Walking Among the Enemy: Wolfenstein II and Passing

Contains spoilers for mid-to-endgame content in Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus.

“I recognize your face. Very Aryan face it is, too.”

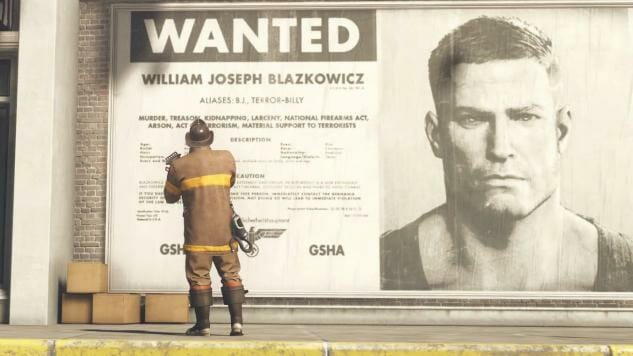

Sitting at the diner counter in Roswell, New Mexico, William Blazkowicz is asked by a Nazi commander for his identification papers, but not before he compliments Billy on his facial structure. After all, the Nazi sees Blazkowicz and sees a white man: Broad-shouldered, blue-eyed, blonde. He’s not that different than the commander himself, another white man in a country that loves whiteness and maleness.

The scene recalls a similar one in 2014’s Wolfenstein: The New Order. BJ, stopped by Nazi Lieutenant Irene Engel on a train to Berlin, praises the man’s “very nice Aryan features.” As the train rumbles through the hills, Frau Engel tests Blazkowicz with a series of Rorschach-style association tests. Here are two cards, she says, point to the one that fulfills the category given: excitement, fear, arousal.

In The New Order, Engel’s test acts as an example. By the end of it, she reveals the cards meant nothing. They never did, there’s no way to test “Aryan-ness” by mental association. There’s not really a way to test it at all. The lesson here isn’t that there is a “right way” to pass in Nazi society, but that Nazi society sees what it wants to see.

Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, like The New Order, begins with a tragedy. Here it is a much more personal one, with a child Billy living through the horrors of an abusive father.

This scene also establishes something the Wolfenstein games have danced around for ages: BJ Blazkowicz is, on his mothers’ side, Jewish. His father, a hard-bitten Texas businessman, is white, and unafraid to trumpet that fact.

These initial scenes are brutal. The physical and emotional abuse of both BJ and his mother, Zofia Blazkowicz, is on full display. The man conducts himself as a tyrant, and with the same racist, sexist and oppressive language that would define the future Nazi rule of America. He stands, dark-clothed and just above your sight-line as he ties your hands to a shotgun. “It’s on us to straighten out the queer. It’s on you,” he roars.

In Rip Blazkowicz’s mind, BJ is white. Rip, too, sees what he would like to see. Blurs out the rest.

I grew up in a town that was 85% white. A tiny 1.5% defined themselves as African American in 2010, and the demographics weren’t that different twenty years ago. My mother is black, her father was black as well. Growing up here meant realizing that most people would see what they wanted to see from me. I have relatively pale skin. I keep my hair short. In many cases people didn’t even suspect I wasn’t white unless I mentioned it.

This is racial passing. It’s a complicated term with a complicated history, especially in the United States. Racial laws during and post-Slavery led to a “one-drop rules” in many states, marking citizens with even “one drop” of African blood as black. The history of American racial segregation is filled with this obsession with purity and wholeness, with whiteness being the purest, most whole state.

Passing allows for an individual to access places they would usually be barred from. It is a privilege, no doubt about it, but like all privileges it is based, fundamentally, on an unjust system. I grew up knowing that divulging my heritage was a risk around mixed company. You could never really know who would snap when learning you were a “hidden” black person.

To assume that BJ’s whiteness defines him as a character is wrong, but to assume it plays no role is also wrong. BJ passes. His mother was an immigrant, and a Jewish woman—two evils in the eyes of the Nazis, and William inherited one. He also, importantly, inherited his father’s build and white skin. These, too, become weapons in BJ’s arsenal.

When we talk about whiteness as a system of racial supremacy, we must understand that in order to participate in it and benefit from it, the constant identification of whiteness must be preserved. For BJ to be publicly Jewish would mark him, even though the Nazis stridently affirm their belief that Jewishness is somehow “detectable.”

BJ is their own walking paradox, a Jewish man passing among the Nazis and enacting a bloody spree of revenge wherever he goes. Because he can pass.

And, also, therein lies the biggest criticism one can make: BJ exists because he can exist. Were BJ, as a character, designed as a black woman, or a darker-skinned man, or anything other than the “acceptable” white-passing figure that he is, we probably wouldn’t have seen Wolfenstein rise to the prominence that it has.

My joy at BJ’s characterization is, like anything that involves passing, bittersweet. Every party, social gathering, classroom I go to where a racist joke pierces the air, I know that I am only allowed here because I have the privilege of not wearing blackness as openly as others. Every time I do not have the courage or the strength to challenge racism, I know that it is due to privilege that I even have the choice to. I have the privilege to hide in my own skin.

In some way, this is a part of William Joseph Blazkowicz. We see it in Roswell, as he walks unperturbed down the streets of Nazi guards. We see it in the train, in The New Order, as he is unafraid of Engel’s racial interrogation. We see it when Black Revolutionary leader Grace points out that BJ will never face persecution like she will. It is the constant understanding that you are wearing the skin of your own oppressor, a cloak you are never going to be able to take off.

There is a scene, at the end of BJ’s return to his childhood home, where he finds his own father—his abuser, his mother’s abuser, the most abject face of the racial and anti-Semitic hatred that he grew up with—waiting for him in his old room. He scolds BJ for having the gall to return, of how ungrateful BJ is. He tells his son how much better things are with the Nazis in charge, how much better it is with “the Jews, the coloreds and the queers” all rounded up. Once again, Rip still sees Blazkowicz as of his same blood, a white man under it all. He sees what he wants to see.

And BJ kills him. It is brutal and it is quick. And we know it isn’t over. It is not a perfect solution. It never will be, to use white-passing bodies to triumph over white supremacy. There will always be more to do.

But for a moment, we can celebrate—because there is William Joseph Blazkowicz, the race-traitor, the passing Jewish man, the walking paradox, our hero. An avatar of the suppressed rage that is so familiar to myself and other white-passing persons, using the complicated politics of passing as a cudgel against the mechanics of racial supremacy. It is a deep and nourishing revenge.

Dante Douglas is a writer, poet and game developer. You can find him on Twitter at @videodante.