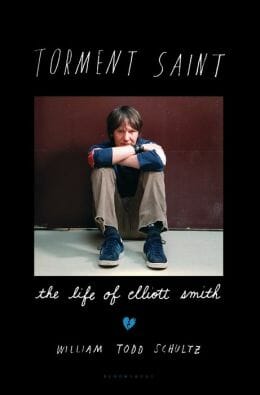

Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith by William Todd Schultz

Painmeister

William Todd Schultz’s Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith will likely go down as the definitive biography of the singer/songwriter, who died 10 years ago. Sympathetic but far from sentimental, Schultz paints Smith as a brilliant, uniquely talented man in free fall—producing some of the most important indie albums of the last 20 years while bearing severe depression and drug addiction.

You probably already know the story: Smith grew up in Texas and Portland, started Heatmiser at Hampshire College and broke out on his own during the mid-’90s in the Pacific Northwest. Abused by his stepfather in Texas, Smith suffered from depression throughout his adult life, even as he achieved an unexpected level of fame following a Best Song Oscar-nod for his contribution to the film Good Will Hunting, “Miss Misery.” The new millennium found Smith ingesting massive amounts of drugs, rarely performing and smoking what one estimate put at $1,500 of heroin and crack every day. In 2003, after getting clean and beginning work on a new album, he killed himself at his home in Los Angeles. He was 34.

Ardent fans will recognize many of the anecdotes in Torment Saint from other works on Smith, most notably Autumn de Wilde’s essential collection of photographs and interviews. But Schultz uncovers a great deal of new information that further humanizes the man who, in the decade since his suicide, has entered that weird genus of artists whose tragic deaths came to be seen as final artistic statements.

It’s fun to read about Smith playing basketball in middle school, or playing Sonic the Hedgehog obsessively as an adult. Viewed so often through the lens of his depression, Smith’s sunnier emotions—his humor and kindness—make you understand why the people around him endure so much pain through the darkest points of his life.

Smith almost becomes a different person when the darkness overtakes him. After a party in North Carolina in 1997, he bolted from a car and jumped off a cliff, apparently trying to kill himself. At the Crocodile Lounge in Seattle in 1998, Smith pulled friends aside, one by one, to tell them if he’s not around much longer, “remember I love you.” In a rare appearance at Sunset Junction in 2001, a gaunt Smith struggled to remember his own lyrics, aborting almost every song he started. “It would not surprise me if Elliott Smith ends up dead within a year,” a reporter wrote after a similar concert in Chicago the next year.

Schultz, a professor of psychology at Pacific University in Oregon, can be considered a leader in the field of psychobiography. His previous subjects include such cheery characters as Sylvia Plath, Diane Arbus and Truman Capote—a lot whose creative output seemed aligned with their personal suffering. The pain that gave life to their art also led, in various ways, to their deaths.

The tortured artist remains one of the most enduring stock characters in our cultural consciousness, though it’s unclear how much weight the stereotype deserves. Some studies demonstrate a correlation between creativity and mental illness. Others suggest people become their most creative in a positive mood.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-