Every Christopher Nolan Movie, Ranked

A filmmaker concerned with time, with information, with magic tricks and reveals and all the things that go unnoticed when your attention is misdirected, Christopher Nolan has a reputation for making big movies that seem smarter than they actually are. Stereotypically, his fanboys love to seem that way too. But as we rank his movies, it becomes clear that Nolan’s greatness exists beyond this surface, in the details of his craft and the intersections of his ambitions.

As our Jesse Hassenger writes, Nolan is “prone to both methodically ascending his big, obvious building blocks and attempting to take wilder, more ambitious leaps.” That leads to massive blockbusters that ask more of an audience than most, and half-baked gestures towards weightier themes that those accustomed to more nuanced filmmaking may chafe against. His better movies find balance between these tendencies. His best play them against one another. But they all are consuming, heady, highly practical showcases for his style and emotional earnestness. Whether he’s reinventing what the superhero movie could be, supplying college dorm rooms with poster-ready fan-theory machines, or simply reveling in the technical possibilities afforded to him, Christopher Nolan’s movies offer an exciting element that so few mainstream films do: An artistic depth that rewards you the more you think about them.

Here is every movie by Christopher Nolan, ranked:

12. Following (1998)

If the title of Christopher Nolan’s Following were a gerund, it would describe the actions of the film’s young male protagonist (Jeremy Theobald), who, as a means of ridding his life of boredom, aimlessness and likely some other, unspecified feeling of ennui, decides to tail random (and, eventually, not so random) strangers through the streets of London. If interpreted as a noun, however, the title could be presciently referencing the massive body of admirers Nolan will accrue in subsequent years thanks to the directorial trademarks first introduced in his debut. Most prominent among these include a brooding antihero driven to action by an idée fixe and, even more iconically, non-linear storytelling whose temporal fragmentation turns plot into a puzzle to be solved. In the end, the coming-together of Nolan’s first conundrum satisfies but feels a tad shallow, not least because the non-linearity on display is pure surface, an exercise in audience manipulation that lacks any clear narrative or thematic justification. Whereas a film like (500) Days of Summer chops up linearity to evoke the erratic movement of memory, and Nolan’s own Memento (released in 2000, only two years after Following) explicitly orients its non-chronological structure vis-à-vis the amnesiac hero’s fractured sense of time, Following would have been more or less the same movie had its story been told straight. The only missing thing would’ve been the fleeting, primordial pleasure of seeing the narrative gaps, forcibly generated by Nolan’s slice-n-dice storytelling, filled in—of seeing the incomplete made whole. Shot on black-and-white 16mm and starring non-professional actors, Following exhibits the visual sensibilities of the French New Wave, but its spirit straddles Hitchcock and classical film noir. The likes of Double Indemnity and Out of the Past are evoked in the heavy shadows, the femme fatale archetype and the fact that the bulk of the movie is told in flashback. The Master of Suspense, on the other hand, surfaces in numerous other details: the Rope-esque duo of the dandyist male criminal (Alex Haw) and his partner, the sudden bursts of psychopathic violence, the way in which the driving plot point of fetishistic burglary thematizes voyeurism in tandem with the seductive transgression of invaded privacy and crossed boundaries. Nolan had his start with a sparse, stylish little movie meticulously constructed around the director’s cinephilia and his sense of narrative play. Though the Nolan of titanic epics has his merits, we would do well to remember his more impish side as well.–Jonah Jeng

