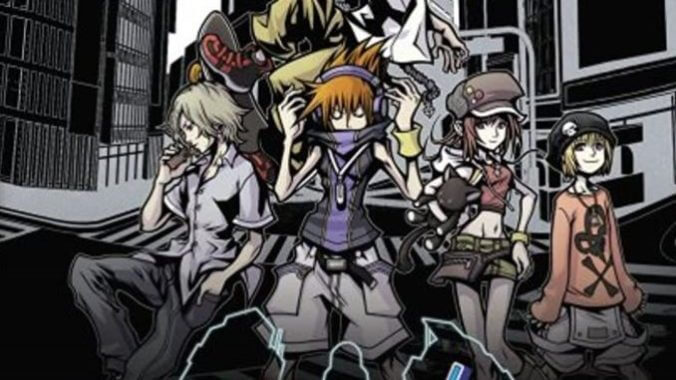

Action RPG The World Ends With You is a tremendous and underrated game, one whose strengths are also probably part of the reason that it wasn’t a more significant commercial success despite being one of the Nintendo DS’ greatest offerings. Of course, it had help in this with its relative lack of promotion: Square Enix as a merged corporate entity has been around for 20 years as of this April, and they’ve spent much of those two decades failing to market much of anything that wasn’t attached to Final Fantasy. There are exceptions—NieR:Automata, which continues to be pumped up by Square for good reason, springs to mind—but we are talking about the publisher that sold off the rights to Tomb Raider because they weren’t quite sure what to do with one of the most successful franchises in history, which is also the publisher who sees a lot of success with non-Final Fantasy projects when they let someone like Nintendo publish (and market) them outside of Japan, instead.

While it’s easy to fault Square Enix for not doing a better job of promoting The World Ends With You, which celebrated its 15th anniversary in North America this April, part of the issue is also that it’s a game that needs to be experienced in some way for how cool it is to fully click. It’s not just the in-game obsession with fashion, or the killer and varied soundtrack, or the version of Shibuya that’s on display. There’s nothing quite like TWEWY out there, to the point that even its remaster and sequel aren’t quite like the DS original. And it’s because they couldn’t be: The World Ends With You was designed with the strengths and specific features of the DS in mind, and those can’t be replicated elsewhere since we live in a world where the Wii U failed and the 3DS retired. Not that Square bothered to create a sequel to The World Ends With You for either of those systems when they had the chance, but now we’re just getting off track.

The reason for all the “you can’t do this anywhere else” about a game that actually was ported elsewhere eventually is because The World Ends With You tied its gameplay to its narrative in a way you can’t quite untangle without changing the fundamental nature of both. The World Ends With You: Final Remix on the Switch is still great, because it’s a version of The World Ends With You, and even a faulty version of it is vital and enjoyable. It’s only a “better” game in the sense that the sound and graphics have been reworked, however: it plays worse, because it lacks the two screens of the DS, and those two screens played a huge role in crafting a narrative that was directly linked to The World Ends With You’s gameplay.

You play as Neku Sakuraba, a 15-year-old who lives his life annoyed at the existence of other people. He believes he doesn’t need anyone to get by, that everyone else is less intelligent than he is, or their morals more in question than his, and walks through life with his headphones on trying to drown out the lives and concerns of everyone else around him. He’s deeply lonely, and quick to lash out, putting his own problems front-and-center in a way that makes him unable to see with ease when reaching out or listening could also benefit him. For significant chunks of The World Ends With You, Neku veers between deeply unlikable and someone you feel deep empathy for: you can see, before he can, that he is someone who needs to let someone else in, or else he’s going to go down a path that rots his soul.

The World Ends With You features Neku trapped in a week-long life-or-death contest called the Reaper’s Game. Fail in the game, and face erasure; succeed, and earn your freedom. There’s no way to win this particular variation of the game without partnering up with someone else, however, and in a move that surprises no one who already spent five minutes with the kid, Neku remains very resistant to this even when it becomes clear he can’t even move beyond the invisible “walls” the Reapers put in his way without a partner around. He will be erased because of his stubbornness unless he learns to work with others. He’s nearly tricked into killing his first partner, too, because he’s promised what he thinks is freedom—you can’t overstate how much Neku just wants to be left alone, and it makes him nearly intolerable.

With time, though, he learns to rely on other people. Part of that happens in dialogue and through vignettes, sure, but the battle system is where both you and Neku learn the value of teamwork in the Reaper’s Game. You have to control both Neku and his partner at the same time, with different control inputs, on different screens. In order to master the gameplay of The World Ends With You, Neku must be fully in sync with his partner, meaning, you must be fully in sync with yourself.

As Jordon Oloman wrote for NME back in 2020, right before The World Ends With You received a sequel, “The best part about all of this is that the game ties its elegiac co-operative combat mechanics to the central thesis of its narrative. Despite what the title may suggest, the point of The World Ends With You is that it doesn’t. The game’s withdrawn protagonist can wear his headphones in the scramble and push away anyone who gets close to him, but the truth is that we need to give parts of ourselves to others in order to understand our existence and thrive… Neku isn’t able to endure the Reaper’s Game—or any combat engagement, for that matter—without the help of his friends on the opposite screen.”

