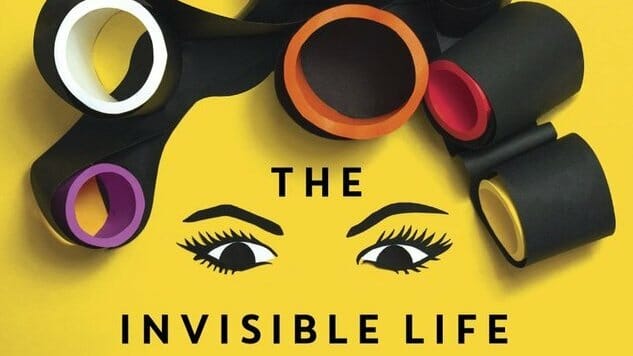

Women Steal the Spotlight in Martha Batalha’s The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao

Euridice Gusmao, the heroine of Martha Batalha’s debut novel, lives in a world far removed from the Greek myth evoked by her name. Euridice’s husband, Antenor, is no Orpheus; instead of a lute-playing poet pitied and admired by the gods, Antenor is a stubborn accountant at the Bank of Brazil, where he slowly rises through the ranks and into upper-class prosperity in mid 20th-century Rio de Janeiro. He can’t stand the sight of onions in his food, so he makes Euridice pluck the tiny pieces out of his bowl. “A single camouflaged piece in his beans,” Batalha writes, “left him queasy and belching the entire afternoon.” Worse, he thinks Euridice was unfaithful to him before their wedding night—a mistaken belief that he carries through decades of marriage.

But Batalha’s novel is not about Antenor or the novel’s other male characters. Their neediness and insecurities form a backdrop against which Euridice, whose status as a “housewife” relegates her to a constrained life, strives to define herself. In fact, the docile, quiet woman Antenor thought he had married is, in fact, “brilliant:”

But Batalha’s novel is not about Antenor or the novel’s other male characters. Their neediness and insecurities form a backdrop against which Euridice, whose status as a “housewife” relegates her to a constrained life, strives to define herself. In fact, the docile, quiet woman Antenor thought he had married is, in fact, “brilliant:”

Give her the proper equations and she would design bridges. Give her a laboratory and she would invent vaccines. Give her blank pages and she would write classics. But instead, she was given dirty underwear, which she washed quickly and left spotless, before sitting on the couch, looking at her nails, and thinking about what she ought to be thinking about.

Instead of taking place against a grand historical backdrop, The Invisible Life of Euridice Gusmao occupies intimate spaces. The narrator delves into the secret lives of nearly every character Euridice encounters; more than a few, including Zélia, the villainous neighborhood gossip, are granted full-blown flashbacks. This centering of even relatively minor characters to the narrative can feel distracting at times, but Batalha’s lively prose makes for enjoyable reading nonetheless.

Yes, the women of Euridice Gusmao cook and clean and feed their husbands and children, but they also teach and scrap and save and sew, breathe life into decrepit places, throw brilliant parties and run innovative businesses, make mistakes and make amends. They do all of this, Batalha reminds us, without an ounce of energy or much support from the men in their lives. Not that there is perfect solidarity among women, either: Dona Josefa, Euridice’s childhood teacher, is cruel and resentful of her pupil’s talents; Guida, Euridice’s long-lost sister, hides the grisliest details about the aftermath of her husband’s abandonment.

But the cumulative effect of the novel’s interwoven stories is a quiet celebration of the lives women lead away from men. Euridice’s hands and her mind, capable of fantastical creations, continually seek out new ambitions, each one a response and a challenge to her husband’s jealous narrow-mindedness. She finally focuses her attention on a typewriter, spending the novel’s final lines tapping out words for a book on the “history of invisibility,” a project that is itself rendered invisible by her family and newspaper editors’ indifference. Yet the novel’s final lines, representing the “tack-tack-tack” of the typewriter’s keys, suggest that Euridice, along with the other women in the novel, will end up having the final say.

(Editor’s Note: This reviewer is acquainted with Eric M.B. Becker, the novel’s translator.)

Lucas Iberico Lozada is Paste’s Assistant Books Editor. You can follow him on Twitter.