Common People: An Interview with Roadwarden Developer Aureus

2022 has indisputably been the year of the narrative-heavy game. We’ve had NORCO, Immortality, Citizen Sleeper, and, if that’s not your style, the cumulative hundreds of hours of JRPG cutscenes that have been released this year. For narrative game freaks like me, this is excellent news. The varied complexity, length, and depth of these releases means we’re all spoiled for choice. And as of this fall there’s yet another text-based adventure to add to the list, one that matches the season with a chill and a feeling of adventure.

That game is Roadwarden, a simple but deceptively detailed text-based RPG from Moral Anxiety studios that has been a smash hit in RPG communities. It’s a pixel-art fantasy that takes place over the slow slide into autumn and turns into an investigation of the twisting, overgrown roads of a faraway peninsula. It’s also a massive undertaking, consisting of thousands of lines and dialogue that changes based on your character’s health, emotions, and personal goals. In short, it’s a mini epic, one that is made all the more impressive for being produced (for the most part) by one person.

I spoke with developer Aureus about the inspirations behind Roadwarden, the game’s approach to unsettling nature, and what’s next for the studio.

Paste Magazine: What were your main inspirations for Roadwarden? Were there novels or other games that especially inspired you?

Aureus: I wear my inspirations on my sleeve; the problem is keeping track of all of them. I used to read one fantasy novel after another, but I lost my passion for this type of literature once I started studying the Western canon at university and reading became my duty. Since then, my relationship with reading has been tense, often uncomfortable, and I usually read novels that are inspired by politics and history, or are touched by magic realism.

There were games I fell in love with as a kid, Baldur’s Gate, Fallout, and Planescape: Torment, and as an adult I’ve been fascinated by modern classics that encouraged me to take another look at game design, player expression, and reactivity in games in general. Pyre and Kentucky Route Zero are among my favorites. The fantasy world I built, which is heavily inspired by Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay’s setting, is a remnant of tabletop role-playing trends from Poland, while parts of the game’s interface and systems are based on very old text-adventure games and printed gamebooks.

Roadwarden is a web of all sorts of texts, and it can never be fully untangled.

Paste: How did the game develop from its initial form into what it looks like now?

A: I wrote the raw design document in 2018, and started to work on the first prototype in January 2019, less than two months after a previous, catastrophic game release. The finished game is surprisingly similar to the early prototypes, though it grew in scope, complexity, and quality. I had to learn how to draw, reinvent the game’s style of narration, and add new game systems complementing the stories as they were unfolding.

I see Roadwarden as “my” game, but it received a lot of help. I can’t imagine it without Nick Roder’s music, without Lisa Olsen’s text editing (and, bluntly speaking, the English lessons she gave me), without the kind people who helped me on the forum dedicated to the game’s engine, or the players who gave the demos a shot and shared their feedback with me. Even if I’m responsible for 99% of the time and effort put into the game, filling up the remaining 1% would take me another few years.

Paste: In Roadwarden, nature is threatening but also part of the world. Can you talk more about why you made that human/nature tension so central to the game?

A: First of all, it took me a while to realize how the movies of Hayao Miyazaki, foremost Princess Mononoke and Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, affected me more than a decade ago, and how vividly their shadows are present in Roadwarden’s themes and world. These attempts to ponder the relationship between nature and civilization, merging beauty with violence and the search for one’s purpose with world’s ambivalence, have nourished me ever since I was a teen and was taking my first steps into fantasy writing.

It’s likely that I have a blind spot, but it feels to me like most fantasy worlds, especially in videogames, see nature as a resource, or a passive source of beauty that’s fading away because of “dark powers” or greed. The woods, lakes, and coasts are the realms of humans, with a few dark swamps and ancient forests, all filled with monsters. Delving into my world of fiction, I tried to take away assumptions some of us take as a given, design a realm that belongs to the wilderness. Here, humans are an intrusive, undesired force.

Such words are more common in post-apocalyptic fiction, with its deserted landscapes and distant hills covered with ashes of the once-great civilization. George R. Stewart’s 1949 novel Earth Abides was a great source of inspiration for me in this regard, especially as I finished reading it in early 2020, just before the pandemic revealed its many tales of empty streets and of animals returning to their dwellings. Stewart portrayed the reclaimed lands as green, vivid, cruel, and in no need of a master. Therefore, in “my” wilderness I wanted to avoid putting humans in the center. In the game, we’re not the harbingers of doom, nor the gardeners selected by divine beings, even though the quote that inspired Stewart’s book comes from Ecclesiastes: “generations come and go, but the earth abides.”

