10 Underrated Queer Books That Everyone Should Read

Every reader has a list of should-be-classics: works that speak to them but haven’t quite penetrated the wider canon. Often a novel or memoir or poetry collection is released to much fanfare but forgotten within a year, overshadowed by shinier bestsellers. In the (admittedly wide) field of queer literature in particular, so many tastemakers and gatekeepers favor particular experiences (white, affluent, cis, male, tragic, sexual) that books outside of those parameters are often enjoyed only by those who know where to look. The 10 books detailed below fall just outside of dominant queer lit circles, and they illuminate a range of experiences and imaginations beyond our most commonly told stories.

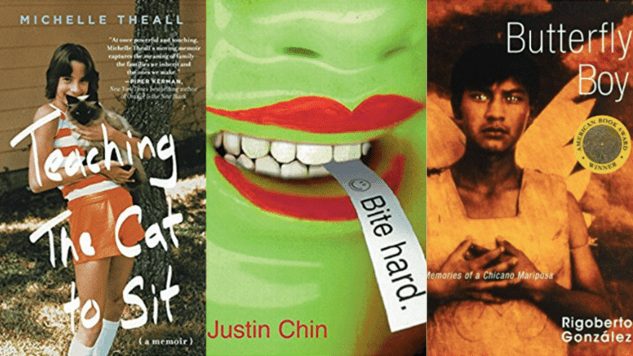

Asian-American poet, essayist and performer Justin Chin left us in 2015 following complications from a stroke, leaving both a tangible absence in queer writing and a substantial body of work behind him. Bite Hard, his first collection, established the themes he navigated throughout his work: frank discussions of sex, questioning of identities and intersections, reflection on what it means to be queer and Asian and Asian-American. In a literary scene dominated by white authors, Chin’s honest examinations of his own experiences, and the various ways in which supposedly liberating queer spaces still divide along other lines (race, age, body size and shape), have only become more relevant in the years since Bite Hard was first published.

2. Butterfly Boy: Memories of a Chicano Mariposa by Rigoberto González

2. Butterfly Boy: Memories of a Chicano Mariposa by Rigoberto González

“Mariposa” is the Spanish word for “butterfly,” but also a weaponized label akin to “faggot.” Rigoberto González’ memoir runs headlong into both definitions, charting a young, poor gay Chicano’s journey from turbulent childhood to self-accepting adult life. The field of queer memoir is heavily weighted toward the white, affluent experience (not to downplay the hardships of coming-out even in the WASPiest of families), which makes González’ experience, told in straightforward fashion, all the more illuminating. Like many young queer men, González experiments with cross-dressing and finds solace in vaguely homoerotic great writings, but he also contends with the constant motion of a migrant family, and the otherness of attending a predominantly white college where his peers seem to exist without a care in the world, making Butterfly Boy an important counterpoint to the dominant queer memoir.

3. Fair Play by Tove Jansson, translated by Thomas Teal

3. Fair Play by Tove Jansson, translated by Thomas Teal

How explicitly queer must a novel be to be labeled a “queer novel”? In Fair Play, Tove Jansson (known best for creating the internationally beloved Moomin characters) has crafted a beautifully moving portrait of a relationship between two older women, a writer and an artist, who have lived in connected apartments for decades. Although Jansson never makes clear that their relationship is a physical one, Mari and Jonna’s lives are as intertwined as two people might ever hope to experience, vacationing together, critiquing each other’s work and even battling jealousy when one half of the pair becomes close with a younger female intern. In true Finnish form, Fair Play isn’t structured around any grand dramas, but in the little moments and daily pleasures through which two people might hope to build a life.

4. Lord Dismiss Us by Michael Campbell

4. Lord Dismiss Us by Michael Campbell

Unsurprisingly, the expansive genre of British boarding-school stories never quite took off in America, where the tradition of gender-segregated private schooling was never common. Although many of these tales deal with the fun and foibles of same-sex romance between boys for whom girls aren’t presently an option—relationships treated as somewhat acceptable so long as they end at graduation—few juggle as many compelling characters and (utterly British) humor as Michael Campbell’s Lord Dismiss Us. Published just as homosexuality was decriminalized in Britain, Lord Dismiss Us most poignantly follows Carleton, a senior who hoped to graduate without indulging in anything “sinful,” who finds himself inexorably drawn to a younger boy. Complicating matters is both a new headmaster, who intends to bring the school up to muster, and Eric Ashley, a popular young teacher who catches feelings for Carleton. Campbell follows the structure of the school year to deliver both a humorous and, as is common for queer novels of the time, tragic ending.

