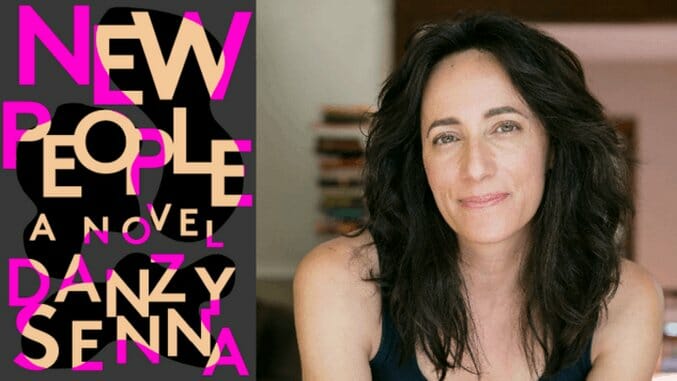

Danzy Senna Talks New People, Her Novel Exploring Race in ’90s Brooklyn

Author photo by Mara Casey

Danzy Senna’s latest novel sounds like a provocative conversation starter, but it actually continues a discussion that has been repeating for decades—if not longer. With its exploration of race and class, New People highlights the tension, ignorance and misperceptions that surround these divisive issues.

The award-winning author’s latest book is a darkly comic story with bite and brains, bringing late-‘90s Brooklyn bohemia to life through the eyes of Maria. She’s deep into the planning stages for her wedding to Khalil, who shares her “beige” skin color and matches her ambition. They both come from mixed-race parentage; as a couple they are “King and Queen of the Racially Nebulous Prom.”

But something is straining inside Maria. It may be the anxiety over a documentary film director coming into her and Khalil’s home, chronicling their engagement for a film about race and class titled New People. Or the strain might be from Maria’s consuming research for her dissertation, writing about cult leader Jim Jones and his attempt at a multicultural utopian community gone wrong.

Or, perhaps, the stress has sprung from a new temptation: a spoken-word artist whose radiance enchants her, inviting the specter of infidelity just before her wedding.

“There’re so many ways to read [Maria],” Senna says in a phone interview with Paste. “How much of it is because of her experiences with race? And how much of it is just an existential problem of being in the world? Or how much of it is that she has a strange relationship to her [adopted] mother? I wanted her to be complex and have a lot of different levels to her.”

Senna won the Stephen Crane Award for First Fiction and garnered early acclaim for her 1999 novel Caucasia, which followed multiracial sisters raised by a white mother and black father. But in New People, Maria, though multiracial, is socially categorized into one race because of a legal principle that only exists in the United States: the one-drop rule. It concludes that Maria is black due to the presence of “black blood” in her ancestry. Throughout the novel, she grows increasingly ponderous of the ways in which race, class, work and social status have influenced her identity.

But Senna has really left it up to the reader.

“Whatever interpretation you have of [Maria] is correct, as far as I’m concerned,” Senna says. “I’m the writer, and I don’t have any stake in telling the reader how to interpret or judge or diagnose her. It’s very much like I offer her up for your consumption. When I write, I try not to go into my character from a distanced or judging way; I try to fully inhabit her. I never want to be looking at a character from a bird’s-eye view; I want to be inside their skin.”

There’s clearly a lot is on Maria’s mind, though, as she falls into trance-like episodes of suspended judgment. This leads her into hilariously awkward yet profound encounters, like being mistaken for a nanny, being audited by a scientologist or getting away with some incontestable breaking and entering.

When writing Maria, Senna says that she didn’t feel “obligated to like her.” But the author wonders if the existential turmoil Maria deals with comes from her being “almost complicit in the problems of the world around her, and that the problems she rails against [are] a part of her.”

What’s fascinating about Senna’s book is that its characters are addressing issues of race and even the early signs of gentrification in a world 20 years in the past, before President Barack Obama, before Twitter, before Black Lives Matter.

“The conversation we’re having now [about race and class] are not new at all,” Senna says. “I was having the exact same conversations on campus in the early ‘90s, and we were talking about what would now be called intersectionality, or we’d be talking about what we called ‘whitey-ism,’ which is now called microaggression.”

“What I think is strange, for me, is that the conversation hasn’t really progressed. It’s like Groundhog Day, where you’re thinking: ‘Wait a minute…we’re still having this exact conversation?’”

Senna chose to write about Brooklyn in the ‘90s, because it’s the time and place in which she came into adulthood. The neighborhood where she grew up was diverse and working class, but she recently discovered that it’s now a whiter and wealthier area. Senna remembers witnessing the early signs of gentrification as a young adult, although she couldn’t categorize it at the time.

With this in mind, Senna has crafted a novel that proves invigorating in its contemplations of identity, while also infusing satirical and surreal humor into the narrative. What isn’t surreal are the character’s conversations—conversations that New People will hopefully advance by way of fictional drama.

“I don’t know what the central question of the book is,” Senna says. “But one of the things is that ‘black’ is not a biological category; it’s a cultural, political, economic category, formed by all those forces. I grew up to identify as black…I was of a different generation; that’s what you did, and out of that forms an identity. But, mostly, I was fascinated by the ‘90s in Brooklyn, and I wanted to write about that specific moment when I was there.”

Senna ultimately leaves New People up for your interpretation. So let the conversation continue.

Jeff Milo is a Detroit-based freelance writer who has covered books and music for Paste for several years. He reports on Michigan’s music scene for regional publications, as well as more unique features on his own website.