Best of Criterion’s New Releases, April 2020

Each month, Paste brings you a look at the best new selections from the Criterion Collection. Much beloved by casual fans and cinephiles alike, Criterion has for over three decades presented special editions of important classic and contemporary films. You can explore the complete collection here.

In the meantime, because chances are you may be looking for something, anything, to discover, find all of our Criterion picks here, check out some of our favorite new releases from April, and, hey, since many of us have a lot more time on our hands, maybe sign up for Criterion’s Criterion Channel to stream many of the titles we talk about here.

Me and You and Everyone We Know Year: 2005

Year: 2005

Director: Miranda July

Stars: Miranda July, John Hawkes, Miles Thompson, Brandon Ratcliff, Carlie Westerman

Genre: Comedy, Drama

Rating: R

Runtime: 91 minutes

Calling Me and You and Everyone We Know, the first feature from Vermont-born interdisciplinary artist Miranda July, “punk,” as Sara Megheimer does in her essay for the Criterion Collection’s Blu-ray release of the film, feels generous. Punk is indeed about more than pierced noses and mohawks, raw musicianship and shitty production. It’s an all-encompassing aesthetic. That July would find inspiration in punk rock’s defining “I don’t give a fuck what you think about me or my sound” spirit makes sense: She didn’t fit into any predefined artistic mold in 2005, and still doesn’t today. Me and You and Everyone We Know is “punk” the way that the works of Sean Baker are “punk,” which is to say that the film isn’t defiant as much as it is specific to her vision as a filmmaker.

There’s no anarchy here. There’s no rebellion. There’s just painful molecular-level awkwardness imposed on characters so shamed by their wants and needs that spending time with them grows nearly intolerable by the end of the picture. But whether Me and You and Everyone We Know is punk or not doesn’t matter when it’s so many other things: twee, gentle, quirky, sweet to a point and, above all else, true to July’s artistic spirit. At least it gave us the reference point for one of the best Cards Against Humanity cards ever. —Andy Crump

The Cremator Year: 1969

Year: 1969

Director: Juraj Herz

Stars: Rudolf Hrušínský, Vlasta Chramostová, Jana Stehnová, Miloš Vogni?

Genre: Comedy, Drama

Rating: NR

Runtime: 100 minutes

The Czechoslovakian government banned Juraj Herz’s The Cremator right after its premiere in 1969 and kept it under wraps until the communist system’s house of cards tumbled down in 1989, so that means it has to be good. “Good” roughly translates in this case to “bizarre”: The Cremator is the story of a genially oppressive looney tune who runs a crematorium in 1930s Prague and also thinks cremating the dead equates with freeing their souls from the material realm. Put kindly, he’s eccentric. Put bluntly, he’s a dominating personality type whose work aligns him with the rising Nazi party, suffocating both prospective clients and his family with his pontificating nonsense. But Herz finds black humor in the syrupy mannerisms of his protagonist, Karel Kopfrkingl (Rudolf Hrušínský), whose fleshy dough ball of a visage overwhelms The Cremator’s frames for better and worse. Looking about his apartment for a wall on which to hang a new portrait, Kopfrkingl imagines himself, in a series of fast cuts, in several corners of the space seemingly at once, posing with the picture, feigning seriousness and reading as goofy. The Cremator, though, is anything but goofy. It’s grim. Obsessive belief in warped ideology tends to produce bleak outcomes, of course, and Herz’s film is as bleak as they come. —Andy Crump

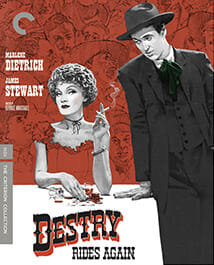

Destry Rides Again Year: 1939

Year: 1939

Director: George Marshall

Stars: James Stewart, Marlene Dietrich, Mischa Auer, Charles Winninger

Genre: Comedy, Drama

Rating: NR

Runtime: 94 minutes

Blazing Saddles obsessives: You owe it to yourself to watch Destry Rides Again. There are some obvious connections, like how in Blazing Saddles, Madeline Kahn seems to lift her sultry yet chronically fatigued German saloon entertainer pretty much directly from Marlene Dietrich’s Frenchy, a firecracker who can certainly hold her own in a barroom brawl. (Quite a progressive character for a 1930s Hollywood Western.) Then there’s director George Marshall’s light, slapstick-inflected touch with a Western 101 premise—new sheriff (Jimmy Stewart) rolls into a rowdy town to set it straight—which helped make Destry Rides Again a massive hit, as well as set a new tone, drawing a delicate line between parody and tense drama, for the genre without jeopardizing the audience’s grounded connection to his characters. (The fact that it revitalized Dietrich’s then-dead career is the cherry on top.) Look to the film’s many fight sequences, full of outrageous yet carefully choreographed chaos, and it’s hard not to see the scene in Blazing Saddles where we’re introduced to Rock Ridge. (All that’s missing is an old woman getting beat up while complaining, “Have you ever seen such cruelty?”) Marshall delivers an infectious atmosphere of fun, while Dietrich and Stewart employ their natural charms in service to some dynamite chemistry.

