Resonance (PC)

Sometime in the 1990s, the big guns in the games industry became obsessed with physics. It makes sense: you’ve got “3D” visuals, which are “realistic”, and so you want them to behave in “realistic” ways. Plus you’ve got years of mathematics and scientific research to provide you with the equations to model “realistically”. And computers are used in all that stuff already, so they’re a perfect fit for games!

So, physics: procedurally generated interactions between objects in space. What was interacting became less important than how they interacted (though maybe all those 1990s modders who tried to plug their favorite franchises into Quake are an argument against that). This posed a problem for the point-and-click adventure game.

Pointing and clicking doesn’t lend itself to physics (see the late LucasArts entries in the genre, the 3D Escape from Monkey Island and Grim Fandango, neither of which is played with a mouse alone), and so large studios’ development of point-and-clicks stopped, killed by physics.

Which is why I kind of like that Resonance’s story is about, among other things, physics (it includes a rather topical puzzle set inside a supercollider!). A researcher has developed a new technology that, like all good post-atomic age scientific discoveries, is simultaneously a potential source of limitless energy and a potential weapon of limitless destruction.

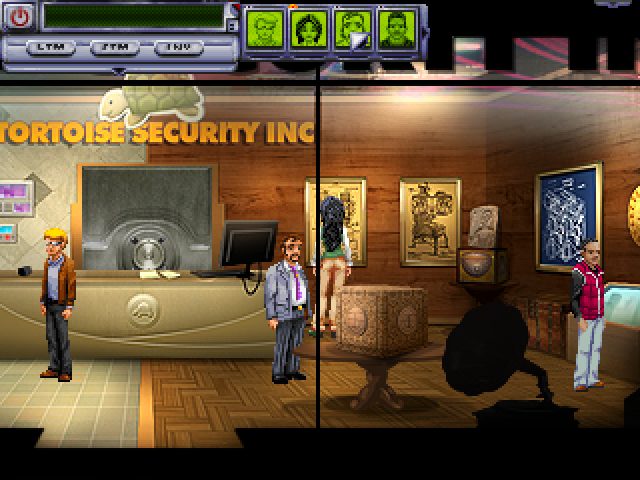

A city-wide blackout and an explosion at his lab brings together the game’s four playable characters, each a twist on a hard-boiled noir type. There’s the cop with an attitude, the journalist (“blogger”), the affable-but-apparently-clueless guy (who happens to work in the lab), and the femme fatale, whose dreams reveal surprising connections to the deceased. Things get very complicated.

When the game introduces you to these four characters, each is limited to a single location. You work within each area to solve its particular puzzle and lead the characters more or less to where they will meet up. But it’s smart: each of these individual bits introduces you to information that you will need to find later. It’s a kind of foreshadowing that reduces the urge to run to a walkthrough at the first sign of frustration.

Games based on how you play provide a challenge for a single person (and if you can’t defeat that challenge, you can always hand control over to your little brother, who will make that jump with ease), but there’s something potentially hive-mindy about adventure games.

If you’ve got Internet access a walkthrough for solving the puzzles is within easy reach.

And since in point-and-clicks, what you manipulate matters more than how you manipulate it, out goes that particular challenge.

Rose-colored memories of puzzles based on wordplay (combine “Ipecac Flower” with “Maple Syrup” to create “Syrup of Ipecac” so the giant boa constrictor that’s swallowed your character will vomit you out) drown out the often obtuse, brute-force “combine every item with every other item” (the Inventory Spam Maneuver, or ISM) strategy that many games required.

Most point-and-clicks were two separate systems: an inventory system and a conversation system. Generally, a conversation would involve you choosing a line of dialogue from among several listed. Then you’d read (or listen to) the other character’s response. Repeat until you’ve exhausted every option and you’ve got The Dialogue Tree. Sometimes you could ask about an item in your inventory, but for things in the environment (signs, gaping holes, dead bodies), you were out of luck, unless the conversation system added another dialogue option after you looked at said environmental object.