There’s a rhythm to fighting the Noise, a pulse that goes beyond the click of a stylus or the press of a button. Every battle in The World Ends With You requires that you spread your attention across multiple bodies, multiple means of engagement, and most practically, across the Nintendo DS’s two screens. The current versions of the game, on Switch and mobile, remove this element. Everything you need to see is on one axis of engagement, a screen unsplit. The most daring things about The World Ends With You are absent from its remakes. That’s a damn shame.

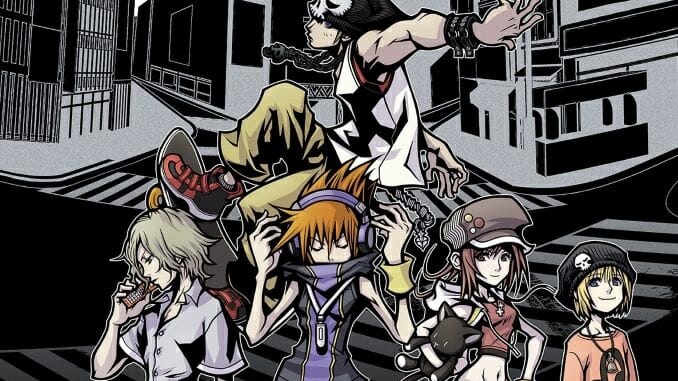

The World Ends With You (from now on TWEWY) is an action RPG about fashion and friendship. Angsty anime boy Neku wakes up in Shibuya. His memory lost, he quickly discovers that he is both dead and has been drafted into a game with his to be resurrected life on the line. In order to escape the game, he must team with a variety of partners and learn to trust other people. If this sounds a little bit rote, that’s because it is. Neku is angsty in a way that echoes countless shonen protagonists. His arc from aloof to passionate is familiar. This is not exactly a problem though. Neku’s companions: Shiki, Joshua, and Beat, all get grounded and emotive storylines. Shiki in particular gets a melancholy depiction of jealosy and friendship abound with queer resonances.

TWEWY’s primary narrative problem is not its tropes, but its obfuscation. Neku is gruff and distant at first, but, despite a couple gestures, the game doesn’t explain why until close to the end. It is simply difficult to get invested in Neku’s journey to belief in friendship when we know nothing of his past or motivations. Additionally, much of Shiki’s interactions with Neku are trying to get him to care. The primary source of inter-character conflict feels lifeless. Luckily, TWEWY’s strengths are not in its cinematic or literary modes. The game shines in its most action RPG moments.

TWEWY’s play re-enforces the game’s thematic concerns and gives a sometimes sterile narrative expression and weight. To put it simply, TWEWY is about the joyful difficulties of cooperating with others. Nowhere is that clearer than in the game’s battles. In each fight, the player controls two characters, one per screen. Neku is on the bottom screen, controlled with the stylus. One of Neku’s partners is on the top screen, controlled with the d-pad. Neku is the more immediately customizable, with the ability to equip pins that activate attacks when the player taps, dashes, or presses the stylus. Each of Neku’s partners work differently, but all require the player to tap the d-pad to map out patterns and combos. The player must balance controlling both of these characters simultaneously. It’s an affordance that only could have come with designing for the DS’s unique architecture.

At first, this is decidedly awkward. Enemies flip between screens. The game allows you to dodge with both characters, however dodge mechanics vary between Neku’s partners and all require you to read enemies’ visual clues. That can be difficult when you have to pay attention to two screens at once. Therein though is its power. It emphasizes the game’s themes of cooperation. Anyone who has worked on a group project knows that getting people to work together is hard. It often requires that your attention be on multiple things at once or that you briefly attend to someone else’s needs before your own. In motion, the game is about overcoming one’s stubborn and useless independence. That lends its tropes power that they would not otherwise have.

There are plenty of things that do transfer from the DS version to its mobile and Nintendo Switch remakes. I adore the fuzzy pixel art of the original, but the hard inked, Saturday morning cartoon lines of “Final Remix” have a charm all their own. The blocky, low resolution sound of the music has its own beauty, but I would also love to hear the music as it was recorded. Most importantly though, is the game’s setting of Shibuya.

It would, of course, be deeply silly for me to talk about the accuracy of the depiction of Shibuya, as somebody who does not live in Japan. What’s more important is that it takes the district seriously as a place. Shopkeepers remember you from day to day. Trends ebb and flow; you’re incentivized to follow them because wearing the right brand gives you an attack bonus. There are multiple battle songs and multiple wandering around town songs. More are added with each in-game day. This variety gives the feeling of exploring a city, scrolling into a mall and hearing top 40 hits, before dipping into a record store to jam out to a local group. The prescription of a bonus to trends is obviously a kind of conformity. However, trends can vary from block to block and you can brute force your favorite brands to the top. It is, at least, a multiplicity of conformities. (It’s also worth noting that every brand is fictional). It’s on some level crass and commercial, sure, but also reflective of the weird existentialism of being a teen in capitalism. All this must be, at least mostly, intact in the re-releases.

All this is to say that if you don’t have a DS, but have a Switch (and you are willing to pay the Switch tax to obtain it) Final Remix is probably worth a shot. It is absurd to claim that such versions are “not the real game.” Besides, streamlining TWEWY’s unwieldy combat surely comes with its own virtues. Still, it’s hard not to feel the loss. The game’s primary narrative charm is in its unwieldy, cooperative combat. Though the tropes encourage a resignation to familiar archetypes, fighting keeps you on your toes. Even late into the game, new mechanics are introduced quickly. You are learning more about other people around you day by day, step by step.

That experience has been left behind, left only to emulation, piracy, or the shelling out probably a little too much money for a cartridge on eBay. If you are lucky, like me, you still have a copy around. Otherwise, Square Enix isn’t going to help you find one. The World Ends With You proves a lot of things. It proves how far an expressive setting can push narrative forward. It proves the untapped potential of action RPGs, the variety of settings and ideas they could inhabit. Most of all, though, it proves that what we want to preserve from the past we have to take. Re-releases will often not retain the most daring parts of history.

Grace Benfell is a queer woman, critic, and aspiring fan fiction author. She writes on her blog Grace in the Machine and can be found @grace_machine on Twitter.