Dishonored 2 Transforms the Liminal Space of Elevators into Dynamic Devices

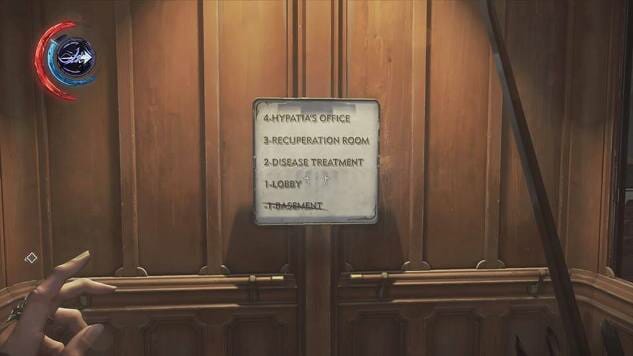

During a recent session playing Arkane’s Dishonored 2 I found myself stuffed into the attic crawl space of the Addermire Institute with my dead lover’s heart in my hand. Aside from the creepy sentimental value, I was using it to spy out the collectible runes and bone charm power-ups scattered around the building. There was one remaining rune that, for the life of me, I could not find. Glancing to my left at the open elevator shaft bordering the attic, I suddenly noticed the thick cables mooring the elevator to the roof. Videogame convention made me consider them indestructible, but the cables gave way easily to a quick sword strike, sending the elevator hurtling down and through the ground floor and opening up an entirely new area that had previously been inaccessible. It was at this point I realized that Dishonored 2’s elevators were special.

Elevators in games as well as real life are inherently liminal spaces. They exist well outside of the bounds of architectural and social convention. Forced inside these cramped spaces, we struggle at awkward, stilted conversation as we wait interminably for our floors to arrive. Elevators are spaces that are extraneous to where we want to be and what we want to be doing.

Games tend to uphold this understanding of elevators by employing them by and large as punctuation between levels. Portal uses elevators as a literal demarcation between one test chamber and the next. Mass Effect infamously features over-long elevator rides complete with muzak and strained conversations. That these long, confined pauses double as loading points for the next area only further serves to mark their isolation from the rest of the game.

Dishonored 2 does something different with its elevators. With few exceptions, the elevators in the game, in accordance with its Victorian aesthetic, are antique-looking cage elevators. By their very design, they are open and exposed to the level. Closing the doors does not mean sealing yourself in, as much as briefly containing your movement within a loud and conspicuous box. When you arrive at a floor, the doors open with a cacophonous ding and can often alert nearby guards. Luckily the maintenance workers of Serkonos are all equally absent-minded and you can beat a quick escape through the roof hatch and over the heads of the oblivious sentries. Better still to use the loudness of the elevator as a distraction by sending it to a floor you aren’t on or even crashing down the shaft.

This newfound functionality of elevators can be understood as a subversion of their liminality. In Being John Malkovich, the rote function of the elevator is similarly subverted. The elevator is transformed into a dramatic device, allowing John Cusack’s character access to the 7 ½ floor where much of the action of the plot takes place. Even Mass Effect 3 challenges expectations set by earlier elevators by turning the assumed boring elevator ride to the council chambers into a tense setting for a firefight. Dishonored 2, by designing elevators that affect and are, in turn, affected by the surrounding environment, similarly subverts the expectation of videogame elevators as dull and extraneous spaces that have no immediate effect on play.

Once you realize its potential as yet another physical object that can be manipulated, the elevator in Dishonored 2 becomes a powerful tool. Though the wide slats in its walls might serve equally well to expose you, the elevator can also be used as a moving recon platform, allowing you to get a quick count of the guards on a particular floor before you arrive at the landing, and turning into a bastion what easily could have been a coffin.

Elevators are also great for setting up traps. If you’ve got an arc mine or a spring razor in your inventory, the elevator serves much the same function as the rats that scamper through the back alleys of Serkonos. While a rat with a spring razor attached to its back is an unpredictable ally, you can drop a few spring razors onto an elevator, send it up to a floor brimming with guards and let its noisy announcement act as a natural lure—allowing the mines to do their work.

Dishonored 2 is foremost a game about exploration and traversal, where you constantly have to find your way into places you don’t necessarily belong. Elevators play their part, allowing easy access to the shaft and to small maintenance doors above the main ones that allow either for a quick escape or a great launching point for a sneak attack upon the curious who came running to see who’s actually taken the elevator (it would seem most of the guards prefer the cardio offered by the staircases).

The elevator in the Clockwork Mansion level offers even more routes and accesses that lead you into narrow crawl spaces, exposing the hinged and levered nature of the previously solid-seeming rooms of the mansion. When it comes down to it, everything in the mansion is effectively an elevator, adding greater thematic impact to your frequent trips under the floors in spite of hollow admonitions from the mansion’s proprietor, Kirin Jindosh.

The transgressive nature of this type of exploration is the setup for the elevator scene in Being John Malkovich. When Octavia Spencer’s bored office worker jams a crowbar between the elevator doors and directs John Cusack to a narrow space between the normal floors, this ritual feels unnatural and mysterious. Its humor is wonderfully subversive, using the banality of an elevator in an office building as the portal to a world where nothing quite makes sense, but where everyone crouches down and rolls with it.

Being John Malkovich couldn’t have employed this dramatic conceit without the reasonable fear, reinforced by Hollywood action movies, of leaving the safety of the elevator and venturing out into the shaft. There are no shortage of movies featuring characters crushed and maimed by elevators. These spaces are not for people, after all. Floors, stairs, even roofs are for walking around on. But elevators are special. They’re conveyances that dangle you over the void as you traverse from one habitable space to another.

To embrace the void is to embrace the ethos of Dishonored. The sneak, the assassin, doesn’t travel the same steps as the rest of us. Hers is a path through drainage pipes and atop slippery rooftops. She must take advantage of every potential route even if it means exploring places previously the domain of dust, cobwebs, and desiccated corpses clutching diaries and bone charms.

Transforming elevators from extra-architectural waiting areas into dynamic devices to be used alongside the rest of your tactical arsenal is a testament to Dishonored 2’s flexibility as a game. It follows that in a game dedicated to making the player feel transgressive, the elevator should be given higher purpose that the rote banality it is normally relegated to. As a result, the player gets to feel like Octavia Spencer, jamming the doors open to reveal a strange world, brimming with possibility.

Yussef Cole is a writer and visual artist from the Bronx, NY. His specialty is graphic design for television but he also deeply enjoys thinking and writing about games.