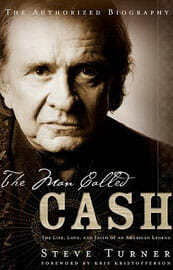

The Man Called Cash: The Life, Love…

As the authorized biography of the Man in Black, Steve Turner’s The Man Called Cash initially raised red flags for me. The unprecedented access Turner was given to Cash family members and to the vast Cash archives raised the specter of a whitewash. Just what was it that needed to be “authorized,” and by whom?

In Johnny Cash’s case, quite a bit. And to Turner’s credit, he doesn’t play the authorized game too well. In a deftly woven biography integrating the many strands of Cash’s complex, contradictory life, Turner portrays a Cash who is by turns generous, selfish, fickle and devoted to his wife, June Carter Cash, for 35 years; a foul-mouthed, hot-tempered, repentant saint; an addict; and a man of great strength and conviction. And always—a giant of American music.

By now the story is familiar, dusted off and resurrected as many times as Cash himself came back from the abyss and returned to musical greatness. Born at the Great Depression’s peak, raised in poverty, Cash found his authentic voice in Memphis in the early ’50s and never looked back. He was part of the great Sun Records stable of artists that included the young Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis, but he never fit tidily within the confines of rock ’n’ roll or rockabilly, and over the course of his 50-year career, he was equally at home as a seminal country artist; a rebel who identified with the outcast and downtrodden; a singer of folk protest songs; a television and movie star; and finally as an almost Job-like figure presiding over a disintegrating life with stark honesty and resolute faith.

Cash was, in short, as iconic a figure as American music has ever produced, and his life offers ample opportunity for mythmaking. Turner explodes a few of those myths—most notably the one that insists June turned Cash’s drug-addled life around—but also confirms a few others. Johnny was hell to live with at times—making June’s love for and commitment to him even more remarkable, and his drug addiction returned to haunt him (and her) long after country music’s first couple had made very public declarations of their Christian faith’s transforming power. But that same faith served as the bedrock foundation in Cash’s life, and as the source of hope for him at a time when everything he held dear—his health, his ability to make music, and finally June herself—was stripped away from him. Turner tells this story without sentimentality, but the circumstances create their own pathos, and the myth deepens.

Late in his life, Johnny Cash visited with U2 members Bono and Adam Clayton. He intoned a long and elaborate grace over supper, then opened his eyes, winked, and said, “Sure do miss the drugs, though.” Such was the enigma who was Johnny Cash, and Steve Turner captures the man in all his contradictory glory and weakness in this fine biography.

GET PASTE RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

The best music, movies, TV, books, comedy and more.