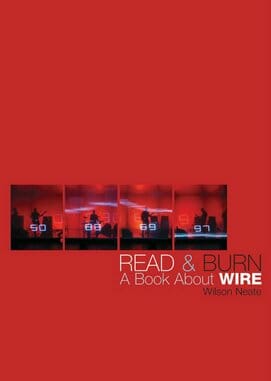

Read & Burn: A Book About Wire starts with a list:

This book was not read, vetted, or approved by Wire…

This book is not a biography of Wire…

This book is about the band-members’ solo project

This book does not forensically dissect each of Wire’s albums This book does not mention every Wire song…

This book does not provide a complete discography…

This book does not compile or comprehensively analyze press coverage

It’s an odd way of kicking things off, and it may leave the reader wondering—what didn’t author Wilson Neate rule out? Perhaps the book contains a series of haikus based on Wire song titles? Or maybe a two-man play using Wire’s lyrics as dialogue—one actor does his laundry, repeating the phrase, “I’ve got you in a corner,” while the other actor softly mumbles “Next week will fix your problems” (both lines from Wire’s debut album).

But Read & Burn contains no haiku, no playwriting. Neate—who also crafted the 33 1/3 series’ entry on Wire’s first album—combines most of the things that he says his book is not…into what it is, a detailed and straightforward examination of the men in the band Wire and the music they made. There’s some biography, some forensics, a lot of songs, plenty of discography, interviews and a generous helping of press coverage.

English art school boys Colin Newman, Bruce Gilbert, Robert Grey and Graham Lewis released their debut full-length as Wire in 1977, not long after punk exploded in England with the Sex Pistols and The Clash. The group’s first three albums attracted many admirers, on both sides of the Atlantic: Big Black, REM, Throbbing Gristle, My Bloody Valentine, Minutemen (whose Mike Watt wrote this book’s foreword) and Elastica have all covered Wire songs or vocalized appreciation for the band.

The critic Sasha Frere-Jones even went so far as to write that, “[i]f art-pop is a thing (probable) and the Beatles invented it (pretty sure), then Wire did it better. . . than anybody,” which is of course a ludicrously provocative statement. But the band has many dedicated fans—probably the target audience for Neate’s opening barrage of disavowals.

According to Wire’s own Newman, the band’s debut album attempted “to give punk rock a good kicking.” Or as Lewis notes, the record operated “against what exists.” What Wire set out to be against included the bluesy, R&B base of rock, as well as its “cheerfulness and looseness.” Also, the group wanted to demonstrate that punk had (already in 1977) stagnated and solidified into a restrictive orthodoxy, instead of functioning as a force that spurred innovation and experimentation.

Although Neate points out (again and again and again) that Wire still used punk’s language at this point in its career, Pink Flag worked to cut away any extraneous elements from music. “No solos; no decoration; when the words run out, it stops; we don’t chorus out; no rocking out; keep it to the point; no Americanisms.” The album’s a streamlined series of short, sharp, guitar-driven tracks, full of points, dots, dashes and fuzz.

The band made its next two albums different. For the second, Chairs Missing, “‘[t]here was a definite shift of emphasis to slightly stranger areas. . . using effects rather than thrashing away’” and using the studio itself to warp and manipulate instruments, leaving behind the bare-bones rock lineup and uncaging its sound. “Keyboards were used to create atmosphere” and “to get beyond the limitations of guitars.” Songs came “slower and more developed.”

With 154, the third album, Wire started careening “in all kinds of directions” as the visions of the group’s members diverged. Taking the process behind Chairs Missing even further, the band “intensified focus on the possibilities opened up by the recording environment and its tools.” Effects pedals served “not just as the starting point for a track—as the source of an interesting random noise—but also as tools with which to engage in the continuing development of pieces.” Wire even did some “proto-sampling” by looping a percussion track.

Despite increasing tension, the gang seemed to agree they were shooting for “an integrated electric sound which didn’t have an obvious source.” A sound that had started as a reaction (albeit one unable to break away from the initial action) now stood as something very much its own—seemingly source-less, technological and modern, unique.

The band had always taken an anti-commercial stance, usually refusing to play hits at promotional events, instead playing unrecorded and experimental material. When promoting its third album, Wire took things even further, putting together a theatrical performance that included “separate artistic interventions”—in diverse media—by each band member. Gilbert executed a performance titled ‘Tableau,’ which consisted of him pushing a trolley with a glass on it around the stage; a stagehand would periodically fill the glass, with Gilbert pausing to drink from it.” Notes accompanying the performance proved highly illuminating: “Change cannot exist without non-change. Non-change does not exist. Therefore change does not exist. What is repetition?”

Neate seems to support the band’s efforts to be willfully different, though the press didn’t feel the same way (terms like pretentious have been applied). Wire’s label EMI parted ways with the band not long after its theatricality began. (It should be noted that Wire’s lack of commercial success wasn’t entirely its fault. The band wanted to make a video for one of its songs, but its “ideas were rejected by EMI’s marketing experts, who assured them. . . that there was no potential in music videos.” Whoops!)

Wire also went on its first hiatus at this point. Gilbert’s idea for the next album: “… everyone should go home and make an instrument. . . without knowing what everybody else was doing, we’d go into a rehearsal room and make a noise.” Newman’s thoughts: “I didn’t really understand what kind of record he wanted to make.” So they took a break and pursued solo projects. Wire recorded together again in the late ‘80s, and it released albums intermittently since then, with the latest, Change Becomes Us, out a few months ago. (Neate follows the band’s developments through 2012.)

Even in the late ‘70s, before the Internet and social media, trends in pop music flamed quickly and burned out more quickly. Punk took over the world; not long after, the Sex Pistols imploded, and The Clash moved on to more expansive sounds.

But Wire didn’t end up as just another second-wave punk band. Plenty of English rockers did, and most of them aren’t the subject of books.

Some groups achieve success by starting a movement, or by jumping on the bandwagon just as a new sound or form develops. Wire’s early work shows that the opposite approach also matters: Choosing to define your art against a trend and working diligently to escape the structures inspired by an artistic movement can be an effective strategy for creating new and vital material. (Or, as Wire would say, “Change cannot exist without non-change.”) The strategy also helps grab the attention of the press and possible buyers of albums.

Next for Neate? Hopefully the haikus or the two-man play. Go ahead and read…but there’s not much reason here to burn. Neate takes a pretty conventional approach to a band that made its name synonymous with actively ignoring convention.

Elias Leight is getting a Ph.D. at Princeton in politics. He is from Northampton, Massachusetts, and writes about music at signothetimesblog.