The way you do this is by using the stylus to control Neku’s actions with touching and swiping, and those of whomever his partner is—there are quite a few of them, surprise surprise, the Reapers aren’t exactly truthful about what’s going on or how any of this works, necessitating you and Neku to play the seven-day game far more than one time through—will be controlled with either the D-pad if you’re right-handed, or the DS’ cross buttons if you’re a southpaw like myself. Neku is equipped with pins that you level up through use and successful battling, and each has a specific way of being utilized: an early fire pin requires you press and hold on an enemy or area with the stylus, while another is a physical attack that sees Neku dash across the screen and slash at an enemy you slide the stylus across. Yet another has you swipe up with the stylus to attack with ice from below, another has you swipe at objects in the direction you want to send them flying… there are a whole bunch of motions to make with the stylus, and you need to be aware of which pins are active, which are cooling down for use later, and where Neku is relative to his foes in order to avoid damage while dealing plenty yourself.

And at the same time, you need to be paying attention to the top screen, where Neku’s partner is. Up there is a rhythm-style game that allows for powerful attack combos if you nail the sequences: directions will be shown, and you press the corresponding direction for the attack you want to use. A successful string will cause additional damage and pass a green “puck” of energy to Neku, allowing for him to attack with more power; the puck is then passed back up top when Neku pulls off a successful string of attacks, and so on until the battle ends. The better you perform in battle—which is to say, the more synced up you are, and the more successful you are at making sure both Neku and his partner are firing on all cylinders—the more experience points you’ll get afterward, which further levels up your pins and makes you tougher to defeat. The best pins are available as rewards on tougher difficulties, and without extra levels and a true sense of what you need to do to not just survive in battles but to wipe the floor with your foes, you won’t be getting them—you can change the difficulty at any time to increase both the challenge and the rewards, and you’ll want to, but first you have to, like Neku, master the concepts of teamwork.

It can be frantic, there’s no denying that. The enemies on the top screen are the same enemies as below, with Neku and his partner essentially fighting them on different planes of existence. If they die on one screen, though, they also die on the other, so there will be times where Neku’s pins are all cooling down and you have to focus on avoiding damage with an enemy you can’t repel, while at the same time his partner is trying to pummel them to death with rhythm. It takes some getting used to, but is highly rewarding, and part of the reason people who have played The World Ends With You are so high on a game that Square has kind of struggled to explain the appeal of for 15 years now.

In the Final Remix remaster of TWEWY, both Neku and his partner are on one screen. You must equip your various pins in a way that’ll result in a summoning of his current partner, so they can contribute to the attacks. You can still get in a rhythm here in a way that makes for what appears to be teamwork, but it’s nothing like the superior original in this sense, because the narrative and gameplay no longer intertwined like they were: it’s the same game, but also not at all the same, no longer designed to reveal the lie of the game’s title like on the DS. This is Neku’s game and journey, but it’s his actions that allow for his partners to participate, rather than a true partnership split down the middle, with two characters working in tandem, and Neku understandably growing as a person from this experience and becoming one you could actually stand to be around.

NEO: The World Ends With You, the 2021 sequel to TWEWY, was far more successful in devising a battle system to replace the dual-screen setup of the original. Rather than simple partnerships, you now have a full-on party, and your protagonist isn’t the only one equipped with pins any longer. Fitting all the pieces together and taking full advantage of everyone in battle, fully understanding what they’re capable of and who you can trust to handle specific situations and who can come to the rescue at which moments: you’ve got a lot to think about here, and it fits into the game’s overarching narratives about teamwork and evening the odds in a way that the previous modern-day outing simply couldn’t, living in the shadow of a game whose successes it couldn’t fully replicate.

Which is a long way of saying that The World Ends With You as a series can live on even in a post-DS world, because, horsepower aside, Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft (Windows) all do generally the same things in terms of their hardware, in the sense they’re all plugged into a TV or a monitor and utilize a gamepad. But the specific marriage of narrative and gameplay that powered The World Ends With You can’t be replicated without technology that can achieve the same goal in the same way. Maybe Square could have put in the time to figure out how to run The World Ends With You: Final Remix in a vertical orientation with the Switch undocked, each Joy-Con detached and controlling one of the two characters on separate “screens” stacked on top of each other. Hey, the Arcade Archives series and various shoot ‘em ups include a TATE mode to replicate the arcade experience—maybe non-arcade games could take a cue from those. Maybe Nintendo’s next console will allow for this sort of thing to be more easily encouraged, so that some of the variety of the DS and Wii U era can exist once again—a hybrid console capable of either TV or portable play has been excellent, but there was something wondrous about how the DS could be held either in its standard form or vertically like a book (sometimes even within the same game!), providing for a wide array of control schemes and inputs that, when combined with the two screens, allowed for the creation of ambitious games like The World Ends With You in the first place.

Final Remix was a reminder that we’ve lost something with the death of the dual-screen format and a return to the homogeneity of console design. That’s not to say that any of today’s games lack ambition or push the limits of design or what have you, but it does mean that something so inextricably tied to its platform like The World Ends With You is harder to make in the first place, since there isn’t a box to think outside of. Which in turn means that reviving The World Ends With You isn’t quite as special now on today’s platforms as it was when it first came out. If you can, if you still have a DS or 3DS, find yourself a copy of TWEWY so it can be played the way it was meant to be played. You’ll be glad you did, as I am every time I’ve fired up this classic of the Square Enix era.

Marc Normandin covers retro videogames at Retro XP, which you can read for free but support through his Patreon, and can be found on Twitter at @Marc_Normandin.