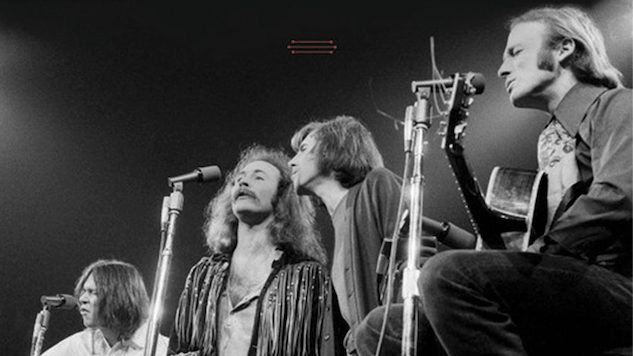

Two New Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young Biographies Trace the Band’s Fractious History

Graham Nash was on a helicopter with drummer Dallas Taylor flying into Bethel, N.Y., where their band was scheduled to perform at a festival. As they neared their destination, Taylor asked what lake they were flying over. It wasn’t water, the pilot replied. It was the audience.

The gig was Woodstock. The band was Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. The gathering on Max Yasgur’s farm would be their second-ever live performance, after recently solidifying a touring lineup with Neil Young, Taylor and bassist Greg Reeves. The weekend would prove to be a high point for the counterculture that Woodstock quickly came to represent—and for Crosby, Stills, Nash & (sometimes) Young, the ensemble that was in some ways the house band for the Woodstock generation.

“Their music and their image became indissolubly linked with the fate of the baby-boomer era,” music historian Peter Doggett writes in CSNY, one of two engaging biographies released this week tracing the band’s fractious history. The other is Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young by David Browne, a senior writer for Rolling Stone.

Browne covers the full arc of the band’s career, from its members’ musical origins in other groups in the ‘60s to the present. Doggett focuses on the musicians’ early lives and careers through 1974, when David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young toured together for the last time. Though both books cover some of the same ground, Doggett’s is far more detailed about the beginnings of the band and the musicians’ upbringings. Browne takes on the monumental task of summarizing a half-century’s worth of conflict, self-sabotage and, when the musicians managed to get out of their own way, music.

Browne covers the full arc of the band’s career, from its members’ musical origins in other groups in the ‘60s to the present. Doggett focuses on the musicians’ early lives and careers through 1974, when David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young toured together for the last time. Though both books cover some of the same ground, Doggett’s is far more detailed about the beginnings of the band and the musicians’ upbringings. Browne takes on the monumental task of summarizing a half-century’s worth of conflict, self-sabotage and, when the musicians managed to get out of their own way, music.

Crosby, Stills & Nash wasn’t intended to be a “band” at all, at least not in the late-‘60s sense of the word, which implied a specific identity, expectations and business commitments. Those things amounted to limitations, in the minds of Crosby, Stills and Nash, who had each dealt with all that in the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and the Hollies, respectively. They started singing together for the thrill of it, and they quickly realized that they harmonized with an uncommon purity that astonished their friends. That feeling of amazement carried over to the listening public when the trio released Crosby, Stills & Nash at the end of May 1969, thanks to songs including “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” “Long Time Gone” and “Helplessly Hoping.”

The singers intended CSN to be a sort of “mothership” situation that would, between group efforts, permit solo projects, outside collaborations and plenty of musical experimentation. Yet converting their “party trick” harmonies (Browne and Doggett both use the term) into something that certainly looked like a band, with a record deal and all the attendant obligations, quickly subsumed the idea of singing together for its own sake. If bringing in Young to help flesh out the songs onstage made sense from a musical standpoint, each book illustrates how adding a fourth massive ego also hastened the band’s descent into creative disputes and power struggles.

Though both authors admire the group and its songs, the musicians come off as intensely dislikable, especially as money and fame transform them. Stills is a taskmaster perfectionist with control issues. Crosby is a blowhard, a drug-addled hedonist with an attitude toward women that is startlingly chauvinistic, even for the era. Young, who had been part of Buffalo Springfield with Stills, is a cynical opportunist who sees joining CSN as a way to jumpstart his own then-lackluster career. Only Nash sometimes seems sympathetic; the most level-headed, he tries to act as a go-between among warring factions with limited success.

Though both authors admire the group and its songs, the musicians come off as intensely dislikable, especially as money and fame transform them. Stills is a taskmaster perfectionist with control issues. Crosby is a blowhard, a drug-addled hedonist with an attitude toward women that is startlingly chauvinistic, even for the era. Young, who had been part of Buffalo Springfield with Stills, is a cynical opportunist who sees joining CSN as a way to jumpstart his own then-lackluster career. Only Nash sometimes seems sympathetic; the most level-headed, he tries to act as a go-between among warring factions with limited success.

Together (and, just as often, separately), they cut a path through popular music in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Doggett writes vividly about the L.A. scene that produced Crosby, Stills & Nash, chronicling their interactions with Cass Elliot of the Mamas and the Papas, Peter Tork of the Monkees, Joni Mitchell (who was romantically involved with Crosby, then Nash), Judy Collins (whose relationship with Stills inspired “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes”), Jimi Hendrix, Atlantic Records impresario Ahmet Ertegun, David Geffen and more. Doggett does his best to tame the mythology of CSN, sorting through various stories and inconsistent recollections about when and where they first sang together (Was it at Elliot’s house, or Mitchell’s? The night the Hollies played the Whisky in February 1968, or sometime afterward?) and when various songs were written and recorded.

Browne in many ways has the harder task, as the band’s earlier years were its most thrilling and creatively rewarding. Surprisingly little of the music they made together still resonates; after their first two studio LPs, CSN and 1970’s Déjà Vu with Young, and the 1971 live album 4 Way Street, the Crosby, Stills, Nash (and Young) catalog is a study in diminishing returns. In the latter half of Browne’s book, there’s almost a numb inevitability to the musicians’ fumbling attempts in the ‘80s to contemporize their sound, Crosby’s ever-deeper descent into drug addiction that led to a stint in prison, and Young’s inability to stop dangling the possibility of a full-scale reunion in front of his bandmates, only to flake out nearly every time for inscrutable reasons of his own.

Taken together, CSNY and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young present as full a picture of the group as is ever likely to emerge. It’s not a triumphant story. Beneath the promise of those early songs—and that initial camaraderie—lurks a mostly unwritten, certainly unanswerable question that poses itself again and again: What if?

Much like the dream of the Woodstock generation, the tale of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young is awash in senseless vanity, squandered chances and potential left tragically unfulfilled. Yet it’s often hard to look away—just like with any car wreck.