How Games like Dordogne Use Mixed Media to Explore Family Dynamics in a Nuanced Way

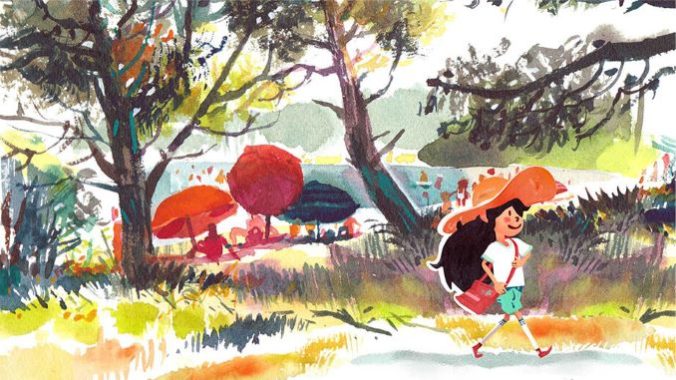

A couple chapters into Dordogne, Un Je Ne Sais Quoi’s title known for its gorgeous watercolor-styled graphics, Mimi remembers when she first found and used her grandmother Nora’s scrapbook. Mimi’s bratty and restless 12-year old self (who you spend half of the game playing) did so while spending her summer vacation with Nora in 1980s rural France. She gets severely scolded (almost disproportionately so) for using it to sketch a picture of her estranged parents in pencil crayon on a page. But soon after Nora apologizes for the incident. She explains in a contrite manner to Mimi that she was possessive of the scrapbook because it was meant to capture memories of Nora’s late husband Édouard and her son Fabrice, Mimi’s controlling ex-military father, but that it never got used. Nora then allows the 12-year-old to keep the scrapbook and let it be her record of the memories she makes during this summer visit. It becomes their way to connect with and learn from each other’s different experiences.

But the scrapbook is more than just a narrative device. Other than a series of somewhat finicky point-and-click actions to perform, the player’s central mechanic for Dordogne is scrapbooking. You collect stickers for it by exploring environments, paste photos you’ve taken in it or even generate cringey poetry from one-word thoughts that occur to Mimi throughout the memories she’s making and reliving. This scrapbook/scavenger hunt mentality of preciousness and play is extended to the present, as a 32-year-old Mimi reconnects to her grandmother and regains her lost memories through discovering a playful set of posthumous notes Nora has left for her around her old property in Dordogne. You also make tape recordings of sounds you associate with specific memories, listen to tape recordings of your late grandfather and read old family letters. My favorite tape recording so far is that of Édouard capturing the sound of an old motor car as he predicts to an exasperated Nora that future generations won’t know what old cars sounded like because their cars will be silent.

The sequence where you first encounter and start using Dordogne‘s scrapbook set some gears spinning in my head, especially with regards to intergenerational divides and how evolving technologies and nostalgia for analog modes of expression can signify these divides in games. This sequence also, in my opinion, points towards how the deconstruction of the traditional family structure is hotly debated. Often technology is blamed for the atomization of the nuclear family. After all, the more screens we have the less attention we pay to each other, right? But I think this is only half-true.

Technology can keep us estranged from one another at times but it also helps us stay connected more so than in the past, when there were less immediate means of communication across distances. And when it comes to videogames, which have powerful potential for expression, such technology also helps us portray family dynamics in a nuanced way. Dordogne is only one game that displays the medium’s ability to showcase how complex interconnections between different generations and their attendant forms of self-expression and art-making can be. Our media is intertwined with our nostalgia and often nostalgia points towards what different generations believe or hold dear.

We’re all quite aware at this point in game development history that games are media uniquely equipped to explore various systems of interaction. Games, as Game Developer blogger Arne Neumann notes, are an inherently mimetic medium that began by digitizing pre-existing “concepts and game formats” such as tennis or tabletop roleplaying games. As games became more like the ones we’re familiar with today, they also began to mimic other forms of art and storytelling, especially those that center audiovisual and performance design. With the above in mind, it’s easy to see how over the years games have gotten very good at telling stories about families and their individual histories and dynamics. I haven’t seen much discussion, however, of how games utilize mixed media to signify family dynamics across different generations.

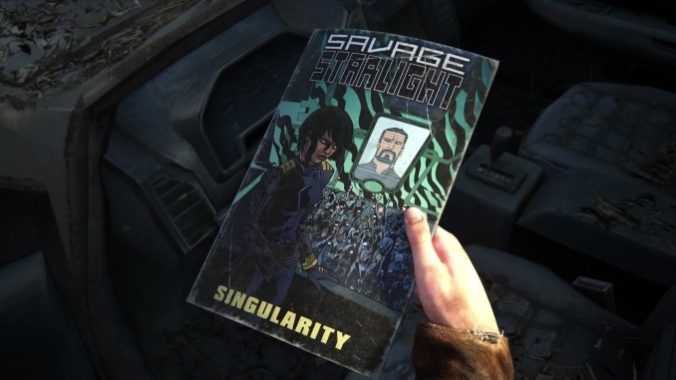

I previously wrote that stories about found families and intimacy like The Last of Us are stronger than most because they model the intergenerational connections of Joel and Ellie not just via the overarching narrative, but by having the player collect multimedia like comics, letters and dictation recordings. This referencing of tactile media from previous generations is deliberate and threaded through to the sequel as well, where Joel (and by extension the player) plays guitar to express his love for his adopted daughter and we find Ellie chronicling her coming-of-age, grappling with grief and rationalizing her plans for revenge in a journal filled with her idiosyncratic writing and evocative drawings.