15 Books You Should Read to Understand Modern Journalism

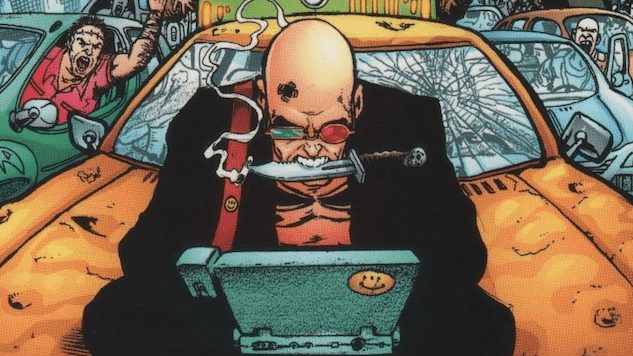

Art by Darick Robertson, Rodney Ramos and Nathan Eyring

Never has there been a greater need for media, and never has there been such a disjointed and disenchanting market for actual journalists. To make sense of our era, here is a chronological list of 15 books on modern journalism that everyone should read.

This list is not a how-to guide; there are plenty of books telling you how to indent or win the affection of the Associated Press. Nor is this a list of the most “important” or “worthwhile” books for the young journalist to read. This is a list of books to give you a sense of what is happening, why it’s happening and what might come next.

There will always be news fit to print. Whether we are fit to print it is a question left to us.

1. Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72 by Hunter S. Thompson (1973)

1. Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72 by Hunter S. Thompson (1973)

Hunter saw it coming. All of it.

The biggest cultural and social changes do more than just shift the ground; they alter our perspective and bend our minds. All of the boilerplate clichés of campaign books, movies and TV shows are boring for a reason: Thompson invented them. Read any serious campaign book published before Thompson’s 1972 rolling fusillade, and you’ll see what I mean. The old classics were documentary triumphs, but they were essentially technical manuals.

It was Thompson who gave the campaign an oracular tinge; Dante as rendered in Miami’s light. Thompson, the outside man in an outsider year (one that turned out to be an insider’s year, after all), stuck himself to the flailing place. A futurist text and a gravestone at once, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72 stands as the herald for the free-form fact-finding that would wash over every cranny of the American berserk in the next 40 years.

In this book, Thompson famously asked how low a man had to crawl to be President. The next century would find every possible way to answer that question.

2. All the President’s Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (1974)

2. All the President’s Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (1974)

Before Bernstein and Woodward broke The Big One, journalism was already well on its way to the trap of respectability. But Watergate sealed the deal.

Bernstein and Woodward turned a hustling, half-respectable profession into a kind of secular priesthood—and what an exorcism it was. All the President’s Men asks you to accept an absurd proposition: a sitting President was brought down by a collection of journalists pursuing a schmuck burglary. But that’s what happened. This is the prologue: the real story came after.

The Watergate story is the founding myth of modern journalism, and every post-’70s journalist is footnoting the old Nixon slaying. Even conservative journalists, who loathe the Washington Post, unconsciously ape the Watergate stories.

3. The Paper: The Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune by Richard Kluger and Phyllis Kluger (1986)

3. The Paper: The Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune by Richard Kluger and Phyllis Kluger (1986)

The roots of the New York Herald Tribune harken back to the founding of the Republic. Horace Greeley, who founded the Tribune, and James Gordon Bennett, who founded the Herald, hewed their respective publications into shape before the Civil War. The two dailies slugged it out for decades before fusing into a mega-brand in the early 20th century. More than any other American broadsheet, the Trib made newspaper scribbling into an art, if it ever was one.

It was known as the writers’ newspaper, and while we’re on the subject, it was the photographers’ newspaper, too. This mighty engine of news once strove with the New York Times for supremacy … and then it died by the mid-’60s. What killed the New York Herald Tribune? Bad business decisions. But why should poor choices have doomed a newspaper? It was a death by a thousand cuts—one of them necessarily fatal. Here’s the wilting away of newsprint, rendered as a social history. If you’ve ever wondered where the world of The Front Page went, here’s your answer.

4. The Corpse Had a Familiar Face: Covering Miami, America’s Hottest Beat by Edna Buchanan (1987)

4. The Corpse Had a Familiar Face: Covering Miami, America’s Hottest Beat by Edna Buchanan (1987)

“The crime that inevitably intrigues me most is murder. It’s so final.”

The Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Edna Buchanan is the greatest crime reporter who has ever lived. As a 1986 New Yorker profile noted: “Edna’s colleagues tend to speak of her not as a pal but as a phenomenon.” This book is her personal story, the narrative of Buchanan’s 18 years on the police beat for the Miami Herald.

Buchanan grew up in New Jersey, reading true crime stories. As an adult, she moved to Miami, where murder was on the rise. She would see 5,000 corpses during her time on the job. As she writes in these pages, “Many of the corpses have had familiar faces: cops and killers, politicians and prostitutes, doctors and lawyers. Some were my friends.” During the Florida drug war of the ‘80s, Buchanan led the pack, getting stories nobody else could, scoring interviews, digging deep for secrets, hammering away at the unjust and the unfair. Overcoming sexism, bias and the rough-and-tumble nature of the criminal world, Buchanan wrote story after story about the strange underworld of the Magic City.

“I am uncomfortable with unsolved mysteries,” Buchanan writes. But there’s no enigma about this book; it’s a master class.

5. Manufacturing Consent by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky (1988)

5. Manufacturing Consent by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky (1988)

Here it is, the Father of Contrarian Media Takes. If this is your first encounter with Chomsky and Herman, I’ll give you the TL;DR. Chomsky and Herman begin with the questions: Why does the media get so much reliably wrong? When we suck, why do we suck, and what is the mechanism of our suck?

The answer: Our media is constrained by the structure of our society. There’s no clique of censors, no elite group who sort our news, no conspiracy in rooms of high-backed chairs. Chomsky and Herman explain that in a free society (such as ours), governments can’t control what the media says. If you want to hold and retain power in a democracy, then you must shape public opinion.

Private ownership facilitates this process. The concentration of economic and broadcast power leads to group-think, which favors acceptable, mainstream opinion and marginalizes dissenting voices. Smaller platforms take their lead from larger ones; while this does not eliminate independent voices, it quiets them. A series of filters is created by this web of interacting forces. These filters shape an agreed-upon narrative which favors authority. The manufacture of consent, in other words. The result is general agreement without coercion … but just as damaging to a free society as the use of force.

If you read one book on this list, read this one.

6. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture by Stephen Duncombe (1997)

6. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture by Stephen Duncombe (1997)

Zines serve as a voice for marginalized people; they’re the purest form of alternative press. Although associated with punk rock and liberation movements, zines have been mouthpieces for the LGBTQ+ community, the African-American community and Native American communities.

In design, zines are the closest to the beginning of journalism: elaborated pamphlets that flew off of presses as soon as Gutenberg perfected printing. Notes from Underground is a comprehensive guide to the history of a splendid art form. Duncombe discusses how the modern American incarnation of zines were devised as newsletters for sci-fi fans in the early 20th century. As soon as the ‘60s got a hold of zine tech, all bets were off, and a multitude of new voices were in. At their heart, zines capture the dynamic nature of our society and provide a necessary counterbalance to the generic hum that is all too pervasive among modern American media. As Duncombe writes, zines are “an alternative fraught with contradictions and limitations … but also possibilities.”

7. Transmetropolitan by Warren Ellis and Darick Roberston (1997-2002)

7. Transmetropolitan by Warren Ellis and Darick Roberston (1997-2002)

This is the only comic book inclusion on this list, and it’s a necessary one. Transmetropolitan is the story of Spider Jerusalem, an outlaw member of the press roughly based on Hunter S. Thompson, Jerusalem writes for The Word, the largest newspaper in the urban center of 23rd century cyberpunk America. Eventually, there’s a Presidential election, and the wrong guy wins. Spider spends the rest of the series fighting the government.

That’s the through-line of story. What Transmetropolitan truly does reveal, through a series of short stories and Jerusalem rants, the importance of journalism and the strangeness of the people who practice it. The series captures what it feels like to be a reporter—not the factual bones, but the emotional core of being a striver in a bipolar, half-housebroken profession.

All hail the New Scum.

8.

8. 30: The Collapse of the Great America Newspaper by Charles M. Madigan (2007)

Every feature about journalism should contain someone shouting (or typing) the phrase, “Stop the presses!” So here’s the one for this piece: Stop the presses! Except, according to Madigan, the presses have already been stopped.

