A hand-drawn adaptation of an under-the-radar manga about a bald high-schooler’s oddball band sounds like it probably doesn’t have many mainstream peers based on its description. But writer/director Kenji Iwaisawa’s weird, hilarious and deadpan On-Gaku: Our Sound is a musical, magical trip with a quintessential slacker vibe. A narrative filled with DIY punk artistry and misfits bumming around, On-Gaku: Our Sound is an indie sensation that’s got at least one major stylistic contemporary: Richard Linklater, the master of the mood whose breakout feature is literally titled Slacker.

On-Gaku follows the meandering days of Kenji (Shintarô Sakamoto), Ota (Tomoya Maeno) and Asakura (Tateto Serizawa) as they while away the time after class. They’ve got a reputation among the local high schools for kicking ass…but we never see them do much besides standing around the same room, playing the same old-school videogame and walking to the same café. An often silent, drawn-out, semi-stoner humor permeates their lives, more attributable to the monosyllabic grunting of teen boys than to bong rips. They’re weird, but in the immediately recognizable way of Slacker’s Austinites.

Where the colorful Texans offer their conspiracies and discontent to anyone who’ll listen around campus, On-Gaku’s similarly magnetic suburban trio possess a younger aimlessness that hasn’t quite yet found the things they want to obsess over. They’re judged, like the “burnouts” and fringe-dwellers of Linklater’s early work, but in a way unique to Japanese adolescence. They’ve somehow gotten a reputation (somehow as legendary, fantastical martial artists) and, as the film shows, that’s more than enough to define them—despite their innocuous actions.

They shift between the constant motion of Dazed and Confused’s wanderers and the sweaty stillness of SubUrbia’s loiterers. They venture out deeper into their sunny, sleepy town when asked to fight a rival school…until they give up because (oops) none of them actually knew where the hell they were going in the first place. They’re literally directionless—though they’re so open to options that they strike out with the barest of information. Their school’s folk band, all long-haired finger-picking hippies, are the ones who’ve already picked their evangelical eccentricity.

The relationship between the two seemingly disparate groups reflects that momentary dissonance when you remember Linklater helmed School of Rock, where a person’s singular passion is so overwhelming and total as to become educational by default. It all slips back into harmony when On-Gaku’s boys, like the classmates under Jack Black’s tutelage, embrace the folk dweebs with open and appreciative arms—even giving the wannabe-atniks new musical modes to appreciate with their guileless, instinctive rock. It’s that music that pushes On-Gaku beyond its Mike Judge-esque humor and simple style, finding the heightened plane of existence that Linklater reserves for the rotoscoping of his more ambitiously heady efforts.

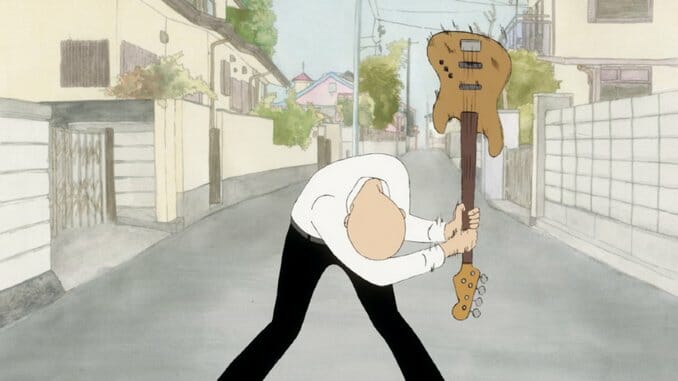

As soon as Kenji and crew smack their instruments—two bass guitars and a sparse pair of drums—everything changes. Until that moment, the anime’s been purposefully sketchy and low-key: Kenji’s eggy head and scribble of a ‘stache create the kind of silly, unassuming look that helped define One-Punch Man’s dry humor. It also helps Iwaisawa’s indie production keep costs down. “We didn’t have professional creators working on this project. And I also didn’t have skills, so this was the only route we could take to create this film,” he self-depreciatingly told Anime News Network. As soon as music enters the equation, though, the film evolves. “The camera goes from stagnant to kinetic as it moves around the boys who are experiencing something special with a single strum of the strings and bang of the drum,” wrote Mary Beth McAndrews in her Paste review. Iwaisawa starts doing the same kind of rotoscoping (drawing over live-action footage for an expressionistic effect) as Waking Life or A Scanner Darkly—the kind of technique Linklater uses to create a “realistic unreality” in films that need their consciousness-expanding content to slap our eyes around with a little surrealist dreaminess.

Music might not give meaning to the lives of Kenji, Ota and Asakura, but it certainly makes them feel. Hands strumming a guitar, long hair swaying back and forth—the iconography of rock spills forth with fluid potency, speeding up the otherwise slow and static lives of its characters with an excitement never experienced elsewhere. It pushes them out of their comfort zone, onto picturesque piers and in front of crowds. Linklater’s rotoscoped heroes might be high on their own supply of philosophical musings or hallucinogens, but these teens are similarly transcendent as they take the stage. A multicolored, explosive climax is as sublime and transportative as Linklater’s most experimental—and it works best because the hilarious characters at its heart are as endearingly easygoing as the most mellow baseball bro in Everybody Wants Some!! What other kind of person would toot on a recorder in response to an enemy throwing hands? You see the three soar with the power of godly, macho, confident ‘70s-esque rock, so powerful a force that it redefines the group in the judgy eyes of everyone around them—even the mohawked rival gang looking to whip their asses.

On-Gaku feels of a piece with much of Linklater’s filmography, especially his earlier and more raw material in which he was closest to his subjects. His debut feature, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books, may be the most poetic comparison in its sheer dedication to the tedium and potential of the everyday. In fact, its very title goes back to what Iwaisawa was saying about his own debut: He had no money and no skill to make this movie in the traditional way, so he did it (and thus learned how to do it in the process) his own way. The resulting film does for a younger generation—simultaneously more nihilistic and optimistic than Linklater’s jaded Gen X amblers—what Linklater’s early works did as pieces of Austin-centric anthropology. And, like Linklater’s best, it has a grand old time in doing so.

Jacob Oller is Movies Editor at Paste Magazine. You can follow him on Twitter at @jacoboller.

For all the latest movie news, reviews, lists and features, follow @PasteMovies.