5. The Man Who Fell in Love With the Moon by Tom Spanbauer

5. The Man Who Fell in Love With the Moon by Tom Spanbauer

Tom Spanbauer’s old-West epic plays with just about every toxically masculine trope of 1880’s frontier life you can imagine: narrator Shed is a “half-breed” bisexual boy who forms a makeshift family with town mayor/whorehouse mistress Ida, beautiful prostitute Alma, and rancher/lover/possible father Dellwood Barker. Spanbauer doesn’t shy away from hard truths of the era, from racism to a particularly brutal amputation, but his combination of raunchiness and Shed’s affecting search for his identity (not to mention unapologetic bisexuality) make The Man Who Fell in Love With the Moon a must-read for readers looking for a truly original, different sort of queer novel.

6. The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village by Samuel R. Delaney

6. The Motion of Light in Water: Sex and Science Fiction Writing in the East Village by Samuel R. Delaney

As in his monumental Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, sci-fi author Samuel R. Delaney breaks the bounds of memoir and confessional in the pages of The Motion of Light in Water, which details his early (open) marriage to a white woman, poet Marilyn Hacker, and his exploration of black gay manhood during the peak of New York’s downtown bohemian scene. Buoyed by a supportive partner as well as an anything-goes artistic scene, Delaney candidly recounts his sexual explorations alongside his writing process for his early breakthrough novels. Readers of Times Square Red, Times Square Blue will find the same detailed frankness in Delaney’s sexual encounters here, but a deeper look at navigating identity in a time and scene at once obsessed with breaking norms and held down by labels.

7. The Passion of New Eve by Angela Carter

7. The Passion of New Eve by Angela Carter

Angela Carter’s surreal sci-fi epic is as love-it-or-hate-it as they come. Readers should know upfront that The Passion of New Eve revolves around a male professor in a teetering-on-the-apocalypse future who is kidnapped by an enclave of women and transformed, working uterus and all, into the title’s “New Eve.” Carter, best known for her feminist retellings of fairy tales in The Bloody Chamber, would have difficulty publishing such a plot today, but The Passion of New Eve is less about claiming identity (or any sort of trans experience) as it is about the “battle of the sexes” and man’s inability to empathize with women. New Eve is a brief story—under 200 pages—but Carter wraps her sci-fi epic in the narrative and moral tidiness of a fairy tale, weaving her protagonist’s early sins into their eventual karmic conclusion.

8. The Sins of the Cities of the Plain by Anonymous, edited by Wolfram Setz

8. The Sins of the Cities of the Plain by Anonymous, edited by Wolfram Setz

No list of queer literature is complete without a bit of smut, and the infamous The Sins of the Cities of the Plain deserves more modern attention than it gets. First privately printed in 1881 and attributed to “Anonymous,” Sins is a salacious account of a male prostitute’s journey from boarding-school trysts to life in London’s thriving underground gay scene. Long considered a work that blends fact and fiction—protagonist Jack Saul is thought to be based on a notorious real-life hustler—Sins is as explicit as anything published today (some might even say “repetitive,” thanks to the sheer volume of sexual encounters documented), and weaves in real-world history related to the “obscenity” trials of the era. The late 1800s never seemed so raunchy.

9. The Swimming Pool Library by Alan Hollinghurst

9. The Swimming Pool Library by Alan Hollinghurst

Queer literature that deals with sexual promiscuity is frequently divided into pre- and post-AIDS crisis, as the way that queer men navigated sexual spaces was utterly changed by discovery of the virus. The Swimming Pool Library is distinctively “pre-,” as young protagonist William Beckwith springs from one sexual encounter to another with little concern for his actions or how they affect the men around him. With echoes of Maurice, both Beckwith and his elderly mentor Lord Nantwich seem to favor working-class men (and in Nantwich’s case, specifically black men), whether through unconscious desires or active pursuit of taboo. Like many early gay novels, there’s not much of a happy ending here, but for a look at pre-AIDS gay life in London and as a complement to better-known American novels like City of Night and Dancer from the Dance, The Swimming Pool Library is compelling reading.

10. Teaching the Cat to Sit by Michelle Theall

10. Teaching the Cat to Sit by Michelle Theall

Michelle Theall’s memoir about reconciling her sexuality with her family and with Catholicism hinges on an aspect of queer life that is too often overlooked by both memoir and fiction: coming out is typically a lifelong process, not a distinct event. For Theall, who faced ample discrimination in her conservative Texas town long before she even met another queer girl, moving away from home and having a child with her partner doesn’t whisk away all of her issues with family and faith. In seeking to have their child baptized, Theall and her partner are thrust into battle with the church and with Theall’s mother, placing Theall in the position to decide if it’s more important to be a good daughter or a good mother herself.

Steve Foxe writes comics, comics journalism and licensed children’s books. He is the editor of Paste Magazine’s comic section and lives in Queens, where he tweets about comics, horror movies, gay stuff and cats at @steve_foxe.