Hollywood Helper: Need Rich Biopic Material? We Know Where to Look.

White women who invent mops have nothing on these not-so-hidden figures.

As my colleague Shannon Houston wrote for Paste back in February, at the glacial rate Hollywood is putting out African-American stories, “I guess we’ll get their biopics after Hollywood is finished celebrating white women who created mops and such.”

There are endless ranks of heroes in this world who will never see their names in the large lights. How many mothers and fathers, doctors and teachers, and helpers and guardians hold up the world? And how few of them ever come to the attention of fame? Not everybody will have their story on Netflix. But as Houston points out, what is galling and indefensible is that there are already people of color who are celebrated—whose contribution to society and science is beyond question—and even they must wait in line behind the most incidental white celebrity. If our society loves everyone’s story equally, then why are there so many white heroes on celluloid, and so few of color?

If we look at these results, it is impossible to justify the lack of African-American protagonists in American cinema. We are forced, inevitably, logically, to wrestle with the fact that Hollywood has decreed a part of their audience doesn’t matter. Even from the standpoint of money, this is baffling. Since it was released on February 3, Get Out has made $175 million domestically another $77 million in foreign box office—for a movie made for $4.5 million, that’s a profit of about $247 million. There are countless other examples. We know the audience will watch movies made by, starring, and centered on African-Americans. We are forced to conclude that the public is not the problem. Hollywood is. They will give us stories of Secretariat and Seabiscuit before they even consider a Ralph Bunche movie.

The problem with Hollywood is one of concept. Their big universal love of narratives does not include African-American stories. Minds that dream of far-flung alien landscapes, and spreadsheets that can pay the ransom of ancient kingdoms for a summer night’s entertainment—all these great studios, which can photoshop scattered galaxies and score music for unseen dances, are unable to picture stories about black men and women, and this despite the ample evidence that films about African Americans yield excellent returns both in terms of critical and popular love. In other words, the audience is there. Hollywood is not.

Here’s a selection from an oral history of The Blues Brothers that’s stuck with me.

Or not. In the weeks preceding the movie’s theatrical-release date (June 20, 1980), Landis screens The Blues Brothers for major theater owners—“the guys with white belts and white shoes,” as he describes them.

The owners, who call themselves “exhibitors,” are Hollywood’s ultimate gatekeepers. They hold a movie’s fate in their hands. “Most of them said, ‘This is a black movie and white people won’t see it.’ Most of the prime houses wouldn’t book it.”

Landis cuts 20 minutes. In the meantime, another bomb explodes. “Lew calls me up to his office,” Landis says. “I go in there and he says, ‘John, do you know Ted Mann of Mann Theaters?’ ” Mann owns many of the country’s top movie houses, among them the Bruin and the National, both located in Westwood, a prosperous white neighborhood. “Lew says, ‘Ted, tell Mr. Landis what you just told me.’”

Then, Landis remembers, the conversation goes accordingly:

Mann: “Mr. Landis, we’re not booking The Blues Brothers in any of our national or general theaters. We have a theater in Compton where we’ll book it. But certainly not in Westwood.”

Landis: “Why won’t you book it in Westwood?”

Mann: “Because I don’t want any blacks in Westwood.”

Then, Landis says, Mann explained why whites won’t see The Blues Brothers: “Mainly because of the musical artists you have. Not only are they black. They are out of fashion.”

… The Blues Brothers makes $115 million, becoming one of Universal’s most enduring hits and by far its greatest farce.

Keep in mind this is a crew of executives talking about two white leads, during a time when those two actors were much bigger than they are now. Belushi was one of the biggest stars in the world. The objection was black music.

The list of white people who have gotten biopics does not make for inspiring reading. Even the pictures which theoretically center on African Americans are problematic. Radio is a notable example. The titular character, an African-American man, is ostensibly the focus of the story. However, I’d point out that Coach Jones—and not our man Radio—is the lead character of this film. Hollywood apparently finds it easier to do a biopic about a kindly man who cheered on a high school football team, then it does about the god-like Henry Highland Garnet. I would also put The Butler in this list—a movie which, like Radio, is not very good; a movie where the lead African-American character has a secondary, reactive role. (And let us not speak of The Blind Side.)

Why does Hollywood, even when the films are produced by African Americans, find it easier to cast black actors in roles which are supplemental? Hollywood’s thinking is woefully behind the times. But we’re here to help! Here is a list of African-American historical figures who you could make a movie about tomorrow.

