Ivan lived alone. Big and rumpled, his hair a tangled mess. Time and worry, but never the sun, marked his face. Even in old age he remained powerful, nothing but muscles and a strong back. Reminders of a life lived behind bars.

His incarceration—nearly three decades of solitary confinement—affected his personality, too. After his release he couldn’t get along with other males. He craved females but never understood them. Not surprisingly he chose a flirtatious mate, a woman who, because of her own secrets, could never be his alone. Maybe that’s why he sought her out. Maybe, as women sometimes do, she sought him out for his imperfect strength, as someone broken, in need of fixing.

Ivan’s extraordinary life spanned two continents, first Africa then America. His life always drew attention and admiration as no ordinary man could. There lay his problem. He was in fact not a man at all but a great ape, a western lowland gorilla. This ironic duality—as a man he never would’ve been imprisoned, but only as an ape could he have been so loved—determined the trajectory of Ivan’s life and continues, even after his death, to shape his legacy.

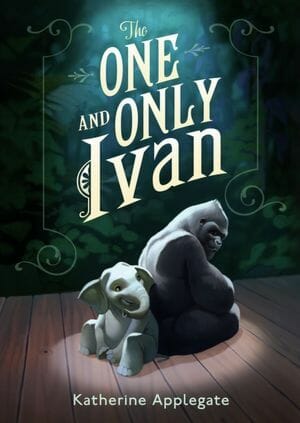

That legacy, and its accompanying myths and mystique, grew this year when Katherine Applegate’s The One and Only Ivan—a fictionalized autobiography of this iconic and long-suffering primate—won the Newbery Medal for distinguished contribution to children’s literature.

Though ostensibly for children, the 300-page book proves well worth the single sitting required to read it. Applegate’s spare writing and gutting topic—less the capture and detention of wild animals than our own culpability, as an audience, for the myriad ways they are mistreated—command attention.

Take the following passage, which appears early as Ivan considers not only about his own predicament but also the people who show up to bang on the glass…and who, in his opinion, talk far too much about far too little:

I know this is troubling.

I too find it hard to believe there is a connection across time and space, linking me to a race of ill-mannered clowns.

Chimps, there’s no excuse for them.

Time and again Applegate’s wit and her dry, clipped and deliberate pacing drag you straight to an obvious conclusion…only to yank the rug from under your feet. Her writing, at once poetic and concise, delicately wraps even the thorniest of issues in lyricism. Note the seamless transition from indictment of class to a treatise on mortality:

Inches away, humans flatten their little hands against the wall of glass that separates us.

The glass says you are this and we are that and that is how it will always be.

Humans leave their fingerprints behind, sticky with candy, slick with sweat. Each night a weary man comes to wipe them away.

Sometimes I press my nose against the glass. My noseprint, like your fingerprint, is the first and last and only one.

The man wipes the glass and then I am gone.

Gone, the one thing Ivan—in life as in death—could never be.

In 1962 Ivan’s mother gave birth to twins in the jungles of Zaire. Two years later, animal traders captured Ivan and his twin sister and shipped them, along with five other gorillas, to the US. Only Ivan survived the transit. His new life, his American life, started in Tacoma, Wash. He lived with a human family until he did what gorillas do—he grew. Grew too big, too rambunctious, too not-human. So he moved again, this time to Tacoma’s B & I Shopping Mall, where he spent the next 27 years in a 14’x14’ glass and concrete enclosure.

He quickly became Tacoma’s most famous resident, existing on hamburgers and cigarettes. He took up finger-painting. He watched TV. By all accounts he interacted with visitors. He looked healthy, happy even…for a time. Time changes all things, even for a gorilla whose concrete roof forbids the sun to rise. Ivan grew sullen, inactive, bored.

The world outside changed too.

By the mid-1980s, experts abandoned the old view of zoos as nothing more than places for a curious public to ogle captive animals. They promoted realistic habitats, natural diets and communal rather than solitary living—in short, many things an animal needs to be both physically and mentally healthy.

Perhaps no ape better captured this nascent movement than Zoo Atlanta’s Willie B.

Willie arrived in Atlanta in the 1960s and for decades he lived alone in a tile and glass enclosure. Few people thought much about Willie until photos surfaced that showed off his deplorable living conditions. The pictures showed an ape with a deep…and deepening…depression. Atlanta, scandalized, responded. The city raised not just awareness but money, and in 1988 Willie moved into the newly created Ford African Rain Forest. Willie’s success and the very public outrage over his treatment jolted the West Coast’s fledgling animal rights movement into action.

