French Quarter is the latest roll-and-write game from some of the masters of the genre, Matt Riddle and Ben Pinchback, who also designed the acclaimed Fleet: the Dice Game, Three Sisters, and last year’s Motor City. They’re joined here by designer Adam Hill (Godspeed) for a new board game with some familiar elements that ramps up the difficulty rating without a steeper learning curve; once you get it, you’ll know how to play, you just may not know how to play well. (I don’t, yet.)

A roll-and-write game, for those new to the form, is just what it sounds like: You roll some dice, pick one, and then write at least one thing on your scoresheet(s). Yahtzee and Kismet are probably the best-known ones; I reviewed five favorites of mine, including Three Sisters, in a column last year for Wirecutter, and I could recommend another 10 or 20 if you have a moment. (Wait—where did you all go?) The beauty of these games is that they move extremely quickly. Either you all play simultaneously, or turns move fast because you just take one die and then write something.

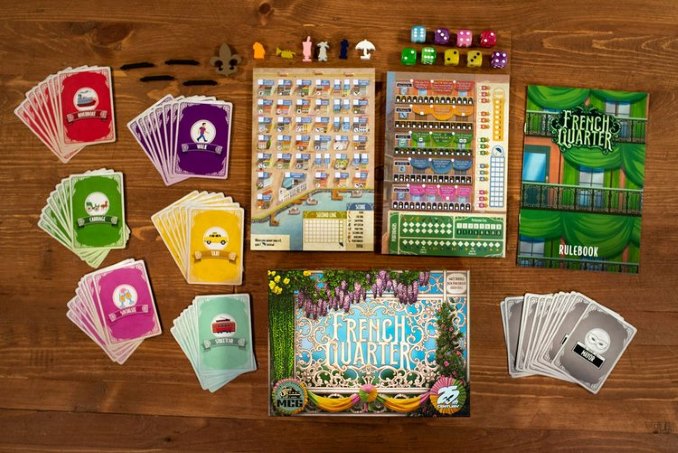

Like all of Motor City Gameworks’ roll-and-writes, French Quarter has two scoresheets per player, here representing a map of the iconic neighborhood of New Orleans and various tracks to mark what your tourist has done around town. As you mark off more squares, you’ll earn various bonuses that might let you mark off even more squares, often chaining bonuses to try to maximize the number of squares you’ll check before game-end.

French Quarter’s rule book is a little tight, but once you get the rhythm of the turns they move very quickly. Each round begins with the roll of the game’s dice, the number of which can vary a little by player count, after which they’re placed on the matching colored cards. Those cards represent methods of getting around the district—walking, riverboat, carriage, and “socializing,” among others. When it’s your turn, you select a die and then do three things with it: You take the action or actions shown on the card the die was on, you move your tourist meeple on your map sheet to another building and take the action(s) shown there, and then you “map” the building by writing the die’s value, if you haven’t mapped it already. (You can visit a building multiple times to take its actions, but can only map it once.)

Actions here mean marking off more squares on your sheets. Your second sheet has five activity tracks, each of which has a unique symbol and corresponds to one street on the map. You mark off squares left to right on those tracks, some of which will unlock immediate bonuses, ongoing powers, or game-end scoring. There is also a performer track, where you can get points for collecting up to two complete sets of eight performer icons; an umbrella track, the most common symbol in the game, where you get a free mark on any activity square for every three umbrellas you collect; and the second line track, which is a whole separate action that hits all players at the end of certain rounds. If any player chooses the socialize action, the second line will move one more block on everyone’s maps, and you check off one box in the second line’s track for every marked building that the second line passes on your map—not just on this turn, but from the entire game to that point.

Those marked buildings are the last part of your regular turn: you can take the die’s value to number the building on which your meeple is standing, as long as it’s within 1 of all adjacent buildings. Thus you can mark a 3, 4, or 5 next to a building with the number 4. This requires some advance planning so you don’t make it impossible to map a building, in which case you just get an umbrella but miss a bunch of points, from the second line to game-end scoring.

The biggest difference here from their previous three games, and I’d say from most roll-and-writes I’ve played, is that there is a huge internal conflict between the various options before you, because you have to pursue two disconnected goals to score well in French Quarter. You want to advance on specific activity tracks to gain their bonuses, and by doing so you’ll boost your game-end bonus for the streets associated with those tracks. Thus you also need to ensure your tourist visits more buildings on those streets where you have the highest bonuses, and that, my friend, is not easy to do when you’re three sheets to the wind on hurricanes and Sazeracs. The two often seem like they operate at cross purposes—the best track for advancement right now is not the best one for more points at the end of the game. And the activity track for socializing, which corresponds to Bourbon Street, actually penalizes you in-game as you advance, but promises the biggest end-game multiplier if you get all the way to the right.

French Quarter has a robust solo mode that hews extremely closely to the regular rules, making it easy to pick up and play once you know the base game. The box has a Mayor variant for multiplayer games that is required for the solo game; the Mayor gets a new card each turn, most of which will block off an entire street for that round, so you can’t visit any buildings on it and the second line can’t advance along it, and the Mayor also gets to take dice to reduce your choices. The Mayor doesn’t often choose the socialize die in the solo game, but can do so in multiplayer games, thus activating the second line. In the solo game, you’re just trying to max out your score, but it’s more than enough of an internal challenge to keep me playing it solitaire.

The game lasts eight rounds, with each of the transportation card types coming in an eight-card deck so you can’t forget how many rounds remain, after which everyone tallies up their scores. You get points for each of the five streets tied to the activity tracks, as long as you unlocked at least one scoring space for them, earning points for every mapped building on that street. You get one point per marked square in the second line, up to 60. You get points from your sets of performers, and can grab a few more bonus points if you move along that track far enough. You can earn bonuses from a few special buildings that you collect in sets or one building that gives you eight points if your tourist visits it twice. There are a few other smaller bonuses to collect during the game. It’s actually not that many ways to score, since five of them are identical and you may even get zero from one of them if you didn’t go far enough or chose not to take the end-game points.

I’m in the minority among fans of these designers in that I think Three Sisters is better than Fleet: The Dice Game; I found Fleet a little less internally cohesive, and Three Sisters incorporates its theme about as well as any roll-and-write I’ve ever played. I’d put French Quarter in the middle; it’s more fun and more visually appealing than Fleet, but not quite at the Three Sisters level, and definitely better than last year’s Motor City for aesthetics and game play. I love the way the game confronts you with that conflict between gaining something now and ensuring you get points at game-end. And it turns out that it’s appropriately hard: you can play this game and get some points, but if you want to do well, you’re going to have to do some hard thinking. Those are the best kinds of games in my view, regardless of their style.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.