David Cronenberg’s Crimes of the Past Point Towards His Future

David Cronenberg’s first feature, Stereo, released in 1969, is not an easy film to sit through. Despite its scant 63-minute runtime, it is experimental and entirely wordless, all plot conveyed through monotone narration. This commentary espouses convoluted pseudo-scientific jargon surrounding the telepathic abilities of a group of volunteers who aim to hone their powers through polymorphous sex. The wordlessness is due to the noisy, Arriflex 2C 35mm camera that Cronenberg used, and what could now be considered the very typically Cronenbergian preoccupations of the story are less of the point. Instead, Cronenberg wanted to emphasize the architectural surroundings of his subjects compared to the nonsensical narrative, with the now-familiar themes of mind v. body. v. an increasingly technologized world spoken out loud. Stereo was shot at the Andrews building of Scarborough College at the University of Toronto, where a young Cronenberg and his actor friends attended school. A newly erected building, with the emptiness of a structure entirely absent of life dwarfing the few people in the film, added to Cronenberg’s thesis on the relationship between humans and technology. In 2014, Cronenberg said “You have to think of architecture as an expression of technology.”

There has always been a perverse symbiosis between sexuality and technology in Cronenberg’s films, and this unique approach to sexuality—displayed in both Stereo and his 1970 follow-up, Crimes of the Future—caught the attention of Canadian film studio Cinépix Film Properties. Cinépix would go on to back his next two features, the ones that pushed the director into the mainstream: Shivers and Rabid. Crimes of the Future shares the same name as the director’s newest film, set to premiere on June 3. His early experimental works form a palpable pipeline which links the provocative horror director’s origins to his late career, leading all the way to a new interpretation (though not a remake) of Crimes of the Future.

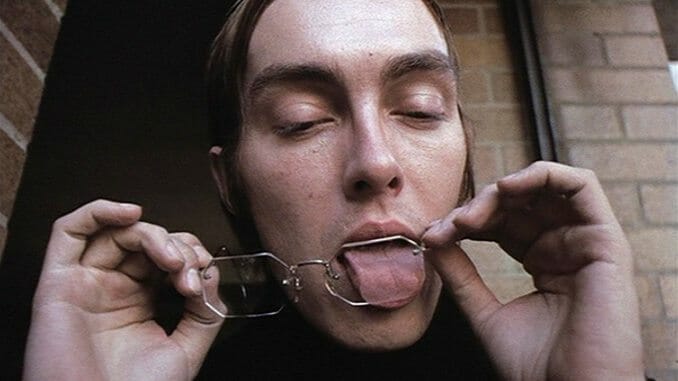

Like Stereo, the original Crimes of the Future was shot silent on the Arriflex (this time in color), had narrative commentary added afterwards and featured Cronenberg collaborator and friend Ronald Mlodzik (along with a handful of other players from Stereo) similarly oppressed by modern architecture. In a dystopian future, Adrian Tripod (Mlodzik) searches for his missing mentor, the unseen and insane dermatologist Antoine Rouge, who disappeared in the aftermath of a cosmetic-induced plague that wiped out all sexually mature women on the planet. Tripod then flits between groups of men struggling to adjust to this post-feminine world, ultimately finding a contingent of pedophiles who aim to force a young girl through puberty in order to impregnate her.

The challenging subject matter attributed to both films is more interesting in synopsis than in practice; on screen, both are very formal, narratively and performatively controlled, and, well, a bit dry. Interestingly, there is one overt aspect of Crimes of the Future (1970) that connects it to Crimes of the Future (2022), beyond the title: A brief scene in the former, in which a character carries around liquid-filled jars containing functionless organs that his body has begun to grow itself. A man’s way of giving birth in the absence of women. When a new organ is removed, another replaces it. In Crimes of the Future (2022), a performance artist couple (Viggo Mortensen and Lea Seydoux) travels the world showcasing the growth and removal of live organs in front of paying audiences. In both films, the characters are able to grow these new organs due to disease, and they inhabit a world ravaged by widespread catastrophe—in the new film, it’s climate change.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-