The American daily is on the decline and has been for some time. Newspaperdom is generally a nostalgic subject—we owe it to ourselves to be wary of reporters who wax too romantic on the subject. Madigan is in no danger of that here. Despite his obvious love for the subject, he’s clear-eyed on the topic of what happened. First on Madigan’s list: chain newspapers. Family firms used to own papers, and they were embedded in the community. That went the dinosaur way as soon as the great conglomerates went to work. When department stores shuttered, that also put the axe in, since advertising became less prevalent. And let’s not forget the role of sprawl, which knocked down the reach of the newsroom as cities deconcentrated. Madigan’s book is a story you’ve already heard, but detailed at such length, with ample verve, that it’s worth the read.

9. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organization by Clay Shirky (2008)

9. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organization by Clay Shirky (2008)

In his book, Shirky argues that digital technology gives us communication without hierarchy (it doesn’t, but let’s accept his argument for the moment). Shirky doesn’t broadside-endorse the new decentralized world; he simply sees the value of the new “adhocracy.” So how does Here Comes Everybody hold up a decade after its publication? Rather storm-weathered, I’m afraid. Shirky’s premises were disproved by the Egyptian revolution and the power of Facebook.

First, Egypt: In 2011, online media went agog when Twitter helped to overthrow the government in Cairo. But as documentarian Adam Curtis pointed out, that same government was soon restored to power. The so-called “Social Media Revolution” fell apart for the same reason Occupy Wall Street did. Without order, without shared purpose or structure, there can be no lasting change.

Second, Facebook: Look at the Internet of today. Instead of the open frontier we were promised by libertarian cyber-utopians, the Net is dominated by a handful of monopolies. The make-believe of free markets has been debunked. If the Twitter Revolution fell victim to the politics of the real world, then Internet freedom was swallowed up by the pitiless dictates of the market.

Why endorse Shirky’s discredited tome? For a simple reason. As of this writing, there is no single, definitive, popular work that tackles the possibilities of the decentralized media to come. We do not yet have the world Shirky discusses. It will not be given to us by corporations or by Shirky’s benevolent tech readership. But some day, the adhocracy will be real, and it will impact media first. We owe it to ourselves to consider what that world will be like.

10. Women in American Journalism: A New History by Jan Whitt (2008)

10. Women in American Journalism: A New History by Jan Whitt (2008)

Whitt began her career as a reporter in Texas and well understands the long, biased history of American media. “Too often, I realized” she writes, “I have considered the perspectives of women in journalism as ancillary to the great ideas originated by men, the great events driven by men, and the great newspapers owned and run by men…If that was true for me, how much more was it true for my students?” That was the seed, and this book is the result.

Whitt highlights marginalized women of the American press, from famous faces like Katherine Graham, Annie Laurie, Ida Tarbell and Nellie Bly to women who did incredible work outside of the mainstream press. Though they were often relegated to society pages (or encouraged, if at all, to write novels), women journalists have been writing for American newspapers since their inception. Under duress, under false names, under threat of firing or denial of sources, reporters endured hardship and scorn to bring the truth to their readers. Beginning with the Lowell Mill worker-newspapers of the 19th century and continuing to the tribunes of the alternative and lesbian press, Whitt illuminates the hallmark of journalism: It’s crucial to learn the whole story.

11. Shocking the Conscience: A Reporter’s Account of the Civil Rights Movement by Simeon Booker with Carol McCabe Booker (2013)

11. Shocking the Conscience: A Reporter’s Account of the Civil Rights Movement by Simeon Booker with Carol McCabe Booker (2013)

Jim Crow extended its tentacles into every aspect of American life, and that included media. Injustice—torture, lynchings, murders—could be ignored by the white press if it rarely made their front pages. But the time of change was coming, and one of the hallmarks of shift could be seen in African-American media. Ebony arrived on the scene 72 years ago, on the first day of November in 1945. Jet came soon after in 1951. And Simeon Saunders Booker was a stalwart of both publications.

Booker, the first African-American reporter for the Washington Post, saw it all. His date with immortality came when Booker covered the horrific murder of Emmett Till in 1955. “Nothing in either my upbringing or training,” Booker wrote, “prepared me for what I encountered on my first trip to Mississippi in April 1955.” Booker had experienced segregation in the border states, he wrote, but Southern discrimination was a different beast altogether. It was Booker who swore that lynchings would be covered outside of the African-American press; it was Booker who covered every important moment in the fight for Civil Rights; it was Booker who became the Washington Bureau chief for Jet, a position he would hold for 51 years. Shocking the Conscience is journalistic history as lived from the moment of creation.

