Orwell’s Animal Farm Is a Safe, Stale Videogame Adaptation of the Literary Classic

Seasons pass over the republic of animals. Since the chaotic revolution, ousting the human farmers from their cruel throne, the pattern of years rolls on. In spring, wildflowers bloom and the sheep play in the sunlight. In summer, the fields shimmer with gold and the animals graze freely. In fall, Boxer the horse brings in the harvest and the animals begin to move indoors. In winter, the barn decays and food depletes. In the fields, the cows and sheep work, building up a windmill or constructing a fence. Meanwhile, the pigs are in the farmhouse, reading and walking, becoming more human everyday. Even after endings, and dozens of permutations, it is a world in stasis.

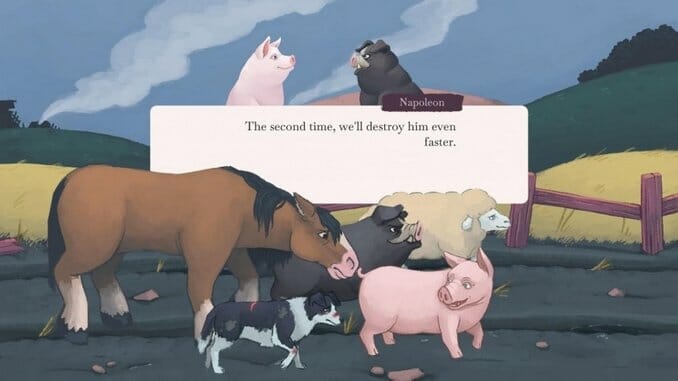

Orwell’s Animal Farm adapts the classic George Orwell novella into something that’s part visual novel and part strategy game. The player guides the characters of the novel through up to seven years of play. Short turns make up each season, interrupted by events from the novel or battles with the surrounding human population. Fundamentally, it’s a game about community management. The game encourages you to gather food and to lay up defenses. As with developer Neriel’s previous Reigns games, each of these choices come with a cost. Repairing the barn roof costs food stock. Promoting the Stalinesque Napoleon over the Trotsky-like Snowball will force the latter to lose power and vice versa. Understanding and pulling these different levers will lead to one of the game’s eight endings, as well as to smaller variants.

The player will find, though, that little can really change from their input. Whether it thrives, survives, or dies, horror lies in Animal Farm’s future. The explicit fail states are a reluctant return to the old order, death, abandonment, or starvation. However, if the farm survives several years, the endings are still grim and hopeless. The novella’s ending, where the pigs upend the rules of Animal Farm, essentially becoming humans themselves, remains. The other endings, for example, one where a council of pigs control the farm or the death of all the pigs leads to a directionless and hopeless community, are equally bleak.` At best, Animal Farm has traded the metaphorical dictatorship of a farmer for a literal pig oligarchy.

The game inherits this ideology from the book. It too, has a deep distrust of any kind of revolutionary action and a disbelief that anything could be better than the liberal status quo. However, it at least nominally works in the novel, because it is written in ink on the page. While there is, of course, subjectivity and interactivity from the reader, Animal Farm’s failure is an inevitable feature of the story. It’s a basic tragedy, like Hamlet or Oedipus. The animals fight against fate and lose. This is equally true of the game, but rather than being a slow slide into dread and horror, it gives you control. You can stockpile enough food for the winter, you can prevent the laws of Animal Farm from changing, you can keep both Snowball and Napoleon alive if you plan well. In a narrative sense, that work does nothing. Though much of the game is hunting through the interface for ways to make a difference, every ending is a bad end. When both the downfall and the continuation of Animal Farm are horrific, what can actually be done? The answer the game gives is a monochromatic silence.

Furthermore, the game fails to grapple with the source material’s bigotry. Making political allegory out of animals is a dangerous business because you will usually stumble into caricature and essentialism. When your working class analog is a docile, brainless herd of sheep, classism and racism follow. Like the novel, some animals get individuality, the pigs and horses most notably. However, most are monoliths of identity. Cows, goats, and sheep represent hard laborers, the pigs the intellectual class, the hens home workers. There is no poetry in it. It is, in fact, just cliché. There might be worth to it if the game had the daring to lampshade or complicate these metaphors. Such a game, though, would likely not get the approval of the Orwell estate. Because it is unable to meaningfully complicate its source material, it falls into a disdain for the “lower” classes, unwittingly replicating the logic of the story’s villains. Animal Farm makes some animals more equal than others.

To compellingly adopt something as entrenched in canon and classrooms as Animal Farm would require the daring to move outside of cliché and convention. It would have to engage with, and fight against, the text. It would have to make an argument with its play, reflecting its vision of dystopia in the decisions of the players. Instead, Orwell’s Animal Farm reheats a stale plea for the preservation of normalcy. In the middle of a massive economic, ecological, and humanitarian crisis, it feels hollow. The animals are doomed to die as they lived, unwell, uncared for, unhappy. Forever stuck in the programmed roles the game assigned them. When there is no way out, no real play, there is no message, no change. Animal Farm lives forever, dying and being born, always doomed to failure.

Orwell’s Animal Farm was developed by Nerial and published by The Dairymen. Our review is based on the PC version. It is also available for Mac, iOS, and Android.

Grace Benfell is a queer woman, critic, and aspiring fan fiction author. She writes on her blog Grace in the Machine and can be found @grace_machine on Twitter.