Introducing Endless Mode: A New Games & Anime Site from Paste

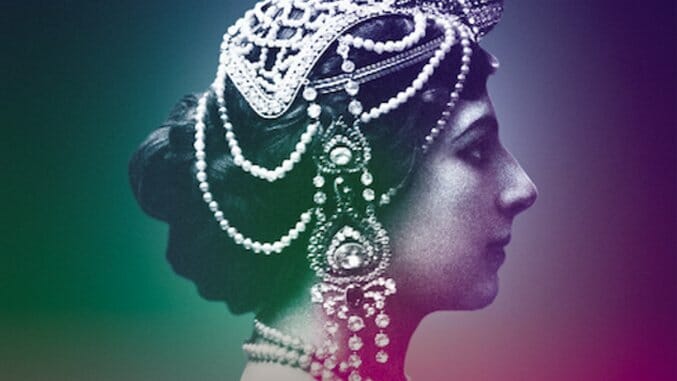

In the near century since her death, Mata Hari has become more of a legend than a historical figure. The Dutch-born exotic dancer, who rose to fame during Paris’ Belle Époque of the early 20th century, crafted a glamorous and near-mythic identity for herself. But in Paulo Coelho’s latest novel, The Spy, the author highlights Mata Hari’s humanity to reveal a flawed woman whose desire for freedom led to her execution.

Mata Hari was born Margaretha Zelle in 1876 in Holland, where she grew up and studied to be a kindergarten teacher. But Zelle was eager for adventure, and at the age of 18 she responded to a personal ad listed by Rudolf MacLeod, an officer stationed in Indonesia. They married soon after, and she traveled with him to Indonesia where she began studying local dances. But MacLeod proved an abusive and demanding man, and following the death of their second child, they returned to Amsterdam and divorced. This enabled Zelle to move to Paris in 1903, where she performed burlesque-style exotic dances under the name Mata Hari.

By 1905, she was a star.

By 1905, she was a star.

Twelve years later, she was executed by firing squad as a German spy.

Coelho lays out these facts via two letters: Mata Hari’s letter to her lawyer, recounting her life story and assuring him that she will soon be free; and her lawyer’s letter, written with the knowledge that Mata Hari will be executed the following morning. Neither believe their letters will ever be read by their intended recipient, a twist that adds an air of desperation to Mata Hari’s words and a desire for absolution to the lawyer’s.

Coelho’s prose brings Mata Hari to life as a deeply flawed woman who views her sexuality as a means to gain power and favor. She references her influential friends throughout her letter, listing men who could now use their position to secure her freedom. But she fails to recognize that her own power is easily demonized and that her very reputation as a sensual woman can be used to denigrate her character.

The lawyer’s letter adds another layer of sadness to the already heartbreaking narrative woven by Mata Hari. He outlines the espionage case against her, as she was a double agent recruited by the Germans but loyal to France. She became a victim of a system looking for a scapegoat, and Ladoux, the officer to whom she reported, was not willing to let a lack of evidence against her lessen the severity of his accusations.

Mata Hari behaved recklessly, traveling across the continent to play officials off of one another. She had an inflated sense of her own power, one that the men in her life were willing to indulge so long as she provided them with what they wanted—be it state secrets or a night in her bed. When those who could sway the verdict for her could have made a difference, they lined up to deny her; even a soldier Mata Hari had loved claimed he used her as a nurse with no real affection.

This is the tragedy of The Spy. Rather than relying on romanticized notions of sexuality and wartime intrigue, Coelho rests the novel’s drama in Mata Hari’s efforts to secure her impossible freedom. Her desire to escape the constraints of her childhood, her marriage, and her imprisonment was denied by men at every turn. Despite her strength and ingenuity, Mata Hari was a woman in a time when her independence relied on the favor of men—men who proved too fickle to defend her life.

The fact that Mata Hari was executed is established within the novel’s first pages. But as her story nears its conclusion, it’s clear that it couldn’t have ended any other way. Despite her best efforts, Mata Hari was vulnerable to the whims of the men she trusted.

With The Spy, Coelho has created a portrait of an anachronistic woman who was destroyed by her times and became a legend.

By 1905, she was a star.

By 1905, she was a star.