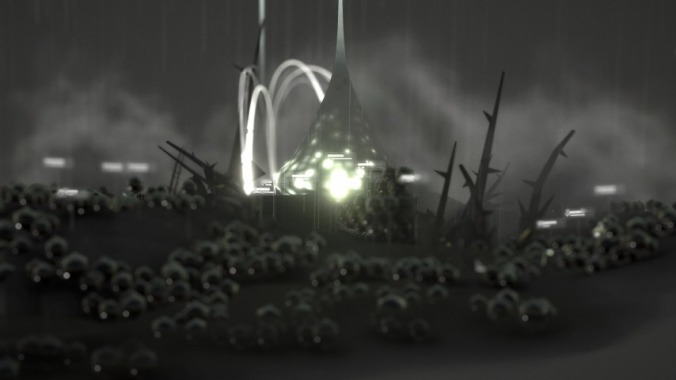

Bobby Technology’s Chaotic Era, as I’ve written before, is an aesthetically and thematically dark sci-fi RTS game set hundreds of years in the future, where humanity is forced to the stars after destroying our home world and must struggle to survive, spreading through and exhausting our solar system. The game’s aesthetics and action capture the fear of the unknown, the futility of conquest, and how the desperation of violence can transform people for the worst—all staples of the genre, though not every game seems to be so purposeful in messaging through mechanics. Chaotic Era is a challenging game that can sometimes feel unfair because of the way procedural generation reshapes the map for each scenario of conquest-borne conflict, bringing demise to a Human (or Alien) base before it’s been properly set up. Although this computated griefing can be frustrating (how many times in a row can one reasonably be expected to keep playing after dying within 130 seconds?), it does lend an air of grit and authenticity to the game. The hellishness helps drive home the points that space is an uncaring vacuum, and that colonization begets violent resistance, themes already imbued in the gameplay.

Chaotic Era starts with tutorial-style missions that acclimate players to life as a project manager-military strategist for the human refugee faction and conveys the desperation of survival. You learn quickly how to build a base, how to fill the codex by discovering the surrounding area, how to use the tech tree, how to improve your units’ abilities with the codex’s own leveling system, and how to find and eliminate enemies. It isn’t a game that spells out the irony of invading somewhere to make a home and calling the local fauna aggressive (and are they local or have they torn across time and space too?); it’s just there for you to see and experience. After playing through those start-up missions for the Human settlers, you eventually unlock similar missions for their Alien counterparts, the bane of Human existence in this world. The Alien physiology is strange, though the mindset as expressed to the player is simple and understandable enough. It boils down to “Why are the humans here? What are they doing? How do we get rid of them?” It is a mutual understanding of infestation and of limited space and resources. There is no room for diplomacy here; peace was never an option.

The missions in the two starting chapters of the campaign (five Human missions and five for Aliens) have very different win conditions because of the different circumstances of their existence. The humans are colonizing; what is alien to that faction is not alien to the system—you can just run out the clock; in the grand scheme they will always outlive the humans in this space. As long as a few survive, there will always be more; this is, apparently, the Aliens’ home.

The story is fleshed out through the tone of the mission objectives—humanity is trying to find a new home, has to put down mutiny, has to exterminate a native population. The humans take the aliens as aggressive and the campaign seems geared, like many games, to train you for multiplayer. The aliens don’t get substantially less exposition than the Humans, but we all know what Humans are and we know that Alien is a broader category.

The Alien faction is simultaneously charming and dreadful, the latter more because of the unknowability communicated when you run the Human faction, their sudden appearance, and their brutal effectiveness. They operate out of “hives” and “membranes” rather than “basecamps” and “barracks.” They are arguably more efficient; they “summon” “Scabs” (think a beetle-slug hybrid, a land-crawling crustacean) as their main worker and battle unit, but the eggs which the hives spawn work both as building blocks for new structures (corresponding to the supplies that Humans produce) and as fighters on their own (corresponding to the Humans’ “Sleds”). One of their strongest offensive units is the Hunter, a single circular eye shape with a cloud skirt billowing behind it; they are summoned out of portals in the ground. When you play as the Aliens, the Humans feel like cruel, unstoppable, metallic invaders into your home system.

There is a level of automation and alienation in the way human business is conducted here. Workers and fighters are the same unit type, moving in sync, aimed at a specific job or opponent. The weapons conduct electric currents, a terrifying proposition if you imagine yourself as an alien traveling too close to a Scanner tower or a Vuture turret—automated death targeting you for extermination. The comms chatter is terse and spartan. There are no pleasure-chasing adventurers, no witty soldiers of fortune, no overenthusiastic patriots, but still a hint of the warnings of Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers in the unknowable nature of the enemy, the single-mindedness of your protagonists. The automation relates an acknowledgment that the real hard work to survival past a certain point of technological advancement isn’t just efficient architecture, and maybe just killing whatever is already there isn’t the best way to go about creating a society or a civilization. Maybe it’s all we have left because merciless tools of destruction are what we have turned ourselves into.

Many RTS games rest on assumptions about human nature and our drives to exploit, exhaust, expand, and exterminate (the classic 4X formula leaves “exhaust” implied, but even story-based roleplaying games maintain this philosophy despite differing mechanics). From time to time, this assumption is communicated through the mediation of morality; there tend to be good guys (House Atreides, the GDI, the Allies, the U.N., etc.) and bad guys (House Harkonnen, the Brotherhood of Nod, the U.S.S.R., the GLA, etc.) who operate with parallel functions. One tends to appear more American or “Western,” the other some composite, analogy, or representation of U.S. adversaries: Nazis, Soviets, vaguely-defined and poorly-understood Islamist terrorism. Here, it’s aliens, which creates more obvious contrast, and makes the similarities bleaker.

Aliens are not new to the RTS game. One of the genre’s biggest franchises, Starcraft, counts among its first factions the Zerg and, therefore, its audience coined the term “Zerg rush” for efficient—and arguably unsporting—deployment of mobs of its base unit. The CPU-controlled side in Chaotic Era will mob you with Spores, but it will also mob you with Sleds. Chaotic Era’s aesthetic does call back to an earlier era of RTS games and to an older era of science fiction, but its thoughts on technology, at least, are more advanced than some of those predecessors. Perhaps its thoughts on how people move through the world cannot help but to be.

Kevin Fox Jr is a writer and critic who loves art, culture, sports, cooking, and the study of history. He writes, mostly about movies, games, TV, and books at his blog PCVulpes, and you can find him @polycarbonfox on X, or @phantomcobra on BlueSky.