A Seattle-based group called the Progressive Animal Welfare Society, PAWS, began picketing the B & I Shopping Mall. As Ivan’s notoriety grew, so did comparisons between Willie’s new, outdoor habitat and Ivan’s shopping mall cage. National Geographic made a documentary on these two apes—roughly the same age, of the same species—and of their incongruous lives.

This was the 1980s. PETA toddled along, only a few years old, and Avon wouldn’t stop testing its products on animals until 1989. Despite outrage, Ivan remained in his cage. People continued to stare.

At this point in Ivan’s real-life story, Applegate began inventing his fictional one. After reading about him in the New York Times she knew instantly she’d found a subject worthy of a book.

Fittingly, her narrative begins at this intersection of an indifferent past and a slowly awakening future. Applegate’s Ivan lives with his eyes only half-open, willfully forgetting his past. He can’t recall his years in a human house, his capture, certainly not his life in the jungle. He remains stuck in the present, which, for an animal in captivity, means not thinking about why he’s here, how long he’s been here, if he’ll ever taste freedom.

A little bleak…but Ivan holds a trump card—the rare and singular gift of narration. Yes, the visitors stare at him. He stares back. We hear his voice alone. The set-up, the plot, the entire story—it arrives as one long riff on the experience of watching strange creatures through finger-smudged glass. Ivan may not speak much, but when he does we hear witness and accuser.

Now that her subject possessed a voice, Applegate needed to make him a hero. Even a child knows heroes don’t rescue themselves. Heroes free the weak. So she gave Ivan a cause—Ruby, a recently captured baby elephant whose innocence awakens Ivan’s sense of justice. He can’t bear to see Ruby imprisoned, and he risks everything to free her. Self-sacrifice elevates Ivan above mere zoo gorilla status, and he becomes that most venerated of creatures, a true silverback.

By allowing an ape to perform that most human and humanizing of acts—protecting the weak from the impossibly strong—Applegate tips the whole world of this book on its head. Suddenly no longer our “distant and distrustful cousin,” but our surrogate, Ivan represents at once our cold indifference and our clear-eyed conscience. In Ivan rises our capacity for compassion, redemption, greatness.

Applegate never settles for merely using or suggesting metaphors—she rattles their cages, then turns them loose. Furious, they break down the door. The 400-pound gorilla in the room turns out to be, of course, a 400-pound gorilla locked in a room. Not obvious enough for you? Don’t worry, we also find an elephant in the room.

A little heavy-handed perhaps, even for a children’s book? But consider—it all happened. Ivan the silverback gorilla, born in an African jungle, lived for 30 years in a shopping mall. And we paid to watch.

If Applegate’s book remains a testament to past wrongs, it also shines a light on current ills. A pivotal moment in the narrative hinges on something called a bullhook—imagine a long stick with a sharp metal hook at the end. Animal keepers use a bullhook to goad an elephant into performing, jabbing the device into soft flesh behind the ear or along a trunk. Maybe a tug behind the legs.

Google the word, bullhook. Videos and links from all over the world spring up. Animal rights groups want bullhooks banned. The city of Los Angeles recently did ban them. (Georgia, which did so well by Willie B, tried to ban them, but failed. Ringling Brothers apparently considers a bullhook ban to be a ban on the circus. A circus means money and entertainment…and no politician wants to stop either.)

In the book, the sight of this metal prod awakens a sleeping public to Ruby’s plight. Here Applegate seems to say it clearly: If even these people see the cruelty of bullhooks, why can’t we?

As for Ivan, the real one, he finally got out. In the 1990s, the mall went bankrupt, and its assets, including one western lowland gorilla, fell to the courts. Ivan’s fate became a controversial topic, argued and kicked around. In the end, people usually do the right thing. We may be slow, even reluctant, but eventually we get it right.

Ivan went to Zoo Atlanta.

There, for the first time in more than 30 years, he saw grass, the sun, trees. He hated rain. He wore a sombrero. He knew females (but none too well). He mated but never sired children.

Find out for yourself how the book ends, but know that the real-life Ivan died in 2012. As he lived out his days in Zoo Atlanta, his existence proved peaceful, if solitary. He grew closest to his human caregivers, a fact that speaks not only to an ape’s enormous capacity to forgive, but also to humanity’s capacity to heal as well as hurt.

In the book, Ivan—ever mankind’s beating heart—ponders our mercurial, enigmatic nature when he admits “I never know the why of humans.”

Don’t take it too hard, Ivan. Neither do we.

Kevin Hazzard, raised in the East but presently settling out West, is a freelance writer.