Writers work at desks. They lecture in classrooms, retreat to workshops in peaceful settings. The world of loud and deadly machines seems far removed.

New England writer John Gardner, however, seemed cursed by machines. In 1945, just a boy on the family farm in upstate New York, Gardner sat at the wheel of a tractor that somehow dragged a cultivator over his younger brother, Gilbert, and killed him.

In 1982, another machine betrayed Gardner, age 49 and just a few weeks from his third marriage. His motorcycle didn’t quite make a curve in the highway near his home in Susquehanna County, Penn. The writer died in a ditch. The family buried his remains next to Gilbert near their childhood home.

Gardner clearly had better luck away from machinery, and he thankfully spent enough time at desks and in classrooms to fashion an illustrious career as a writer and writing teacher. With obsessive care, he poured himself into writing his books and teaching younger writers. After earning an M.A. and a Ph.D. at the famous fiction writer’s Valhalla, The University of Iowa, he became a champion of MFA students and a darling of writers’ conferences, especially Breadloaf, in Vermont.

He labored mightily to support the work of many promising young writers who came his way, including John Irving, Toni Morrison and Tim O’Brien. His well-known literary magazine, MSS, cultivated these and other gifted fictioneers, and in controversial books on writing, most famously On Moral Fiction, he forged a reputation as a literary pugilist. He took on John Updike and Thomas Pynchon, for example, challenging their work for falling short on purpose, for being a sort of parlor trick of literature.

One more thing—Gardner studied Anglo-Saxon literature, and published works on Chaucer and other old-timey writers.

I’m no psychologist, but it seems to me that as Gardner labored heroically at super-achievement, a monster lurked just offstage. I mean the monster of his younger brother’s death. That untimely surprise shadowed Gardner all his life. It’s the thing John Irving in The World According to Garp termed “The Undertoad”—the sudden, catastrophic event that gives the kaleidoscope of normal life a sharp twist and radically changes the picture, the relationships, the meanings.

I’m thinking Gardner wrote directly about this monster, in fact.

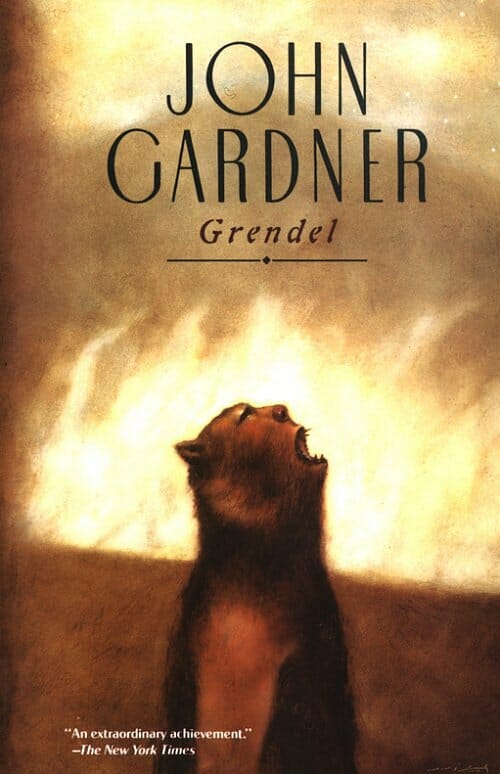

His most famous book, Grendel, recasts the story of Beowulf, the first superhero in English literature. If you’ll recall your Old English 101, Beowulf arrived on the shores of Denmark with a boatload of warriors to save the resident king Hrothgar from a terrible monster, Grendel, that slaughters subjects randomly and relentlessly.

Paste readers will likely be familiar with Beowulf’s saga, but here’s a synopsis. The hero confronts Grendel, sensationally rips the creature’s arm off his body and slays the beast, saving mankind…or at least a little Danish bit of it. Later, Beowulf does much the same to Grendel’s vengeful mother. (Readers may not remember so clearly the end of the 1,000-year-old saga; Beowulf fights a mighty dragon, slaying it but losing his own life.)

Gardner, in one of the most interesting and imaginative excursions of 1970s literature, recast the Beowulf story, twisting the kaleidoscope. How did Beowulf look from the monster’s point of view? Whoever considered Grendel’s side of the story?

Grendel published to critical acclaim in 1971. It remains today in the working vocabulary of most every serious writer.

Humans fascinate Grendel, it turns out, though they also repulse him. The monster holds a world view that is—well, monstrous—a fatalistic, nihilistic, solipsistic sneer of a philosophy. Fatalism marked many cultures of the Saxon age—the Vikings, for instance, believed that in the End Times, a great wolf came and ate up all the gods and destroyed Valhalla and that was that.

In Gardner’s book, Grendel may be utterly existential in his world view, but some grace still lives in him. Despite his best bad intentions, the monster can be pierced by music, the beauty of a queen, or even the crazed obsession and sheer power of a great hero.

