It’s impossible to escape the fact that Below is a Dark Souls-inspired game. It’s fascinating to see the different aspects of what was once a distinctive style in the Souls games becoming abstracted into something more like a genre—a set of tenets and general ideas that other games can draw from. While I never was quite able to get hooked on the Souls games, games like Below and last year’s Hollow Knight manage to capture some of the things that attracted me to that series, while still providing something different or approachable enough for me to grab on to.

In the case of Capy’s latest release, Below, it’s the game’s excellent use of procedurally generated design alongside bespoke level pieces that make it unique. On its face, the game is a roguelike, where after each death you are treated to a new set of procedurally generated rooms as you venture deeper and deeper into the game’s caverns. But the trick is always in the details, and Below takes full advantage of those details as it proceeds.

While each room is re-generated on death, the overall world map that each player has is unique to the player. While the interior of rooms is different, the paths to, from, and between them are largely the same. Coupled with that, the game has a number of preset occurrences on specific floors—for example, the 2nd floor always contains a path to the north shore of the island, from which you can find a shortcut to the 4th level, as well as a bonfire to save your progress.

The game is a masterpiece of slowly unfurling its systems to the player, in a sort of mechanical mirror of how it unveils each layer within the caverns. Like the Souls games, Below uses a checkpoint system based around bonfires. Sit down at one to rest, save your progress, and cook foods into stews (making them more beneficial to eat). If you venture too deep and die, you can use a bonfire on your next life to transport yourself back to your last-saved bonfire. From there, attempt to retrieve your corpse and its magical lantern, or fail and lose everything you were carrying. Use light motes to power that lantern, or spend them to save at a bonfire, in a weighty choice that feels similar to spending souls in Dark Souls. Each death starts you off with one bottle of water, which over time increases your stock of them (since, of course, you retrieve however many bottles were on your corpse if you can successfully recover it).

But what I’m finding most enthralling about Below isn’t just the game itself, but the conversations I can have about the game. Swapping secrets, shortcuts, hidden items and pathways, all of which are slightly different from person-to-person (due to the game’s procedural generation elements) but alike enough to carry a conversation—like the spear hidden in the cave north of the first bonfire.

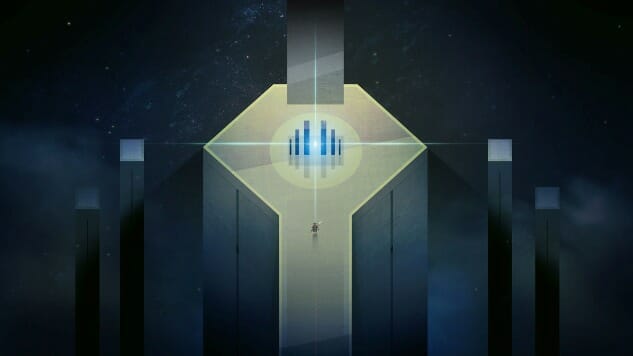

All of this comes together in the game’s aesthetic and audio landscape, which are perfectly tuned to make you feel not just that you are alone, but that you are deeply, truly, outmatched by the very world itself. The camera is so far zoomed out as to almost be comical in an action game, but it contributes to the feeling that this world is much larger than you—that you, as an explorer, are not native to this place, and it has existed far before you, and will persist long after you leave.

It is a profoundly lonely game, and yet it also has enough bespoke placement of items and objects that it never feels randomly slapped together, as some procedurally generated games do. Below accomplishes something that is rare in games—melding together procedurally-generated and individualized level design in a way that makes each player’s island feel both unique and communal, a shared nightmare with its edges constantly in flux.

Dante Douglas is a writer, poet and game developer. You can find him on Twitter at @videodante.