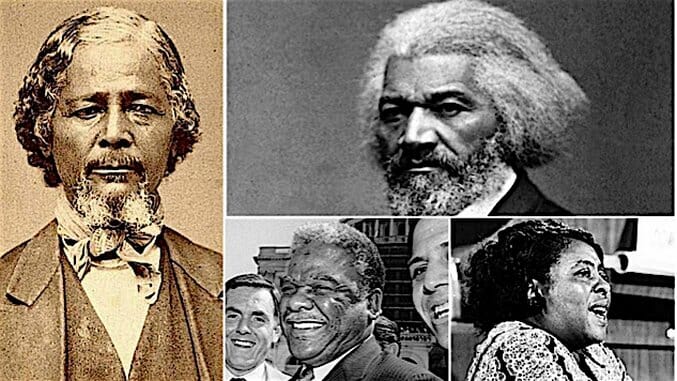

Frederick Douglass—The Statesman

By all rights, Frederick Douglass should have had several major motion pictures made about him. The movie has literally everything you’d want in a moving picture. Douglass even looks cool. He’s practically made to be an icon across all media. He becomes the spokesman for Black America when he is twenty. Twenty.

Here is a line from his autobiography: “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.” Doesn’t that cry out to be captured onscreen? Doesn’t that seem like a line for a movie promo? Far from being obligatory educational nutrition, Douglass’ autobiography is gripping reading: a slave escapes from cruel bondage, and through a series of extraordinary twists and turns, becomes the most powerful speaker of his day, an international celebrity, the most famous African American in the world, and a moral titan whose words echo down to the present age.

On July 5, 1852, he gives the speech “What to a slave is the 4th of July,” to the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in Rochester, New York, one of the great orations of our time: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” He does all this while being hunted by slavemasters during his early days, and bravely chastises the President while the man is still in office.

In 1889, he was still on the job, reminding the nation that “If the Republican party shall fail to carry out this purpose, God will raise up another party that will be faithful.” Unlike most male politicians of that day, he called for female suffrage. When they forced him to leave a train car because of his color, Douglass said, “They cannot degrade Frederick Douglass. The soul that is within me no man can degrade. I am not the one that is being degraded on account of this treatment, but those who are inflicting it upon me …” He was a true prophet, calling the nation to righteous account. This man should be on the quarter; at the very least, he should be in a movie. But we see him nowhere. Why is that?

Benjamin Pap Singleton—Western Hero

Benjamin Pap Singleton—Western Hero

Can you say epic Wild West story? Singleton was born into Tennessee slavery but made many attempts to escape. He became famous for building African-American villages in Civil War-era Kansas. He fled bondage in 1846 and became a daring abolitionist and civil rights champion. When the Union marched into Tennessee in 1862, he returned to his home state, but knew there could be no peace while whites held political and economic power. When Reconstruction perished, Singleton persuaded multitudes of black settlers, the Exodusters, to relocate to Kansas. He was a prophet of self-sufficiency for African Americans in the era when Jim Crow was invented.

In 1880, Singleton appeared before the Senate to defend the Exodusters. The racist bloc from the South wanted to discredit him and his cause. Can you imagine the showdown scene that would make in a movie?

On April 17, 1880, this is what Singleton told Congress:

QUESTION: Well, tell us all about it.

SINGLETON: These men would tell all their grievances to me in Tennessee—the sorrows of their heart. You know I was an undertaker there in Nashville, and worked in the shop. Well, actually, I would have to go and bury their fathers and mothers. You see we have the same heart and feelings as any other race and nation … I then went out to Kansas, and advised them all to go to Kansas; and, sir they are going to leave the Southern country. The Southern country is out of joint … The great God of glory has worked in me. I have had open air interviews with the living spirit of God for my people; and we are going to leave the South. We are going to leave it if there ain’t an alteration and signs of change. I am going to advise the people who left [Kansas] to go back.

Singleton stands as the best example of what could be: the rebirth of the Western as a genre to teach morality.

Harold Washington—The Mayor of Chicago

How do we have a world without a movie concerning the adventure, trials, and victory of Chicago’s first African-American Mayor? Washington’s reign in Chicago is a victory on two fronts: for the left against the machine, and for people of color against white hegemony. Washington, a lawyer and Congressman, came up in Bronzeville, the Midwestern hub of African-American culture for the first part of last century. He served overseas in segregated engineer corps, then returned to political life in Chicago.

