Come One, Come All for the Board Game Greatness of 3 Ring Circus

The idea in 3 Ring Circus is pretty simple: You’re running a small circus in the northeastern United States in the early 1900s, traveling through small towns, medium-sized cities, and large cities, putting on shows and hiring new performers or buying new animals so future shows can be more profitable. All the while, the great menace, Barnum & Bailey, makes its way around the map, and when they hit one of the big cities, there’s a scoring based on who has the most big-top circus tokens placed in that city’s region. When B&B completes one circuit of the map, the game ends and players count up their points, gaining from their objective cards, performer cards’ straight point values, and some performer cards that offer variable returns based on what else is on your board.

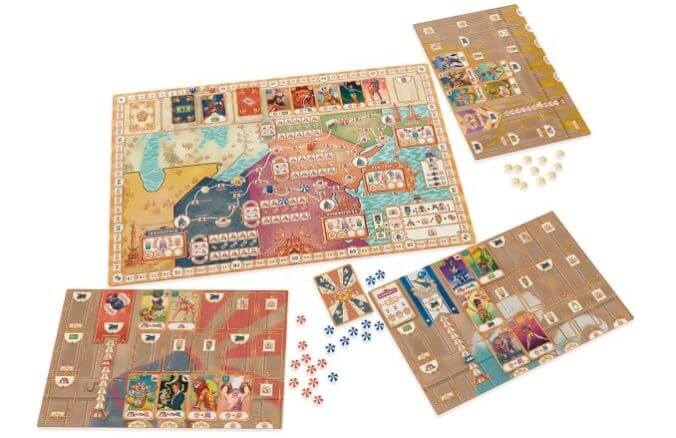

Turns are very simple in 3 Ring Circus—you either hire a performer from your hand or you move your caravan to put on a show in a new town or city. Every performer card has a value from one to 16 that indicates its cost. Money cards have values from one to five and can either be played as performers or used to pay for other cards. You have three open rows of five slots apiece on your board when the game begins, so when you wish to hire a performer, you first decide in which row you’ll place that performer card, and then you pay the value of that card minus the value of the highest-valued card already in that row—or zero, if the answer to that is negative. Playing that card might cover a symbol that tells you to draw another performer card or an end-game objective card, or might cover a symbol that reduces your income, movement, or circus’s entertainment value (pedestals). When you complete any of the first three columns, you get to play one of your objective cards. When you complete a row, you get from three to seven victory points. Enforcing balance across the board (pun intended) is a huge part of the game’s design, and part of what makes the game so good.

Moving to put on a show is a little more involved, because the shows at each type of stop work a little differently. Shows in small towns just generate money, while those in cities generate victory points and a little money. Shows in medium cities can also let you draw more performer cards rather than taking victory points. For small towns, you look at how many adjacent towns are still empty—that is, no one has performed there yet—and add one, then take that many money cards from the deck. You place one of your tents on a small town after performing there, blocking it for the remainder of the game to all other players. For medium cities, you look at your current pedestal count, add two if you have the type of performer that city wants (randomly assigned each game), and then place your token on the little scoring track in the highest empty space for which you have enough pedestals, taking either points or performer cards, and then taking one money card for every dollar symbol still showing on your board. For big cities, you must have a performer of the specific number shown on that city, also randomly assigned in each game, and can get more points if you have the right performer types in that same row. There’s also a three-point bonus for being the first player to put on a show in each big city. These are the biggest single point generators in the game, and you want to perform in as many big cities as you can, although it’s possible you’ll never get the right performer type for one or two of them. (You definitely want to snag those performer cards when they show up on the board.) You also take money for big city performances, one per dollar symbol on your board. You can only perform in any town or city once during the game, even if you’d be able to score more the second time through. They’ve seen your act, and they’ve had enough of it.