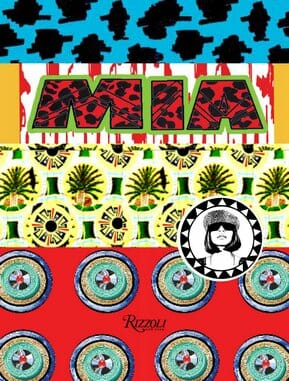

M.I.A. by Mathangi Maya Arulpragasam

The higher you go

The musician and artist M.I.A.’s new book, M.I.A., could be called an “artobiography.” It contains a few essays written by the author and a foreword from a friend, but it’s largely devoted to M.I.A.’s non-musical and pictorial art from 2005 to 2010.

M.I.A. calls the book “a document of the five years of M.I.A. art that spans across three LPs,” and this seems accurate. Though the LPs will likely serve as motivation for most readers to pick up this book, the music mostly provides a jumping-off point, something to be reconsidered in light of her visual work.

The reader first encounters the singer and artist as Maya, an aspiring filmmaker and photographer at a London art school in the late ‘90s. As Maya’s friend Steve Loveridge tells it, Maya spent most of her college career as a starving artist with a knack for making ends meet. She excelled at “shoplifting,” and “never bought Tube tickets.” Loveridge once asked Maya to steal him some food because he had none; the classy and generous Maya “came back with a bottle of Champagne and a tin of rice pudding.”

Maya’s parents were Tamils, members of the Sri Lankan minority group that engaged in a brutal war with the government for more than 20 years (the government claimed a final and bloody victory in 2009). The conflict politicized Maya; her cousin went MIA (missing in action) during the war. Influenced by the long brutal struggle, Maya began to feel that her fellow “students. . . were exploring apathy, dressing up. . . missing the whole point of art representing society.”

She managed to slip backstage at a concert and meet Justine Frischmann, a former member of the English band Suede. (At that time, Frischmann lead the group Elastica.) The musician soon invited Maya to live at her house, providing access to London’s in-crowd. Maya created some album artwork and music videos for Frischmann, while also interviewing, filming, and photographing the Tamil community in England and back in Sri Lanka. But a successful display of her work didn’t give her quite what she wanted; “dissatisfied with being a fine artist,” she moved into music, which allowed her to “represent society” to a larger audience.

As M.I.A., that’s exactly what has happened.

After just three albums—her first in 2005, her most recent in 2010—her career has already morphed through several stages. She exploded fast with her debut Arular, which takes its title, M.I.A. writes, “from my father’s code name. . . in the Tamil resistance movement.” At first an unknown quantity with great beats, style, attitude, and looks, M.I.A. and her music attracted unusual pop adjectives: chaotic, dense, amalgamated. Her songs tended to coalesce around momentum, a variety of electronic noises, rhythms, samples and percussion. It seemed to favor no musical genre over any other.

Her second release, Kala, achieved mainstream ubiquity on the strength of the song “Paper Planes,” which she performed nine months pregnant at the Grammys, accompanied by American hip-hop royalty.

Then the New York Times Magazine ran a piece that portrayed her as spoiled, impulsive, and unaware, a star spouting nonsensical radical sentiments while living the highest of high lives. (Do we see this kind of thing written about politically minded and similarly pampered male stars like Bruce Springsteen or Neil Young?) The piece also contained quotes from her ex-boyfriend and star producer Diplo, who said “She can’t really make music or art that well. . . She knows how to manipulate,” as well as statements by figures like the head of the Sri Lankan Democracy Forum suggesting her political statements were neither accurate nor helpful.

M.I.A.’s response? Strike back—she tweeted the writer’s phone number to the world, along with a message: “call me.”

The artist’s third album, ///Y/ (the title attempts an artful rendering of “Maya”), fared better on U.S. charts than her previous releases. But sounds strayed further from the visceral rhythms that won her fans in the first place, and reviews came back mixed. YouTube removed a nine-minute video in support of her single, “Born Free,” almost as soon as it appeared—the film portrayed systematic executions. Then M.I.A. gave the world the finger during the Super Bowl halftime show. . . though she apologized the next day.