Does Chicago‘s Satire Still Work?

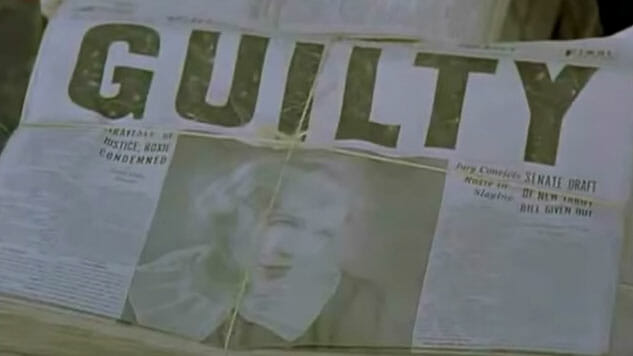

The leap from the blinding flash bulbs of journalists’ cumbersome cameras swarming outside of a prison—anxiously waiting to make a star, or a martyr, out of a murderess—to the ravenous helicopter cameras tracking a white Ford Bronco on the highway, also reframing someone already famous into a different kind of celebrity, is a fairly small one. Like all the best satire, Chicago’s truths grow more apparent, and aberrant, over time. The nine-decade-old satire of the thin line between fame, infamy and exploitation, originally penned by former journalist Maureen Dallas Watkins in 1926, has been adapted a litany of times, perhaps most famously by director Bob Fosse in 1975, with Gwen Verdon as Roxie Hart and Chita Rivera as Velma Kelly. Rob Marshall would then adapt it to the screen in 2002 for a post-OJ Simpson murder trial world, but the question of that particular adaptation as satire either speaks to the triumph of the previous versions of the text or the failure of our own culture to discern adoration and critique.

Fosse adapted Chicago as a musical, with John Kander and Fred Ebb writing music and lyrics, for Verdon, for whom acquiring the rights was a passion. Fosse’s work over the course of his career became increasingly sharply dark, staccato, his precision in movement (shoulder rolls, tips of a hat, fingers rigidly dancing on the back of a chair) not so much erotic as anti-erotic. What eroticism exists in the numbers that Liza Minnelli performs as Sally Bowles in Cabaret is intentionally deflated, made seedier—corrupt even. While Fosse had a particular kind of empathy, and a kind of understanding of the women characters he helped create, the baggage of his own past and damage infected those portrayals, often to the benefit of the work itself. That kind of trauma in art allowed Fosse to present a complexity about gender, sex and the world in which they exist that codified him as a provocative genius. (It was also, unfortunately, the thing that informed his abuse of power and his status as an art monster of sorts; something that All That Jazz kind of addresses and FX’s Fosse/Verdon does not dive deeper into any more than Jazz.)

Marshall’s problem-solving did not involve, so much, a radical approach to the material, but more of a fix for an audience that had grown fairly disenchanted with movie musicals. Even if Moulin Rouge! had been been a success, its stylization, particularly in relation to its notion of “romanticism,” allowed it to get a pass from audiences that were no longer accustomed to the singing out loud diegesis of classic movie musicals, like Oklahoma!, Singin’ in the Rain or the movie that effectively killed the big budget Hollywood movie musical, Hello, Dolly! Cabaret was, notably, a departure because the Kit Kat Club in which Sally Bowles sings feels like a netherworld, both existing and commenting on the world in which it exists. It is, not unlike other stages, prone to the logical fallacy that this stage is exempt from the political world that it is contained within, hence the abrupt absence of the Emcee (Joel Grey) and the long track of the reflective wall revealing Browncoats. Chicago’s fix was at once simple and contained a potential for nuance: Marshall’s framework was that the world of Chicago, all of its glittery numbers, were seen through the eyes of Roxie (Renée Zellweger). In scenarios where she is feeling anxiety or fear or distress, the world turns into a stage.