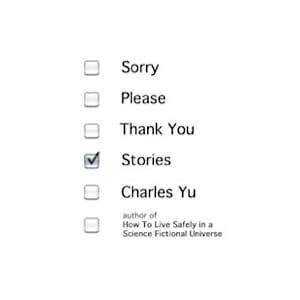

Sorry, Please, Thank You: Stories

Something Yu under the sun…:

And for the first time since the quest began, I start to feel a little wobbly, as if my POV isn’t so stable. As if the center of things is moving. As if the frame is unsure of who to follow, whose story it is. As if, maybe, I’m not so destined for my destiny after all. —Charles Yu, from “Hero Absorbs Major Damage”

Literature always progresses, evolves, devolves—whatever the case, it changes immensely. A shift in the ideology of literature that began in the late 1960s still resonates loudly in what we read and write today.

In 1967, John Barth wrote “The Literature of Exhaustion,” an influential essay that spoke of literary apocalypse. Why? Because, Barth said in sum, every story had already been written. All new literature would be referential in nature. All new literature was literature of the past. This was and is postmodernism—a term we use widely but that few, if any, can ever really define.

This abridged postmodern literature lesson leads us, for a moment at least, to a new collection of fiction by Charles Yu. Sorry, Please, Thank You employs metafiction, a self-reflective, self-referential form that draws attention to itself not only as art but as story attempting to contain ‘truth.’ Yu’s book certainly looks contemporary. It certainly has a contemporary-sounding title. And, in my view, it certainly provides us with work that begins to deconstruct the literature of exhaustion.

It’s the third book from Yu, a lawyer currently living with his family in Santa Monica, Calif. His 2010 novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fiction Universe made him a runner up for the Campbell Memorial Award, a distinction given to the year’s best science fiction novel. Additionally, the National Book Foundation recognized Yu as one of its “5 under 35” fiction writers of the future to watch. (Former National Book Award winner Richard Powers nominated Yu.)

With this collection, steeped in originality, we get echoes of David Foster Wallace’s early collection, Girl with the Curious Hair. Like Wallace, Yu abandons the more self-serving, insular metafiction of the past 40 years for a fresher form. Using technology, pop culture, etc., he attempts to write fiction that can be best shared with readers, not just critics or scholars.

Yu, in fact, marries science and literature. This affinity stands abundantly clear in the collection’s opening piece, “Standard Loneliness Package.” Set in the not-so-distant future, the story follows an employee for an overseas company with a stirring slogan: “Don’t feel like having a bad day? Let us have it for you.” Our protagonist earns $12 per hour to feel other people’s pain, sorrow, guilt, or grief. “For a price,” he states, “almost any part of life could be avoided.”

It’s a quirky, original piece, yet deeply emotional and in many ways all too real. Yu touches on how, for too many of us, the only break from our job, our cubicle, comes when life causes us the most pain. Besides those moments, we just live the daily grind.

Yu’s character does his empathic work very literally:

“I am at a funeral.

I am losing someone to cancer.

I am coping with something vague.

I am at a funeral.

I am at a funeral.

I am at a funeral.

Fourteen tickets today in twelve hours. Four half hours and ten full. On my way out, I can hear someone wailing and gnashing his teeth in his cubicle.”

We witness emotion as a corporatized value—an itemized, exchanged, commodity, traded and processed. This dehumanized look at life ironically reveals the very humanity in it all.

“I am feeling that feeling. The one that these people get a lot, near the end of a funeral service. These sad and pretty people. It’s a big feeling. Different operators have different ways to describe it. For me, it feels something like a huge boot. Huge, like it fills up the whole sky, the whole galaxy, all of space. Some kind of infinite foot. And it’s stepping on me. The infinite foot is stepping on my chest.”