Hulu’s Nutcrackers Aims for Holiday Anarchy But Is Too Well Behaved to Earn It

Photos via Hulu

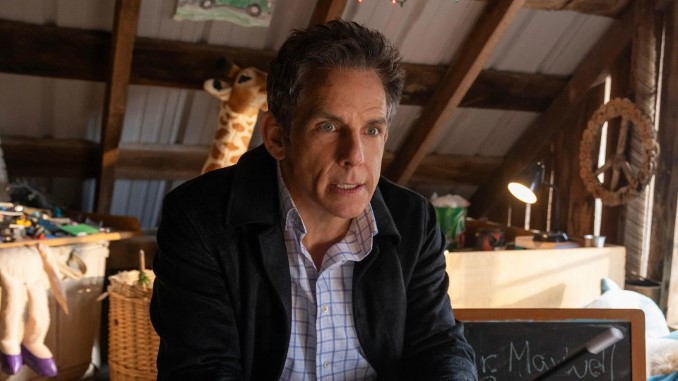

Having apparently come to the conclusion that he had butchered enough iconic horror franchises in the last decade to potentially tarnish his directorial brand, David Gordon Green looks to recalculate with a considerably lower-risk project in the form of Hulu’s new holiday dramedy Nutcrackers. This is a movie that smacks of a filmmaker simply trying to get back onto solid, even footing after some of the baffling decisions made in filmic disasters like Halloween Ends and The Exorcist: Believer. It perhaps unsurprisingly borrows a few units of coarse humor from the director’s stoner comedies of yore, but mostly takes on a more gentle dimension of heartwarming holiday apathy. Rather than pushing for anything genuinely prickly, challenging or truly heartfelt, Green and his collaborators–primarily screenwriter Leland Douglas and star Ben Stiller–are perfectly willing to punch the clock and fall back on the most well-worn and reheated Christmas movie pablum. Not that we should be particularly surprised.

Stiller, returned after a hiatus in lead acting roles since 2017’s Brad’s Status, steps into a role with obvious Uncle Buck allusions as Mike, a bigshot Chicago real estate agent who is roped into looking after his recently deceased sister’s four sons on a rural farmstead in the weeks leading up to Christmas. It effectively reverses the Uncle Buck dynamic, in fact: Whereas Buck was a blue collar grifter unaccustomed to the cushy confines and niceties of upper middle class suburbia, Mike is a polished urbanite (complete with Ferrari) who is immediately a fish out of water among the feral rural kids who have grown up in a world outside of cell reception and internet access. The miscalculation (the first of many) in the Uncle Buck comparison the film would so dearly like you to make, on the other hand, is that Buck was stepping in for what was supposed to be a last-minute pinch hitting assignment while the kids’ parents were away. Nutcrackers instead kills off both Mom and Dad, people that we never meet, which simultaneously limits the depth of the audience’s empathy and loads the entire cast with an aura of inescapable grief that it then has little interest in addressing and processing. The entire story is framed around this tragedy, but actually engaging with it meaningfully would be too much of a bummer, so the film instead just decides to half-ass it.

Although Mike is undoubtedly the film’s main protagonist, suddenly saddled with not only his sister’s children but also her debts and various other liabilities, it’s the kids who are the film’s real stars, which is a strength at times and a weakness at others. The “Kicklighter boys” are played by real-life siblings Atlas, Arlo, Ulysses and Homer Janson–sounds like their parents enjoy the Greek classics–and make their debut here as a quartet of unknowns, reportedly the children of a family friend of David Gordon Green’s. The film’s inspiration, in fact, seemingly came from Green seeing the boys in their natural element on the farm, resulting in Nutcrackers being written for them–the story of this gaggle of 8 to 13-year-old adolescents who have lost their parents, angling for the proverbial Christmas miracle. The screenplay positions them as supposed hellions, rambunctious troublemakers who can’t help but draw immediate comparison to the Herdman children of the recently adapted The Best Christmas Pageant Ever. The first time we see them in the film’s opening moments, they’re sneaking into an amusement park and inadvertently cause its tilt-a-whirl to self-destruct, like some oblique reference to the disastrous carousel in the closing moments of Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train. This bad behavior is meant to justify why it will supposedly be difficult for Mike to place the Kicklighter boys into a well-fitting foster home (particularly as a unit), but the problem is that they’re really never memorably crass, intentionally destructive or misbehaved enough to earn anyone’s ire as little hellraisers. You just can’t accept the idea that these sympathetic kids are supposedly undesirables in their rural town, where surely half the other local kids are ATV-driving, semiautomatic rifle-wielding punks of similar caliber.

Nevertheless, the kids (and their actors) really are charmingly strange in their own way–the relative inexperience of the performers comes across with a sort of wide-eyed and aloof naturalism, although the unfortunate trade-off is that half the time the kids aren’t always particularly intelligible. Both Mike and the audience don’t have much of an idea of what they’re going on about half of the time, and the two youngest brothers (twins?) are so undercharacterized that you’re unlikely to even recall their names. At the same time, though, there’s something intriguing about just watching those kids go about their business–they have the innocence and self-interested capriciousness of real children, tiny people who almost don’t seem to know they’re being filmed. Ben Stiller will be in the middle of trying to deliver a pep talk in the foreground of a scene, and you find yourself ignoring him to instead watch two of the kids randomly cavorting or fiddling with some object in the background. They’re entertaining to watch in exactly the same way that it’s entertaining to watch young boys on the playground who are totally absorbed in their own little worlds, blissfully shielded from the mounting responsibilities of plot or narrative. Who cares about Ben Stiller’s collapsing business deal back in Chicago; look at this cool stick I found!

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-