Danny Says

In his new documentary Danny Says, director Brendan Toller trots out one of the most tired of recent tropes in documentary cinema: cutesy animation to illustrate talking-heads interviews. In Toller’s film, that cutesy animation is courtesy of Emily Hubley, Johnny Woods and Matt Newman-Long, ranging from simple hand-drawn images on a blue background to elaborate stop-motion. As literal-minded as they can sometimes be, these sequences are, to be fair, visually inventive and alluring. Whatever the methods, though, the intent is the same throughout: to depict events in Danny Fields’ life that, one assumes, Toller didn’t have archival footage/still photos to cover.

Considering Toller’s subject, however, the stylistic cliché turns out to be necessary. For all the anecdotes he offers about his legendary life as a journalist, publicist and tastemaker during the heyday of the ’60s and ’70s American punk era, Danny Fields turns out to not be the most dynamic of interview subjects. Speaking in every featured interview in a near-monotone drawl—whether expressly for the film or through archival audio/video—Fields way he tells frankly takes some of the fun out of even his most colorful anecdotes.

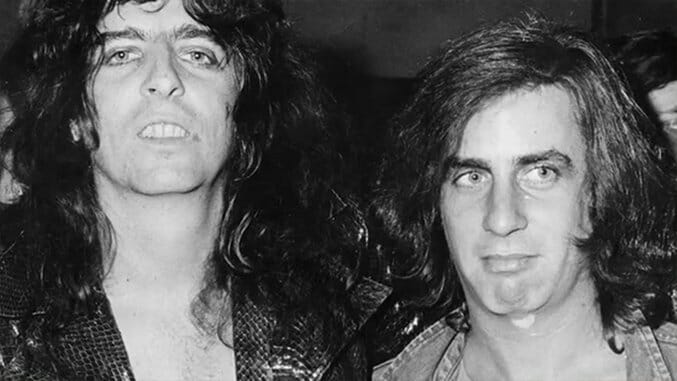

This is a shame, because Fields’ life is, in fact, quite an interesting one. He’s something of a real-life Leonard Zelig some degree, his “talent” is being in the right place at the right time with the right crowd, whether that means Andy Warhol’s Factory in the ’60s or the punk scene of the ’70s. That’s not to say that he wasn’t proactive about ensuring his own future success, though. For two decades he seems to have had a remarkable penchant for reinvention: from magazine editor (he was instrumental, however inadvertently, in bringing about the Beatles’ “more popular than Jesus” controversy), to publicist for Elektra Records (the company’s first), to self-appointed press agent for The Doors. Through it all, he remained tirelessly committed to, as he says, seeking out the “crazy people,” to the point that he basically ushered in the punk era when he discovered and promoted the Ramones.