Spec Ops: The Line (Multi-Platform)

A significant portion of Spec Ops: The Line is spent cowering behind a wall. From a third person perspective, we watch Captain Martin Walker follow the orders we input through our controller: wait for the perfect opportunity and then execute the kill. Then do it again. And again.

In the typically strained relationship between player and videogame protagonist, there is a constant tension. The player knows better. He knows that Walker is headed down a road of death and destruction and misery. He knows that the faction isn’t following orders; that things will get messy, because that’s the type of story this is supposed to be: a horrible one. We wait with baited breath for things to go wrong.

But Walker’s not stupid. He understands the problems with refusing direct orders to remain outside of Dubai, to radio for backup to carry out the actual rescue mission. He understands that they are in danger if they continue into the city and engage these apparent enemies. More importantly, he understands the risk that comes with “going rogue” just as the battalion they are attempting to rescue has. He understands that he could be wrong.

While there is indeed a significant overlap between the motivations and expectations of the player and protagonist, that starts to change as the firefights become more heated and as the protagonist grows more impulsive. Spec Ops: The Line turns the heat up on Walker ever so gradually, resulting in a story arc that illuminates the vast gulf between the mindset of a civilian player and the soldier at war.

The game opens on a standard blockbuster-style set piece, complete with a turret sequence and an explosive finish that concludes with a hard cut to black. The clichés continue with a flashback to the beginning of the story and the root cause of these events. We watch Walker choose between grey areas, and we sympathize with his intense desire to be an honorable hero. And yet, as the choices become more difficult, the two men in his battalion begin to doubt him.

But they still follow orders without question, at least when standard-issue killing is the plan. One of the primary mechanics of Spec Ops: The Line involves aiming at enemies and pressing the right-bumper, which causes Walker to call out an order to his troops to take them out. This is the safest way to fight—shooting the occasional bad guy myself every now and again, but for the most part barking out kill orders to my squad. When one of them takes too much damage, Walker can simply instruct the other to heal him. Walker calls the shots, trying to keep his hands as clean as possible.

Still, Walker occasionally has to get dirty. At the player’s control, Walker kills legions of soldiers. The shooting controls are gratifying and simple. Death is easily offered up to the seemingly crazed and mislead groups that insist on keeping Walker and friends from completing their self-assigned mission.

Mechanically, the game finds ways to set itself apart from standard war games: third-person perspective, cover-mechanics, squad commands and the occasional ethical choice give the game a decidedly distinct feel. Beyond that, they serve a purpose that only becomes evident later in the game: they provide the player with a significant sense of distance from the avatar.

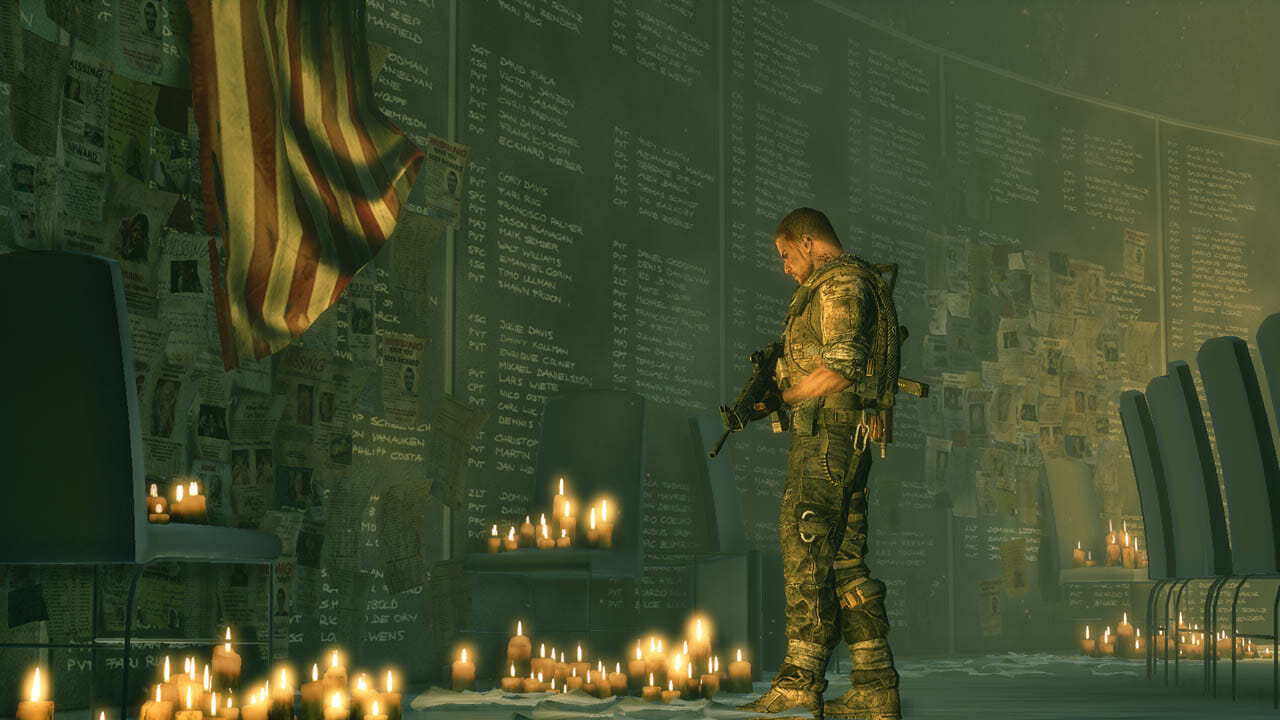

Because we’re not playing in first person, we don’t automatically equate every single action with our own. Because we’re staring at the faces of our character and not down the barrel of a gun, we think about characters and their reactions rather than our own. We see Walker’s war-torn body as the battle drags on. We see a concerned look on his face as he barks out a command. The focal point of the game becomes the soldier, not the explosions or the targets. And we see the physical action of hiding behind a wall, the posture of a man who is, at least to some degree, afraid of being shot. And then, we make him press on.

The game’s few ethical choices are an offering to the player that causes us to feel empowered in the midst of a series of dead ends and screw-ups. The more frustrated we become with Walker’s situation and the atrocities we are witnessing along the way, the more we crave the ability to change this world—to make a mark on it ourselves. We are convinced that Walker needs our guiding hand, and so we gleefully make the choice to save civilians, or to execute the man who most deserves it. These are still difficult choices, but at least they are choices we can own.