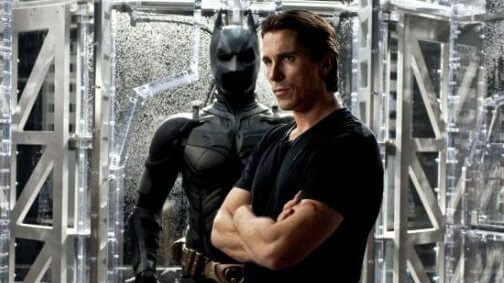

11. The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

At two hours and 44 minutes, The Dark Knight Rises is way too long … and way too short. Welcome to the temporal paradox that is the third, final and a bit overladen entry of Christopher Nolan’s tripartite take on the caped crusader. In the third film of his trilogy, Nolan brings his A game (and A team, for that matter) to bear in an attempt to at least match the billion-dollar-grossing, Heath Ledger-elevated The Dark Knight in tone, tenor and pace. But between multiple characters afflicted with “plotty mouth” and a need to have readers suspend disbelief early and (a bit too) often, this trilogy capper falls well short of the two films that preceded it. After all, nearly three hours may seem like a long time to maintain tension and viewer interest in anything not involving hobbits or the NFL, but it’s also all too short when you’re trying to juxtapose the slow burn of a hero’s psychological journey (and physical recovery) with a villain’s crisp, diabolical plan (and throwing in three to four additional character arcs for good measure). It’s at this intersection of hurry up and slow down that the film both bogs down and skips beats. It’s why 30 minutes more would have told a more convincing tale of Bruce Wayne, and 30 minutes less would have done wonders for the story of Batman’s battle with Bane. Still, though The Dark Knight Rises may have joined the long list of finales that did not measure up to what went immediately before, that doesn’t make it any easier of an act to follow.—Michael Burgin

10. Insomnia (2002)

Released squarely between Christopher Nolan’s introduction to the world as an intriguing British import with Memento and his ascension to box-office god with the revamped Batman trilogy, Insomnia is a film that often falls between the cracks. And that’s a shame. Taking its title and premise from a 1997 Norwegian thriller starring Stellan Skarsgard, the film casts Al Pacino in the central role of an insomnia-ailed police detective who travels to a remote Alaskan town to investigate the murder of a young teenage girl. His chief suspect is a true crime writer named Walter Finch (played, with surprising menace, by Robin Williams). Typically known for their gleefully over-the-top histrionics, both Pacino and Williams are refreshingly understated here, giving their scenes together a quiet, yet tense pulse.–Mark Rozeman

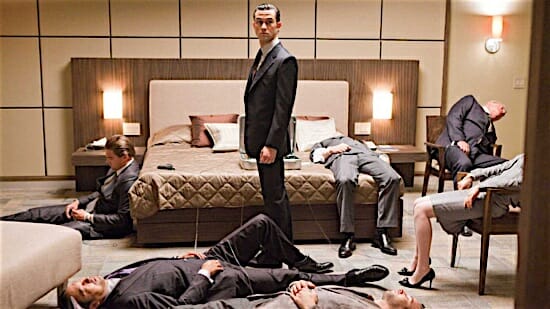

9. Tenet (2020)

A classic Christopher Nolan puzzle box, at first glance Tenet is a lot like Inception. The central conceit that powers it is both cerebral and requires copious on-screen exposition. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this. Nolan’s films always have at least one person trying to get their head around what exactly is going on, and it makes sense the audience would be as confused as the Protagonist (John David Washington), especially early on. Also, as with Inception, Tenet is basically a series of heists—smaller puzzle boxes within the larger one—which means while the viewer may not understand exactly what’s going on big picture, they will find the immediate action briskly paced and compellingly presented. Still, despite a compelling performance from Kenneth Branagh as antagonist Andrei Sator, the cerebral underpinnings and and even as the exact mechanics of this particular puzzle may demand more from the filmmaker than the audience, no amount of painstakingly crafted “time-inverted” action sequences nor Ludwig Göransson’s sweeping score can fill that hole occupied by a sympathetic main character, which Tenet lacks. None of this rests on Washington. Past Nolan protagonists like McConaughey (Interstellar), Pearce (Memento) and DiCaprio (Inception) not only had actual names, they had relatable motives and discernible emotional arcs. And though personal growth and emotional depth are hardly necessary ingredients in a spy thriller—just look at Bond, classic Bond—with so much else about Nolan’s script a mental exercise made real, some emotional stakes would be helpful to bring it alive. That might keep Tenet from the #1 slot on this year’s Best Sci-Fi list, but it shouldn’t keep lovers of the genre from seeing the only big budget science fiction to debut in theaters in 2020. —Michael Burgin

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-