Let My Machine Talk to Me: Having An Emotion With Murderbot

My favorite definition of science fiction is purloined from William Gibson whose take goes a little something like this: Science fiction is the oven mitts with which we can begin to get a handle on the burning, red hot casserole of what we are each and all going through, the strange, new, radiating world of the right about now. This isn’t to say science fiction solves or gets to the bottom of it (“It” being the escalating weirdness within and without), but, with sci-fi, a mind-body like mine can hold its experience at a different angle. I know this feelingly. Science fiction can conjure a clearing. It’s a space-making enterprise. Science fiction helps.

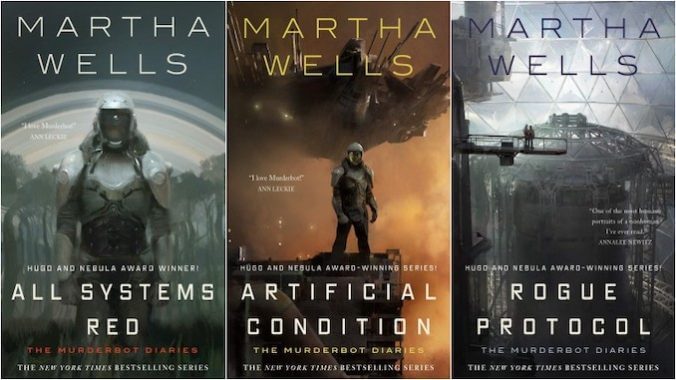

And in the long-range scan that is literature, we’ve never seen anything quite like Murderbot. I had no idea how badly I needed this brutally candid narrator composed of software, hardware, and cloned organic tissue in my life. First things first, Murderbot is not exactly “Murderbot.” The less dramatic moniker for the protagonist of Martha Wells’ Murderbot saga is “SecUnit” (short for “Security Unit”). “Murderbot,” however, is the sobering self-assessment SecUnit has affixed upon itself in view of the fact that killing quickly and efficiently to protect clients’ alleged interests is what SecUnit is designed to do.

There is a unique thrill in being made privy to SecUnit’s internal monologue as it negotiates its existence among crew members of spaceships engaged in planet hopping and trying to distinguish between hostiles and non-hostiles within and on the peripheries of an entity called “the company” (SecUnit’s manufacturer). But the larger drama is made up of the moments it’s drawn, mostly unwillingly, into interactions with others. Others being bots, constructs, humans, and augmented humans.

“It calls itself ‘Murderbot.’” That’s an augmented human, Gurathin, who, having accessed SecUnit’s internal feed through his interface implant, breaks the news to everyone within earshot.

SecUnit: “I opened my eyes and looked at him; I couldn’t stop myself. From their expressions, I knew everything I felt was showing in my face, and I hate that. I grated out, ‘That was private.’”

How did SecUnit achieve self-reflection capability? By hacking its governor module. In science fiction as in human development, this is where the action starts. SecUnit documents the assessments and realizations following this move starting on the first page of the first book in the series (All Systems Red). Assessment number one: Were it not for unlimited access to the combined feed of entertainment channels on company satellites (Rise and Fall of Sanctuary Moon being its preferred hundreds-of-episodes series), SecUnit would have become, from that moment forward, a mass murderer. Consuming media serves as a way of learning what trying to act natural might involve as well as an escape valve for feelings: “I hate having emotions about reality; I’d much rather have them about Sanctuary Moon.”

And from there—six books follow with a seventh, System Collapse, due out in November—we’re off! Off where? A long journey into, among other things, a theory of mind. The Murderbot saga is a rollicking and very often hilarious scrutinizing of feelings and thoughts, reactivity and responsibility, and the function of fear. That governor module, incidentally, for any and all SecUnits, administers pain as a motivator and as punishment in the event that a company construct fails to remain sufficiently obedient and on task. Its correction of the construct within which it is housed can even involve destroying it. Once hacked, however, a governor module can no longer circumscribe our rogue SecUnit’s powers of analysis. SecUnit describes the situation thusly: “Change is terrifying. Choices are terrifying. But having a thing in your head that kills you if you make a mistake is more terrifying.”

Apply that to your context and a cascade of associations—governor module equivalents like God, moms, dads, autocrats, coaches, bosses, bullies—might descend upon you. In the Murderbot diaries, there’s a personal journey that gives language to moral development that is also political liberation (Thinking, speaking, and acting freely). SecUnit testifies concerning the necessity of creative vigilance in what amounts to a psychic struggle “I was a thing before I was a person and if I’m not careful I could be a thing again.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-