Last week, news broke that Tomorrow Studios had inked a deal with Sunrise Inc. to co-produce a live-action television adaptation of Cowboy Bebop. The 1998 series, which originally aired on TV Tokyo before being rebroadcast on Cartoon Network’s late-night Adult Swim block, has gone on to become a perennial favorite among anime fans and a torch-bearing example in regard to the medium’s potential for sophistication and artistry. Tomorrow, a Los Angeles based production house partnered with ITV Studios, has been on something of a buying spree as of late, acquiring the rights to not only to a television adaptation of Bong Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer, but also the rights to John Ajvide Lindqvist’s Let the Right One In and Erik Axl Sund’s psychological horror series The Crow Girl. Though the series’ cast has yet to be announced, Chris Yost (Thor: The Dark World, Thor: Ragnarok) is currently slated to act as its lead writer.

Naturally, as is with any news of an American adaptation of a beloved foreign property, initial response to this announcement has ranged anywhere between “confused”and “livid.” With the recent critical fumble of Paramount and Dreamworks’ live-action Ghost in the Shell remake, as well as past examples of ingloriously tone-deaf adaptation such as Dragon Ball: Evolution, fans of the original Cowboy Bebop series have just cause to be apprehensive if not outright antagonistic towards an American studio handling the property.

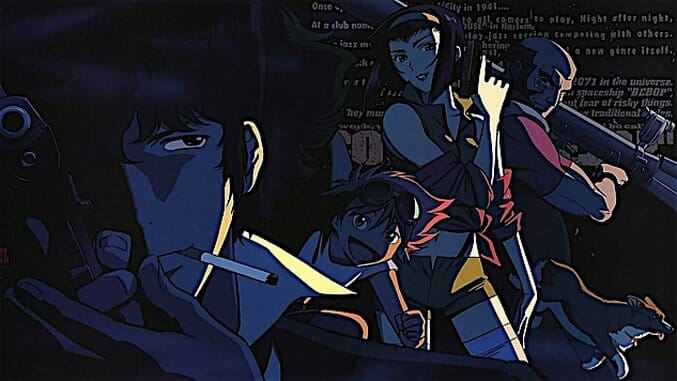

Set in the year 2071, Cowboy Bebop follows the stories of four bounty hunters who, through either serendipity or happenstance, team up to hunt down criminals and eke out a living on the fringes of space. The series is lauded for many things, among them its action and anachronistic neo noir aesthetic, but also its thematic underpinnings of existentialism, nostalgia and ennui. All of which make it a quintessential touchstone of pre-millennial fiction. Produced by Hajime Yatate (a collective pseudonym for the works of director Shinichiro Watanabe, screenwriter Keiko Nobumoto, character designer Toshihiro Kawamoto, mechanical designer Kimitoshi Yamane and composer Yoko Kanno, among others) the series is highly regarded as nothing short of sacrosanct among a generation of anime fans who witnessed the medium’s globalization around the turn of the century. With a successful 26-episode run capped off by an exemplary feature-length film, why dredge up a series that’s already well enough made its mark?

Perhaps the answer is as simple as, “Some things are inevitable.”

Cowboy Bebop, perhaps more than any other anime series to date, has always been a prime target for American adaptation. Despite having not explicitly been produced with the intent of appealing to a western audience (anime production was far more insular and domestically focused at that time), director Shinichiro Watanabe’s inspirations were always global. Initially commissioned and sponsored by Bandai’s toy division, Watanabe was given carte blanche to direct the series, “So long as there’s a spaceship in it.” Initially drawing from the freewheeling ensemble energy of Lupin III, Watanabe’s inspirations expanded outward and grew to encompass three of his biggest passions: music, cinema and western television. Cowboy Bebop draws heavily from the era of French New Wave film, in particular the works of Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Melville, as well as their spiritual disciples in the form of John Woo and Wong Kar-wai.