About Chicago: it’s not a town like other towns. It belongs to a machine, the Cook County Democratic Party. From the old days, the machine owned Chicago politics. Owned it, and owned it wholly. There was zero chance of breaking its grip, although for years the people of the city tried. Nobody could make a dent, a lasting one. Until Washington. Washington is not the story of one man, but of how the forces of progress finally broke through in Chicago. Why does Chicago matter? Here’s how one book on Washington’s career, Gary Rivlin’s Fire on Prairie, explains it:

Chicago—the city whose name is synonymous with urban politics; the city of sharply divided ethnic and racial enclaves; the city whose police force shocked America during the 1968 Democratic convention and then the next year killed Black Panther leader Fred Hampton. As Martin Luther King, Jr., said when he traveled to Chicago in 1965 to turn his attention to the great urban centers of the North, “If we crack Chicago, then we crack the world.” Black empowerment “would take off like a prairie fire across the land.” In 1983 Chicago elected Harold Washington as the city’s first black mayor.

Washington represented an astounding coalition of the marginalized people of the city, all of the shattered fragments outside of the Democratic machine. It was an unlikely alliance, but it worked all the same. Washington’s victory is the tale of how Ed Vrdolyak and Jesse Jackson and Lu Palmer and countless others put together a fragile coalition that ruled for five years and changed the world. Miracles and wonders can abound, even in Chicago.

Fannie Lou Hamer—The Crusader

Hamer was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement, and that understates the matter. She did more in her fifty-nine years than most people do in a lifetime. If I may borrow from Stefon in a serious note, this story has got literally everything: the struggle for justice, dramatic battles, strife with the powerful. Hamer stood at the direct crossroads of social justice in the middle of the century. To read her history is to reinvent the Book of Acts. She was crucial to the struggle for Civil Rights in the South, during the maximally scary part of the battle, when very real death seemed to leer from every corner. Of her experiences, she said:

”I guess if I’d had any sense, I’d have been a little scared—but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

Hamer was in mortal peril most of her life, and suffered deprivation most of us cannot imagine. Hamer coined the sentence, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.” The child of poor sharecroppers, she knew hunger from an early age, and adult work from age thirteen, when she picked cotton alongside her family. After her marriage, she joined up with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, whose creed was civil disobedience and whose goal was the liberation of oppressed people.

In 1962, on a bus to Indianola, Miss., to register to vote, she began to sing spirituals, a practice for which she would become famous. For her, social justice was a religious crusade. She got fired by her employer later that day. She didn’t stop. Hamer was noticed by Bob Moses, and soon she was crossing the South, doing righteous work. In 1963, when traveling back from South Carolina with other activists, she was arrested by police. She and her friends were beaten, almost to death. She didn’t stop. She fought for voting rights. She organized the Freedom Summer in Mississippi. She represented the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which had to fight to be heard at the New Jersey Democratic Convention of 1964.

Eventually, Hamer and the rest of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party were invited to address the credentials committee. She shamed the President on national TV by recounting her ordeals. President Johnson, who was worried about having his spotlight stolen, called a press conference at the last minute. Johnson deployed Hubert Humphrey to talk with Hamer. When Humphrey explained that his political future might be in jeopardy, Hamer replied:

Do you mean to tell me that your position is more important than four hundred thousand black people’s lives? Senator Humphrey, I know lots of people in Mississippi who have lost their jobs trying to register to vote. I had to leave the plantation where I worked in Sunflower County, Miss. Now if you lose this job of Vice President because you do what is right, because you help the MFDP, everything will be all right. God will take care of you. But if you take [the nomination] this way, why, you will never be able to do any good for civil rights, for poor people, for peace, or any of those things you talk about. Senator Humphrey, I’m going to pray to Jesus for you.

Eventually, Hamer’s delegation was seated.

This nation is accounted the richest country in the world. But we are very poor indeed, if our movies—a place where we have no constraints—does not include black people. What does that say about us, and our poverty of spirit, of imagination? We cannot afford to let a generation of Americans grow up without knowing the full history of this country. That history includes African Americans, and their stories must be told.

Jason Rhode is watching everything, including you, right now.