12. Virtual Unreality: The New Era of Digital Deception by Charles Seife (2014)

12. Virtual Unreality: The New Era of Digital Deception by Charles Seife (2014)

Philosophy boils down to a pair of questions: What is real? And what do we know? Most of journalism consists of answering the second question, but Seife’s book is obsessed with answering the first. How do we know if something is real? “The Internet tells us.” But the Internet lies, and Seife catalogs the ways in which the online world can create the mirage of fact.

This book is far more than a list of hoaxes and half-truths; it reveals that creatures are shaped by their environment. In the West, human beings spend an ungodly amount of time online. What has that done to us? As the book notes from page one, digital information is nearly impossible to control, even when that data’s a straight-up lie.

Journalism ideally is the practice of truth, but the Internet has changed how we identify the truth. Seife explores what happens when consensus reality breaks down, when we continually ingest deception.

13. So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson (2015)

13. So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed by Jon Ronson (2015)

Why choose this book? The topic is online ostracism, not journalism. But this seminar on shaming is a shorthand account of how social media took on the role once played by the muckraking press. A large part of Ronson’s book, in fact, covers the strange life of the modern journalist.

The press business concerns public opinion. Journalists spread information to an audience to encourage, to inform, to titillate, to spur justice. That’s the goal; the result varies.

At its best, journalism abides by an agreed-upon set of behaviors. There are codes and rules of the road. It’s a fact of history that the technology of mass media came first, and the standards governing that media arrived later…when the dangers of misuse were clear. What would a world without the press look like? What will happen if the Fourth Estate truly dies and the Internet remains? Ronson’s book details the world to come unless we examine what the press has been, what it is and what it could be again.

14. The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992 by Tina Brown (2017)

14. The Vanity Fair Diaries: 1983-1992 by Tina Brown (2017)

Twenty-first century journalism has its roots in the ‘80s and ‘90s, when corporations began to swallow up media platforms. And nobody typifies that world better than Brown, the legendary editor of Vanity Fair and later the New Yorker. Her tenure in the magazine world is legendary, and this was the age when printed magazines were mega-profitable engines.

The Vanity Fair Diaries is a joy to read—like a P.G. Wodehouse comedy set in decadence-fueled New York with war criminal Henry Kissinger making regular appearances. Brown transformed the periodical into the chic imperial publication of the Reagan era, her tenure placing her in the running for greatest magazine editor of the 20th century, alongside Clay Felker of New York Magazine, Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone, Harold Ross of the New Yorker and Anna Wintour of Vogue. Brown’s rise to power and success represents the last great moment of the 20th-century magazine and heralds the long, slow decline of the print journalism to come.

15. Stranger: The Challenge of a Latino Immigrant in the Trump Era by Jorge Ramos (2018)

15. Stranger: The Challenge of a Latino Immigrant in the Trump Era by Jorge Ramos (2018)

This is the story of Ramos, a Univision anchorman and award-winning journalist, who was ejected from a Trump press conference in 2015. In short, Trump told him to “go back to Univision.”

That moment of cowardice and intolerance made Ramos ask crucial questions: What does it mean to be a Latino journalist in the age of fake news? And what does it mean to be, as Ramos puts it, “The Other” in America?

“When somebody hates you, you feel it across your entire body,” Ramos writes. “Trump started his path to the White House with a massive lie.” Ramos’ book, which is the story of Latinx journalism, works to understand how to move on from this moment. “I simply ask you to fight,” he writes at the end of the book, in a letter to his children, “to the extent that you can…if you noticed, I used the word ‘fight.’”

DISHONORABLE MENTION: Anything written by Tom Friedman (The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization, The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century, Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11 or any of his columns)

Friedman is a New York Times columnist who writes about globalization and foreign affairs in the laziest, most thoughtless way possible. If there’s an American-sponsored war, or a corporation moving a factory overseas, or a dull-eyed press flak burbling about exciting new developments in consumer IT, then Friedman will be there to sing its praises. Friedman is the kind of guy who asks the Saudi royal family about modernization and not about their murderous war in Yemen.

Friedman is the poster boy for the honest dangers of Media Success. So if you read his books, do the opposite of whatever he says.