Mark Synnott’s The Impossible Climb Reminds Us What It’s Like to Live on the Edge

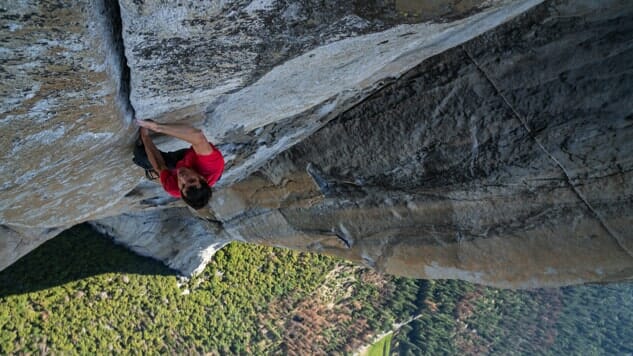

Photo from FREE SOLO, courtesy of National Geographic

I once lived on the periphery of people who edged up to the abyss—literally. The dive shop where I worked catered to the needs of technical divers, who by definition push the boundaries of scuba diving. And while I’ve never been as close to the edge as them—or the likes of Mark Synnott and the climbers he chronicles in The Impossible Climb—I do have a distant sense of the sublime blade on which they dance.

Perhaps most famous of those climbers is Alex Honnold, whose ascension—sans any safety equipment—up El Capitan’s mighty face was the subject of the Academy Award-winning documentary Free Solo. Synnott adds depth, intimacy and a hint of fear to Honnold’s climb; more importantly, he adds context to the historical feat.

Synnott, a professional climber himself, spends precious little time going into the existential aspects of the sport, and whether this is to the book’s detriment or merit depends on the reader’s appetite for inside baseball detailing of expeditions. Synnott’s cataloguing of thoughts and actions proves enough to catalyze tension, however, as he offers a celeritous ride along the chalk and blood history of the sport.

Synnott, a professional climber himself, spends precious little time going into the existential aspects of the sport, and whether this is to the book’s detriment or merit depends on the reader’s appetite for inside baseball detailing of expeditions. Synnott’s cataloguing of thoughts and actions proves enough to catalyze tension, however, as he offers a celeritous ride along the chalk and blood history of the sport.

Through first-hand accounts and thorough reporting, Synnott provides a vertiginous window into the world of climbers at the top of the sport. Sleeping in hanging bags, spending days and weeks on a vertical plane, speaking their own language, uncoiling lengths of muscle and rope—the climbers are seemingly beyond human. They are people so close to the edge that to fall off is, in some ways, inevitable.

The Impossible Climb’s athletes and technical divers both operate on a different plane than us, feeling the need to insert themselves into a world in which their very existence is forbidden by nature. Their motivations can seem inscrutable, even selfish. It’s the helicopter pilots, cutter crews and recovery parties who must put themselves at immense physical and psychological risk if something should go wrong; it’s the loved ones whose pain will linger long past a terrible reckoning.

And yet it’s easy for people to grasp the appeal of something like scuba diving: the ability to engage with marine life with an intimacy impossible to achieve from the surface; the chance to fly free of gravity’s cruel tyranny. To be surrounded by a prismatic cloud of reef fish is a vibrant dream many can appreciate; to witness a shipwreck materialize like a ghost in the gloaming is an obvious thrill.

What many do not understand without experiencing it firsthand is one of my favorite aspects of any activity that inches you towards the edge: the sharpness required to ensure one does not fall off. The focus begins on the surface and continues as you fall backwards, crashing through the thin membrane separating you from a place you do not belong. Before reaching any appreciable depth, you’re already trusting your partner, the crew and your gear while keeping keenly aware of the boat above you.

I’ve seen people panic, in the opaque Atlantic off South Carolina, the moment their eyes slip beneath the waves. Often trained in the crystal Caribbean, the blankness below them is too much. Their mind snaps—thankfully in a place where it is unlikely to be fatal (although the ladder has been known to poleaxe a diver who believes their full attention is no longer necessary in the sun).

The composure required to both enjoy a dive and to survive it demands the focus I often lack on the surface, where my emotions and insecurities can rage. Struggling is useless in a dive, because the water has already won. A fine balance is struck, where blade barracuda and alien tendrils of kelp take up as much of the mind as the time limit until you risk running out of air—the all-important gauge measuring how long you can survive.

It’s simple to strike this balance in the routine moments because it is requisite.

It’s when it must be earned that it can be transcendent.

Reading The Impossible Climb, I was reminded of a dive when—surrounded by water the color of sweet tea and without landmarks—I couldn’t tell if I was descending. As the final gasps of sunlight quickly surrendered and the world became black, I controlled my urge to bolt for the summer air. I made a home in the flashlight circle which comprised my entire world, a world of inches in which I would not be able to breathe.

I’d never felt so alive.

B. David Zarley is a freelance journalist, essayist and book/art critic based in Chicago. A former book critic for The Myrtle Beach Sun News, he is a contributing reporter to A Beautiful Perspective and has been seen in The Atlantic, Hazlitt, Jezebel, Chicago, Sports Illustrated, VICE Sports, Creators, Sports on Earth and New American Paintings, among numerous other publications. You can find him on Twitter or at his website.