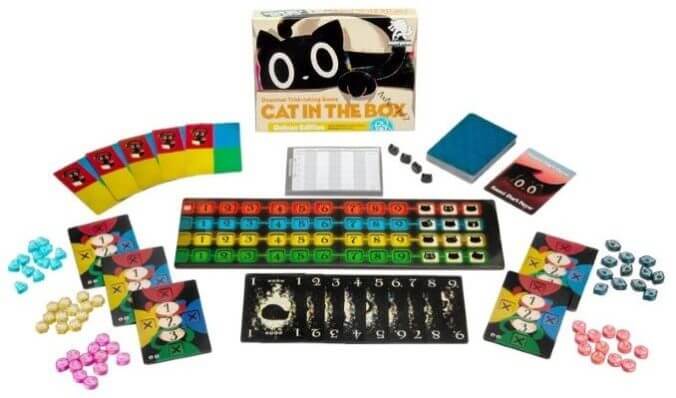

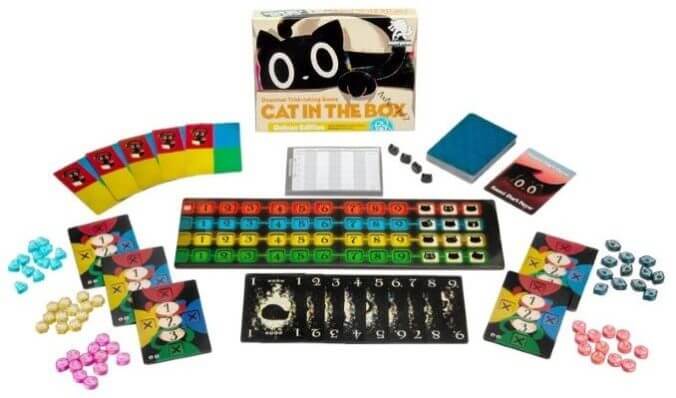

At Gen Con this year, I ran into a teenaged girl who was very excited to show me (or anyone in sight) that she had bought Cat in the Box: Deluxe Edition, because it was “cute” and had a cat on the cover. Maybe she really knew what a brilliant but challenging game was in the box and didn’t just buy it for the adorable box art. If so, I hope she forgives me for thinking, “oh, I really hope you know what you just bought.” I love this game, but Silly Cat Game it is not.

Cat in the Box, which is a new version of a game first published in Japan in 2020, is a trick-taking game that takes inspiration from the (in)famous thought experiment by physicist Erwin Schrödinger known as Schrödinger’s cat. In this hypothetical situation, there’s a cat in the box with a radioactive substance that has a 50% chance of having one of its atoms decay in a one-hour period. If that happens, a device within the box will shatter a glass with hydrocyanic acid (a.k.a., cyanide gas) in it, killing the cat. You can’t know if the cat is alive or dead until you open the box, but by doing so—observing the experiment—you also affect the experiment’s outcome, condensing all possible states, meaning the two where the cat is alive or the cat is dead, into one. The interpretations of this experiment vary depending on the school of quantum mechanics; one holds that the cat is both simultaneously alive and dead in the box, which, I contend, is not a thing.

Anyway, Cat in the Box turns this concept into a core part of game play: The cards don’t have suits (colors) until they’re played. They could be any of the four suits in the game until they’re observed by all players. When you play a card from your hand, you declare its suit. That specific suit-number combination must not have been played already in that round, and the player playing that card must still have that suit active—meaning that they haven’t previously declared themselves to be out of that suit. Otherwise, anything goes. The red suit is always the trump suit, and players must follow suit if they “can.” Of course, you can usually follow suit unless that entire color has been played in the current round, but you may choose not to do so for strategic reasons.

When you play a card, you declare its suit and place one of your tokens on the matching spot on the tracker board, which allows you to know which cards have been played already in the round. Highest card takes the trick and that player starts the next trick as well, which matters substantially because the player leading the trick has a big advantage—even more so when the entire red row is filled in on the tracker board.

The round ends in two ways: Once each player is down to one card in their hands, or when a player causes a paradox because they can’t make a legal play. The latter is more likely, as there are five cards of each number but just four suits, and players’ choices can be further limited by their decisions to say they’re devoid of specific suits. If you cause a paradox, you lose one point for every trick you won in that round.

The scoring for the rest of the players is a bit fiddly, and the only real part of the game I don’t love. Every player who didn’t cause a paradox gets one point per trick won. Before each round, every player predicts how many tricks they’ll win in the round—1, 2, or 3 if you’re playing with 4 or 5 players, or 1, 3, or 4 if you’re playing with fewer than 4. Players who won the number of tricks they predicted they’d win are also eligible for a bonus: they get one point for each token in the largest contiguous group of their tokens on the tracker board. This adds an area control aspect to the game, and can inform your choices of cards to play in tricks you know you’re going to lose or are deliberately trying to lose.

Cat in the Box plays 3 to 5 players, with variant rules for a 2-player game that eliminate the prediction aspect and have you fill in three spots on the tracker board, although I still don’t think a trick-taking game that isn’t designed for two players can ever work for two players. (Fox in the Forest is a trick-taking game for two players that actually works, but it’s a rarity.) I haven’t played Cat in the Box with 5 players, but it’s good with 3 and great with 4, with the deck scaling to fit the player count as well. I enjoy the intellectual puzzle that takes place in every round and on almost every trick, where you have to consider the immediate and long-term impacts of your choices of suits and even which numbers to play. You might try to hand an opponent a trick to push him over his predicted number, or play a specific card to block someone from building a larger group on the tracker board. Certain plays might be more advantageous now but more likely to cause a paradox later. Maybe it’s better to ditch the prediction entirely and just try to win as many tricks as you can, especially if you think your starting hand favors it. Every round brings its own puzzle and its own strategy, based on the cards in your hand. It’s kind of a blast to play, and the sort of game you can teach quite easily. It just might not be ideal for players who want a cozy cat game.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.