The French New Wave, or simply “Nouvelle Vague,” is in part seen as the origin point for a then-new paradigm in the essence of “cool” in the mid-twentieth century. The magnetic charisma and allure of Henri Serre, Jean-Pierre Léaud and Alain Delon’s performances would compel an entire generation of filmgoers, in particular Asian audiences, in the words of John Woo, “to cut [their] hair like Delon and start wearing shirts and black ties.” It is Delon who is especially of note here, with the lackadaisical melancholy of Cowboy Bebop’s protagonist Spike Spiegel tracing a direct line of inspiration to that of Delon’s turn as the roguish, laconic assassin Jef Costello in Melville’s Le Samourai. Each of Cowboy Bebop’s protagonists acts as a sort of composite of Hollywood/film noir archetypes. The aforementioned Spike is the rebelliousness of Delon and Marlon Brando channeled through the physicality and appearances of Bruce Lee and Yusaku Matsuda. Jet Black, Spike’s business partner and captain of the series’ namesake ship, is a modern turn of a classic rough-and-tumble gumshoe who actually managed to leave the force after simply “getting too tired and/or old for this shit.” Faye Valentine, the Bebop’s most persistent stowaway, is the genre’s requisite femme fatale—a leather-clad amnesiac-turned-seductress who separates simpletons and criminals alike from their ill-gotten gains. The crew’s final member Ed, or Edward Wong Hau Pepelu Tivrusky IV if you want to get honorific, is perhaps the show’s most inventive character type: a genius, genderqueer ingenue with a mischievous ebullient personality. And then there’s Ein, the lovable corgi, because why the hell not?

There are entire papers, nay, whole websites devoted to unpacking the thematic and referential density of Cowboy Bebop’s 26-episode run. From the show’s effusive dedication to mid-twentieth century jazz, funk and rock music, epitomized through the convention of naming episodes wholesale after famous tracks and the episodes as a whole titled as “sessions,” to Yoko Kanno’s iconic and inimitable score. Alien, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, 1966’s Django, Pierrot le Fou—it’s all there if you look closely enough. What this means in the case of Tomorrow Studios’ adaptation is that, in order to create a live-action installment that does justice to Cowboy Bebop, it would have to pay regards to the series’ antecedents. Furthermore, it wouldn’t hurt to consult with Yoko Kanno on the matter of the show’s music, not only considering that the original series music is so indelibly linked to core appeal, but that it would be a chance to introduce Kanno’s tremendous talent to a new generation of western television audiences. The potential, and perils, of such a creative undertaking are staggering. This new series could never hope to be live-action television’s equivalent to the 1998 masterpiece. That distinction would go to Firefly, Joss Whedon’s short-lived yet posthumously canonized sci-fi western. Like Firefly, Bebop did not even air in its entirety during the series’ initial run on TV Tokyo. Criticized for occupying an unfavorable time slot, as well as its uncharacteristically “Americanized” tone and subject matter, Bebop would only gain prominence after its airing on Adult Swim, becoming the first anime broadcast during that block and a flagship for the channel.

Instead of drawing these explicit comparisons, it serves us better to approach the concept of this new series as something of a reprise of the original, an improvisational interlude highlighting the original’s core appeal while adding something new and compelling into the mix. Maybe better portrayals of Vicious and Julia—two characters who, despite exerting enormous influence over Spike’s arc as central antagonist and love interest respectively, come across as paper-thin caricatures when compared to the series’ core cast. The most important thing to remember is that, although Cowboy Bebop is many things to many people, it is at its heart (perhaps to the surprise of some) a period piece, though not of any one explicit decade. Bebop is a time capsule of an aesthetic, a cinematic crock pot brimming with an eclectic gumbo of inspirations that manages to rise above any one referent and become entirely its own. In essence, the show is a true embodiment of its mission statement, “…And the work, which has become a genre unto itself, shall be called: Cowboy Bebop”

To be frank, it doesn’t inspire a whole lot of initial confidence to hear that a studio whose most recent claim to fame was John McNamara’s now-cancelled Aquarius, starring David Duchovny, has acquired the rights to one of if not arguably the most beloved anime series of the late 20th century. But then again, wasn’t Watanabe more-or-less unproven when he directed Cowboy Bebop, in spite of his work co-directing 1994’s Macross Plus with Shoji Kawamori? All I’m saying is, let’s save the vitriol until after we’ve seen some key visuals. I, for one, am as curious as I am cautiously optimistic to see if this live-action incarnation can rise anywhere close to the novelty and mettle of its predecessor. If not, at the very least it’ll make for a noble failure.

Let’s hear you play, kid.

Toussaint Egan is a culturally omnivorous writer who has written for several publications such as Kill Screen, Playboy, Mental Floss, and Paste. Give him a shout on Twitter.