Paste: Those associations make a lot of sense; Roadwarden has a lot of elements that seem to come from CRPGs, novels, and other genres. There’s even sections that reminded me of an adventure game. Yet text is the player’s central way of interacting with the world. How did you decide to format the game as a text-based RPG?

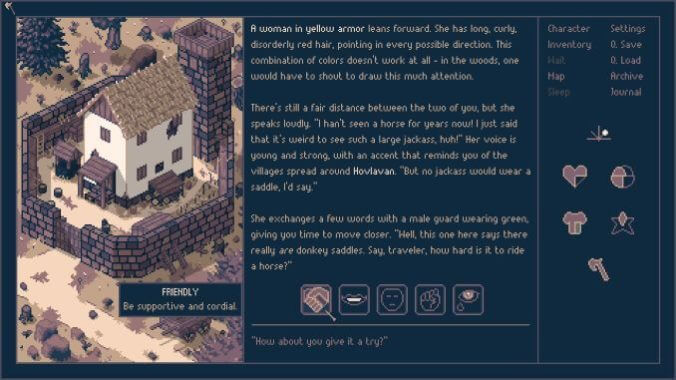

A: Let’s start with what most people would rightly accuse the game of: a massive block of text is the cheapest type of content a game can have. I wrote many scenes that use just the sentences put next to a static picture. Playing large-scale video RPGs one expects unique animations, music adapting to the flow of the scenes, voice actors, lighting, moving faces… My work resembles that of the developers from the ‘70s or ‘80s, though unlike them, I’m not a programming genius, and I do have some points of reference I can rely on. I don’t need to invent the wheel.

I must say, however, that using narration opens many opportunities as well, and can’t be cast aside as a mere replacement. Many of the scenes and interactions portrayed in Roadwarden are there because I could handle them, adding words and branching stories without the baggage of adding the work of another 10 to 40 employees. Some of these events are loud and busy, others are intimate and silent. It takes a wide range of skills to capture all that through sounds, visuals, and acting—but a single writer can handle them.

At the same time, using narration can improve the pacing, maybe counterintuitively. Players mention the game is free of grind, and that its entirety feels like a dynamic experience. That’s exactly what I wanted to accomplish. I hoped to avoid padding, and there are many sections in the game where the text replaces long, boring discussions, or exposition, or travels, or scenes of violence, or of boring labor. Some of the NPCs and areas would have never been added to the game if it wasn’t for the narration trimming the fat.

Paste: What you say is exactly true—there’s a LOT of text. Especially text that changes every time you leave a town, for example, when you get descriptions of what the women washing clothes and the priests are doing. What was your writing process like, and why did you feel it was so important to focus on these little descriptions?

A: When I experience fantasy stories, I feel more connected with farmers and workers than I am with the kings and nobility, to their luxuries and sense of superiority. I hope Roadwarden will be many different things for many people. But to me, personally, this creative process is what I needed to explore my tendency to be alone, as an uncompromising (and obnoxious) individual, but also the desire to be a part of a tight community, where people depend on each other not just out of their will, but also out of necessity and proximity. Therefore, instead of portraying rows of warriors in shining armors, I wanted to offer the players a look into the lives of the “common” folk, who try to survive and who struggle, build friendships, share rituals and convictions. This might be seen as intersecting with cottage-core aesthetics, which can be toxic and deceitful, but as long as one’s open to see the true side of the fantasies they offer—the poverty, the sickness, the fertile ground for bigotry—there’s value in seeking a simpler life, one focused more on the people that surround us. It sure beats those weird masculinity-obsessed Internet subcultures of recent years.

It’s also possible I’m overthinking the fact that Fiddler on the Roof is my favorite movie and I just love tales about small villages, even if they have a grim end.

Paste: What do you hope is next for you? What’s your dream project?

A: My hopes pull me in two directions. I’d love to see a game smaller in scope, but more personal, focused on a single settlement and how it tries to find its identity over the years, maybe with a single protagonist across a generation or two. The twist would be the immersive, Roadwarden-like focus on personal relationships, with many decisions altering the group’s future in a bittersweet manner. Then again, I have a more palpable design for an opposite game, focused on a group of adventurers exploring a vast area over the course of three seasons. I’d like to play with the ways the members of the company would change with time and how their relationships would either get stronger, or fall apart completely.

In both cases, I know I can’t handle such games on my own. I’d need a producer, a small crew, or at least a real programmer. So it may be that I’ll spend the next few years looking for a job at a large corporation as a quest designer or a writer, and fade into obscurity.

Emily Price is a former intern at Paste and a columnist at Unwinnable Magazine. She is also a PhD Candidate in literature at the CUNY Graduate Center. She can be found on Twitter @the_emilyap.