Criterion’s HD transfer on blu-ray captures this comedy’s lively black-and-white look while retaining a healthy amount of film grain. There are some spiffy new extras, like an interview about the film’s production from critic Imogen Sara Smith. The highlight is a condensed look at the life of Jimmy Stewart, care of his biographer, Donald Dewey. —Oktay Ege Kozak

Army of Shadows Year: 1969

Year: 1969

Director: Jean-Pierre Melville

Stars: Lino Ventura

Genre: Drama

Rating: NR

Runtime: 145 minutes

After France fell under the control of the Nazi war machine during the Second World War, pockets of resistance sprang up against Germany and the complicit Vichy government. Operating its campaigns in secret, the Resistance has become a bedrock of French national identity, coloring the perceptions of people who understand occupied France’s role in the war. Director Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1969 adaptation of the 1943 novel Army of Shadows is the stark, uncompromising answer to anybody’s attempt to romanticize the period. It argues with chillingly relatable humanity that fighting against a brutal empire and living daily with the fear of death doesn’t look or feel heroic.

Set about Paris and Lyons and occasionally London in a time when Nazi marching bands parade past the Arc de Triomphe, the film opens on Philippe (Lino Ventura) as he is brought into a prison camp. He whispers of the possibility of escape, but it’s not that kind of movie. Sitting in a pristine Nazi office awaiting questioning for what he must know of his Resistance cell, Philippe escapes in the least heroic manner imaginable, tricking a stormtrooper into letting his guard down for a moment and then stabbing him. The other man waiting with him promptly runs into a hail of gunfire while he sneaks out the other way.

A fugitive, Philippe joins up with a small and determined cell of Resistance members, trying to drum up support in England but mostly trying to stay one step ahead of the Gestapo’s vicious dragnet, all the while sure that it’ll close around him eventually. More than any other activity, Philippe and his comrades are concerned with either silencing traitors or trying to rescue (or more likely, mercifully kill) those from among their ranks who have fallen into the clutches of the Nazis. It never looks pretty. There’s plenty of derring-do and grizzled war-time determination, but even the moments of hitching a ride on a submarine or parachute dropping in the dark amidst enemy flak are tempered with humanizing, even absurd little details. Melville told one interviewer that he “avoided all realism” in the movie, seeking not to make a film about the French Resistance. What he made instead isn’t so much disillusioning as it is deeply empathetic. This is not a rah-rah war movie or a jingoistic call to arms. This is a story arguing that surviving danger, even in service of one’s countrymen, doesn’t ennoble anyone. —Kenneth Lowe

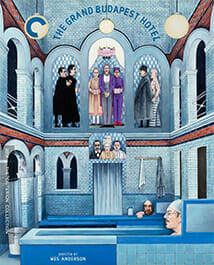

The Grand Budapest Hotel Year: 2014

Year: 2014

Director: Wes Anderson

Stars: Ralph Fiennes, Tony Revolori, F. Murray Abraham, Adrien Brody, Saoirse Ronan, Willem Dafoe, Jude Law, Harvey Keitel, Jeff Goldblum, Mathieu Amalric, Tilda Swinton, Bill Murray

Genre: Comedy

Rating: R

Runtime: 100 minutes

The Grand Budapest Hotel is not in Budapest. It’s in the former republic of Zubrowka, a mountainous European nation that seems to be a sister state of Lubitsch’s Flausenthurm (from The Smiling Lieutenant) or Marshovia (The Merry Widow). These fake nations are also likely in league with Cracked Nuts’ El Dorania and, most famously, Duck Soup’s Freedonia. All of these films were released between 1931 and 1934, and the main action in Wes Anderson’s homage takes place in 1932. Why this time period? After the mass deaths of the first world war, Twentieth Century trauma and loss affected everything familiar, so imaginations sought escape in untainted, made-up places. (Not quite utopias, these countries usually featured an uneasy mix of fallen royalty, impossible bureaucracy and wandering livestock.)

Anderson’s between-the-war setting then seems to refer to both world wars, the first in tone and the second in plot, as menacing soldiers in black shirts threaten our hero, Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), and his old world ways, as well as the stateless orphan, Zero (Tony Revolori). The film might be called a post-Marie Antoinette period piece in its rich and unorthodox approach to history as autobiography.

It’s been said that Gustave is a version of Anderson. And it’s true that in the introduction to M. Gustave, in which he zips through the hotel lobby barking orders left and right, he is very reminiscent, in Anderson’s work, of the American Express commercial in which Anderson plays a “director.” There he plays an idealized version of himself based on his heroes, most obviously Truffaut, since the commercial is an homage to Day for Night. But Anderson also seems to be modeling his persona here on old 16mm interviews with John Ford, Howard Hawks and the self-mythologized John Huston. “Making movies. How do you do it? What’s it like?” he asks in clipped and salty tones while wearing a safari suit.

That relationship to his influences—how and maybe even why he makes his work—is what this film is all about. It seems to be a culmination of his last six films, which involved self-reflexive storytelling with a display shelf of his influences. He used different aspect ratios once before, in The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, but nobody really noticed. With The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson has proven he is the inheritor of the 20th Century, or at least its messenger boy. —Miriam Bale