The Great Tekhenu: Obelisk of the Sun Is a Heavy Board Game That’s Not Too Heavy

Italian game designer Daniele Tascini has made a name for himself with heavy worker-placement games since his acclaimed 2013 game Tzolk’in: The Mayan Calendar (co-designed with Simone Luciani), which featured a novel and very fun set of interlocking plastic gears of different sizes on the board that changed what actions and resources were available on each turn. His follow-up, 2018’s Teotihuacan, had an extremely busy board and offered even more choices, earning more plaudits from fans of complex, crunchy games.

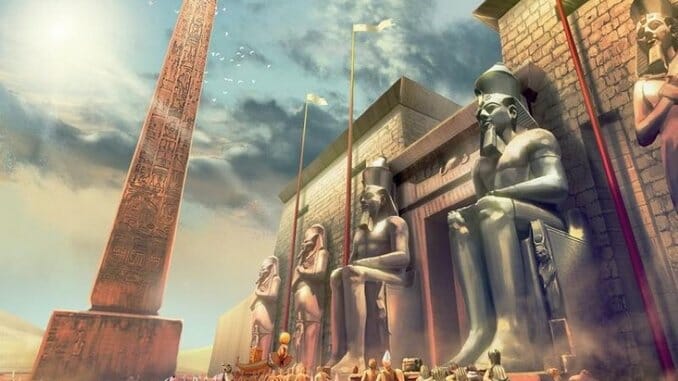

His newest title, the dice-drafting game Tekhenu: Obelisk of the Sun, is still a heavier game, but it’s easier to grasp than his earlier games of this ilk (or the other new game I’ll discuss below), with a slew of options on each turn but relatively simple rules for choosing your actions. The real complexity here comes from deciding on your strategy with a board that offers many different areas for scoring, many of which are interconnected, and the supply of cards that let you do more things and change the ways in which you score. It was good enough to make my ranking of the top games of 2020.

The heart of the game is the obelisk of the game’s full title, a large plastic tower that stands on the board on top of a rotating disc that shows three different shades of beige or brown, representing sun, shade, and night. The six sectors of the circle around the disc will contain dice rolled at the start of each season and some rolled after each round, but the dice will move between the three bands in each sector—pure, tainted, and forbidden. The die colors go to different bands depending on whether it’s sunny, shaded, or dark in that sector, and in most cases you can’t take a forbidden die.

Once you take a die, you’ll either take the action for the god associated with that sector, or you’ll use the die’s value to take the matching resource. The game has four resources, each of which has a unique action that requires it, but if the die’s value is higher than your production capacity for that resource, you get the extra cubes but they count as excess and go with any tainted dice at the end of certain rounds. Otherwise, you can use the god’s actions to build buildings at the temple or in the quarries, build pillars in the temple (which score in concert with buildings, and vice versa), gain cards, grow your population and increase its happiness, or erect statues to the gods. There’s some interaction between these different areas of the board, although the cards are very powerful and your strategy may depend on the card you get at the start the game and those you pick up while playing.

The game has 16 rounds in which each player will take one die, and at the end of each even-numbered round, there’s a judgment phase where the values of the pure dice they took are added and measured against the values of the tainted dice plus those excess resources from any dice used for that action. If your Tainted values are higher, you can lose victory points, and the closer your total is zero (balance), the higher you’ll go in the turn order for the next two rounds.

There are two scorings, one after eight rounds and one at game-end, where you’ll get points in six different areas—the temple, the quarries, statues, your people’s happiness, any production tracks you maxed out, and bonuses if you’ve built at least seven buildings—plus whatever bonuses you get from cards.

Tekhenu gives you a lot of choices, and it’s unlikely that you’ll ever have nothing good to do except maybe in the final round, but there appear to be many different paths to victory. The cards are the most powerful, but you’ll need to combine that with two other god actions to rack up enough points for a win. There’s also an easy-to-use solitaire mode that lets you fine-tune the difficulty level to your liking. Tekhenu is about as heavy a game as I like, and I’m more critical of games at this level because I think a lot of games of this weight are complex for complexity’s sake, but this one really seems to work, and there are so many choices that you’ll want to play it again.

Tawantinsuyu: The Incan Empire

Board & Dice published Tekhenu and Teotihuacan, as well as a similar new game, Tawantinsuyu: The Incan Empire, another heavy, complex game, that I think is totally overdesigned and borderline unplayable. The rules for placing your workers on the ziggurat, and what resources/actions they can take once placed, are too arcane, and you have five different types of workers, each of which has a unique ability. Once again, you’re trying to collect four different resources and spend them across the board, building stairs on the central temple, constructing buildings and temples, raising an army, and more. There’s even a feature where you collect tapestry cards to try to create matching patterns for more points, which feels like its own mini-game entirely within yet disconnected from the overall game. It’s mechanic upon mechanic and the rules/fun ratio was way too high for me.

Keith Law is the author of The Inside Game and Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.