depression,” but you’ll read few reviews that don’t also begin by highlighting Bojack’s on-paper ridiculous conceit. Bojack Horseman is an animated Hollywoo(d) satire set in an LA where humans and anthropomorphic animals live side-by-side. In season three, the title character – a depressed, middle-aged horse – has his eyes on the Best Actor Oscar, hoping to beat out the more starry likes of Jurj Clooners and Bread Poot. It’s a comedy, with animal puns, about our inability to be truly happy, and you’ll find near every ecstatic appraisal almost apologetically prefaced with a description that underlines the absurdity of it all.

Last year, Vox’s Todd VanDerWerff went out on a limb to declare Bojack Horseman a successor to Mad Men. High praise, but it’s true – the two shows similarly depict lost souls seeking happiness in a glam world where good feelings are ephemeral. But even VanDerWerff, acknowledging how bizarre it is that a show such as this one could be so deep, began his comparison with, “This might sound ridiculous, but….” We’ve all been culturally trained to think life’s big questions are to be dealt with by our live-action programs – preferably dramas – not animated comedies about alcoholic celebrity horses.

All the same, there are episodes in Bojack season three that are among the most profound, heartbreaking and ultimately creative that you’ll see this year. In daring to wade into waters that sitcom-style animation rarely (if ever) approaches, there’s a sense that Bob-Waksberg and co. are tapping a previously untapped well of ideas – and it’s resulting in some of the finest individual episodes of comedy-drama in recent memory.

Take The Bojack Horseman Show, a ‘period piece’ set in a parodically auto-tuned and carefree 2007 (background gags include a bank promising “Everything will be okay!”), and season three’s shattering penultimate episode, That’s Too Much, Man!. The latter finds Bojack and former screen daughter Sarah Lynn (Kristen Schaal, channelling every falling starlet of the 21st century) on a weeks-long bender, culminating in Sarah Lynn dying in Bojack’s arms from a heroin overdose. The episode is constantly punctuated by Bojack’s drugs and alcohol-fuelled blackouts, meaning we randomly skip minutes, hours and days ahead, a device that’s used for both comic and tragic purposes, Bojack’s increased loss of control over his own life a source of both hilarity and overwhelming melancholy.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-