To give you a flavor of the work, which can be sensationally horrifying, funny, profane and philosophical on a single page, read this excerpt, an early passage. Grendel describes the Danes in their mead hall, humans at a feast:

“They would listen to each other at the mead hall tables, their pinched, cunning rats’ faces picking like needles at the boaster’s words, the war falcons gazing down, black, from the rafters, and when one of them finished his raving threats, another would stand up and lift up his ram’s horn, or draw his sword, or sometimes both if he was very drunk, and he’d tell them what he planned to do. Now and then some trivial argument would break out, and one of them would kill another one, and all the others would detach themselves from the killer as neatly as blood clotting, and they’d consider the case and they’d either excuse him, for some reason, or else send him out to the forest to live by stealing from their outlying pens like a wounded fox. At times, I would try to befriend the exile, at other times I would try to ignore him, but they were treacherous. In the end, I had to eat them.”

Paste reader, we do love our monsters, don’t we? From Grendel, the original lizard king, to Godzilla, from Headless Horseman to haints in the woods, the human storytelling tradition twists and shouts with monsters and monstrous make-believes.

Sometimes we love monsters that turn out to not really be monsters at all, creations like Boo Radley. Sometimes we love monsters so much we turn them into cult heroes. (Freddie Kruger, anyone?) And look what we’ve made lately of vampires and zombies. Those poor living dead would be spinning in their graves, if they had any, over all the attention.

Why do we love scary monsters?

There’s likely a gene of fear ticking away inside most of us, beating like a shadow heart behind the human one. It’s not so much the monsters, per se, we fear…we actually tremble at the monstrousness of tragedy, at the unexpected, terrible lightning-strike moment of fate that takes away happiness and safety and comfort.

There may indeed be no atheists in a foxhole…but in a foxhole we most deeply believe in monsters too. John Gardner knew. He believed in monstrosity from that moment in his own past when the tractor lurched and a laughing little brother disappeared under the cultivator. The kaleidoscope turned; the Undertoad sucked away innocence. A bright sunny day on a farm suddenly became a lifelong horror.

The moment became a monster.

No wonder this Grendel of John Gardner’s feels so compelling. Oh, Grendel is a monster—nothing resembling sympathy or compassion glows in this thing’s heart. And yet…

Grendel spares the life of an old priest who seems confused and bedazzled confronting him. Grendel feels wonder when an old blind saga-singer strikes a harp in the mead hall and sings heroic stories. (As an aside here, Gardner’s parents gave him Saturdays off on the farm as a boy to listen to classical music in their home.) The bottom line: Grendel reasons—he thinks—and what kind of monsters are we, good Paste readers, who cannot find sympathy in any character able to weigh the contradictions and injustices and isolations of the world in the same ways we all do, one dark hour or another?

Don’t we all have some monstrousness to battle? That’s more or less Gardner’s point with Grendel. And how do we know beauty and perfection without the contrast of monstrosity?

Grendel even has language—human language, though far from lovely. Still…still…he speaks. He speaks to us.

Consider the close of the book. Grendel, his arm wrenched from the socket, torn completely off by a hero who could only be so fearless by besting something so fearsome…this Grendel staggers to the edge of a precipice. His final words:

I am weak from loss of blood. No one follows me now. I stumble again and with my one weak arm I cling to the huge twisted roots of an oak. I look down past stars to a terrifying darkness. I seem to recognize the place, but it’s impossible. “Accident,” I whisper. I will fall. I seem to desire the fall, and though I fight it with all my will I know in advance that I can’t win. Standing baffled, quaking with fear, three feet from the edge of a nightmare cliff, I find myself, incredibly, moving toward it. I look down, down, into bottomless blackness, feeling the dark power moving in me like an ocean current, some monster inside me, deep sea wonder, dread night monarch astir in his cave, moving me slowly to my voluntary tumble into death.

Again sight clears. I am slick with blood. I discover I no longer feel pain. Animals gather around me, enemies of old, to watch me die. I give them what I hope will appear a sheepish smile. My heart booms terror. Will the last of my life slide out if I let out breath? They watch with mindless, indifferent eyes, as calm and midnight black as the chasm below me.

Is it joy I feel?

They watch on, evil, incredibly stupid, enjoying my destruction.

“Poor Grendel’s had an accident,” I whisper. “So may you all.”

Poor Grendel’s had an accident. So DO we all, in the end. A tractor. A motorcycle. A respirator. A long sick bed. The Undertoad strikes. A lurking monster of a moment changes everything.

John Gardner knew Grendel like his own constantly trailing shadow.

So do we all.

Charles McNair authored the new novel Pickett’s Charge (have you read it yet?) and happily serves as Books Editor at Paste.